Cartoon – Super Bowl Express Lane

https://mailchi.mp/2c6956b2ac0d/the-weekly-gist-january-29-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

Hardly a week goes by without a health system leader telling us about an initiative that’s been “put on hold because of COVID”.

The range of things delayed by the pandemic is wide, from major facility expansions to incremental changes in organizational structure and operational processes. But in general, there’s a growing list of action items—many of them critical—that health systems have been putting off. Across last year we heard that many had plans to return to those items in early 2021, once the COVID situation eased. But of course, the past two months have been the busiest of the pandemic so far, and now the challenge of vaccine rollout has been layered on top of the day-to-day task of maintaining care delivery amid persistently high levels of COVID hospitalizations.

With a protracted, uneven immunization campaign, and worrisome variants on the rise, there may yet be another surge of cases and hospitalizations in the spring, which will cause systems to further delay important projects. That’s not all bad news—surely some will realize that what seemed urgent pre-COVID is no longer necessary.

We’ve already had a few leaders tell us that COVID has forced a rethink of capital plans, with facility expansions likely scaled back in favor of faster investment in digital care delivery. But it’s worth remembering that COVID didn’t just cause hospital systems to delay or cancel non-emergent surgeries and procedures (to the tune of $20B last year). It’s forced these large, complex businesses into a state of suspended animation, and likely set back a significant number of needed operational improvements. It’ll take some time to catch up when this is all over.

Faced with the urgent need to protect nurses and other frontline workers, labor organizations are pushing hospitals to do more.

The unions representing the nation’s health care workers have emerged as increasingly powerful voices during the still-raging pandemic.

With more than 100,000 Americans hospitalized and many among their ranks infected, nurses and other health workers remain in a precarious frontline against the coronavirus and have turned again and again to unions for help.

“It’s so overwhelming. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen before,” said Erin McIntosh, a nurse at Riverside Community Hospital in Southern California, a part of the country that has been among the hardest hit by a surge in cases. “Every day I’m waist-deep in death and dying.”

In her hospital’s intensive care unit, Mrs. McIntosh said, nurses have sometimes cared for twice as many patients. “We’re being told to take on more than we safely can handle.”

Her union, the Service Employees International Union, and another union, National Nurses United, which has a powerful presence in California, have pushed back against the state’s decision to let hospitals assign nurses more patients during the crisis.

HCA Healthcare, the for-profit hospital chain that owns Riverside, responded that it had recruited additional nurses and was keeping its employees safe.

Health care workers say they have been bitterly disappointed by their employers’ and government agencies’ response to the pandemic. Dire staff shortages, inadequate and persistent supplies of protective equipment, limited testing for the virus and pressure to work even if they might be sick have left many workers turning to the unions as their only ally. The virus has claimed the lives of more than 3,300 health care workers nationwide, according to one count.

“We wouldn’t be alive today if we didn’t have the union,” said Elizabeth Lalasz, a Chicago public hospital nurse and steward for National Nurses United. The country’s largest union of registered nurses, representing more than 170,000 nationwide, National Nurses was among the first to criticize hospitals’ lack of preparation and call for more protective equipment, like N95 masks.

Despite the decades-long decline in the labor movement and the small numbers of unionized nurses, labor officials have seized on the pandemic fallout to organize new chapters and pursue contract talks for better conditions and benefits. National Nurses organized seven new bargaining units last year, compared to four in 2019. The S.E.I.U. also says it has seen an uptick in interest.

Nurses across the country from various unions have participated in dozens of strikes and protests. National Nurses held a “day of action” on Wednesday with demonstrations in more than a dozen states and Washington, D.C., as it starts negotiations at hospitals owned by big systems like HCA, Sutter Health and CommonSpirit Health.

Hospitals claim the unions are playing politics during a public health emergency and say they have no choice but to ask more of their workers. “We are in a moment of crisis that we’ve never seen before, and we need flexibility to care for patients,” said Jan Emerson-Shea, a spokeswoman for the California Hospital Association.

At the University of Illinois Hospital in Chicago, the deaths of two nurses from the virus helped galvanize employees to strike for the first time last fall, said Paul Pater, an emergency room nurse and union official with the Illinois Nurses Association. “People really took that to heart, and it really fomented a lot of disdain for the current administration at the hospital.”

In their most recent contract, nurses there won provisions ensuring the hospital would hire more staff and keep sufficient supplies of protective equipment, Mr. Pater said. “We’ve been able to make, honestly, just huge strides in protecting our people.”

The hospital did not respond to requests for comment.

Some nurses remain highly skeptical of the unions’ efforts, and even those who favor organizing acknowledge there are serious limits to what they can accomplish. “I’m not sure that the union is enough, because it can only take us so far” since staffing conditions remain overwhelming, said Mrs. McIntosh, the Riverside nurse.

Many health care workers view vaccines as the beginning of the end of the pandemic. But large numbers — especially those who work in nursing homes and outside hospitals, who tend to have higher rates of vaccine hesitancy — are refusing to be immunized. During a crisis that disproportionately threatens health care workers of color, one recent analysis found that they are getting vaccinations at rates far below those of their white colleagues.

The unions find themselves treading a fine line between encouraging their members to get vaccinated and protecting them against policies that would force them to do so.

“There are still unanswered questions,” said Karine Raymond, a nurse at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx and a New York State Nurses Association official. “The union believes that all nurses should seriously consider being vaccinated,” said Ms. Raymond, who would not say whether she personally would accept the vaccine. “But, again, it’s the individual’s choice.”

The nurses and their unions do want to keep pressuring employers to safeguard workers and patients. “Just because a vaccine is rolling out doesn’t mean that we can let up on other important protections,” said Michelle Mahon, a National Nurses United official, during a Facebook Live event last month.

The past year has created conditions ripe for organizing to address longstanding issues like inadequate wages, benefits and staffing, a problem exacerbated by health care workers falling ill, burning out or retiring early for fear of getting sick. The unions “have successfully been able to use the pandemic to rebrand those same conflicts as very urgent safety concerns,” said Jennifer Stewart, a senior vice president at Gist Healthcare, a consulting firm that advises hospitals.

They have also shifted many nurses’ view of their employers, she said. “The perceptions and the experiences are being crystallized and starting to be viewed through a certain lens. And I think that lens is very favorable to unions.”

At Mission Hospital in Asheville, N.C., safety concerns created by the pandemic added urgency to the nurses’ push to join forces with National Nurses United.

Some questioned the union’s ability to deliver better working conditions and raised concerns about the union creating divisions within the hospital. A group of 25 Mission nurses signed a letter before the vote saying “an outside third party, like the N.N.U., is not the solution.”

But last September, 70 percent of nurses approved the union, one of the largest wins at a hospital in the South in decades. Susan Fischer, a Mission nurse who helped lead the organizing drive, called National Nurses United “instrumental in helping us find our voice.”

She said the union was already proving its worth, pushing management in bargaining talks this month to provide better access to protective equipment and to assign nurses fewer patients.

In a statement, HCA, which owns Mission Hospital, said its highest priority was to protect workers and that the unions were “exploiting the situation in an attempt to gain publicity and organize new dues-paying members.”

In addition to staging protests and strikes, unions have defended workers who are speaking up against their employers. Some unions have sued hospitals, including one lawsuit against Riverside by the S.E.I.U. Similar cases have been dismissed in court, and HCA called the Riverside suit a publicity stunt.

Industry executives say the unions are unfairly blaming hospitals for the horrors of the pandemic. While some had difficulty providing protective equipment early on, hospitals have done their best to follow government guidelines and to protect workers, said Chip Kahn, the president of the Federation of American Hospitals, which represents for-profit hospitals.

Mr. Kahn said the unions were leveraging the crisis to achieve their agenda of organizing workers. “They’ll push whatever pressure points they can to try to force their way into hospitals, because that’s what they do.”

About 17 percent of nurses and 12 percent of other U.S. health care workers are covered by a union, according to an analysis of government data, and rates of union coverage have remained largely unchanged during the pandemic. The share of hospital workers with union representation has declined from above 22 percent in 1983 to below 15 percent in 2018, reflecting a decades-long decline in organized labor.

Some unions, including the outspoken National Nurses, have often seemed to occupy the fringes of the labor movement. For years it was better known for advocating proposals like Medicare for All, which would replace private insurance with government-run health care, and for enthusiastically backing Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont for president.

The pandemic, and the union’s decision to endorse Joseph R. Biden Jr. after Senator Sanders left the race last year, have tempered that reputation. Mission nurses said that politics was not part of the allure of National Nurses United. “Of all the unions we could’ve gone to, they had the best track record,” Ms. Fischer said.

The Biden presidency may give the unions an opportunity to flex their newfound muscle. Mary Kay Henry, the international president of the S.E.I.U., was among the labor leaders who met virtually with Mr. Biden last year.

“In my 40 years of organizing health care workers, I have never experienced a time when people are more willing to take risks and join together to take collective action,” Ms. Henry said. “That’s a sea change.”

https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/pediatrician-shot-and-killed-medical-office-austin

Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Ct.) is reintroducing a bill to help curb workplace violence in the healthcare sector to the 117th Congress next week.

In the latest incidence of workplace violence within the healthcare industry, a 43-year old female doctor was shot and killed by another physician at Children’s Medical Group in Austin, Texas on Tuesday afternoon.

Pediatrician Dr. Katherine Lindley Dodson, 43, died from a gunshot wound that Austin police believe was inflicted by Dr. Bharat Narumanchi, 43. Narumanchi died from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound, according to the police report. No motive was given for the attack.

When Austin Police SWAT officers made entry to the medical office building, they found the bodies of Drs. Dodson and Narumanchi inside.

Narumanchi did not work at Children’s Medical Group, but had been there a week earlier to apply for a volunteer position that he reportedly did not get. He was a pediatrician who had been recently diagnosed with terminal cancer, according to the police report.

Other than the visit to the office the week before, there did not appear to be any relation or other contact between Dr. Dodson and Dr. Narumanchi, police said.

In the 911 call, Austin police received a report that a male subject had entered the medical building with a gun and was holding hostages inside. As the incident began to unfold, it was learned that several hostages were being held. Several hostages initially escaped and others were later allowed to leave with the exception of Dr. Dodson.

Hostages told officers that Narumanchi was armed with a pistol and what appeared to be a shotgun and had two duffel bags.

Hostage negotiators arrived on scene and attempted to make contact with Dr. Narumanchi, to no avail, police said. After several attempts, it was decided to make entry into the building. It appeared that Dr. Narumanchi shot himself after shooting Dr. Dodson. The case is under investigation.

WHY THIS MATTERS

Workplace violence in healthcare is an ongoing issue, and the loss of Dodson is particularly tragic.

In a 2015 report the Occupational Safety and Health Administration stated that “healthcare and social assistance workers experienced 7.8 cases of serious workplace violence injuries per 10,000 full-time equivalents in 2013. Other large sectors such as construction, manufacturing, and retail all had fewer than two cases per 10,000 FTEs.”

Another report released by the American Hospital Association called the 2020 Environmental Scan, showed the rate of intentional injuries by others in 2017 to be 9.1 per 10,000 for healthcare and social assistance workers and 1.9 per 10,000 for all private industry.

One statistic that stands out is that nearly half of ER physicians said they’ve been physically assaulted at work and 71% have personally witnessed others being assaulted during their shifts. Since the most recent data is from 2017, the effect of COVID-19 is not included in these figures.

Most incidents of physical and verbal assaults are from patients to staff, according to National Nurses United head Michelle Mahon, assistant director of nursing practice for the professional association of registered nurses.

The issue has been exacerbated by the challenges of COVID-19, according to Mahon, who has said much of it could be prevented by ending staffing shortages.

EFFORTS

Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Ct.) is reintroducing a bill to curb workplace violence in the healthcare sector to the 117th Congress next week, according to information released by his office.

HR 1309, the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act proposed by Courtney, was passed in the House in 2019 after seven years of effort. It did not pass the Senate.

“Joe is confident about our prospects headed into this year,” his spokesman said.

National Nurses United supports the legislation that would create federal prevention standards not only for hospitals, but also for facilities such as Veterans’ Affairs, the Indian Health Service and home-based hospice. The law would require OSHA to develop workplace-violence-prevention standards that would include, among other mandates, that IV poles be stationary so they’re not able to be used as weapons.

The bill directs OSHA to issue new standards requiring healthcare and social service employers to write and implement a workplace-violence-prevention plan to prevent and protect employees from violent incidents and assaults at work.

Taking money hastily can create more problems than it solves if the additional resources aren’t tethered to need.

Taking a paycheck protection program (PPP) loan or other federally backed assistance to get through the pandemic will make your problem worse if you don’t have a realistic plan for the money, a former business owner convicted of federal loan fraud says in a White Collar Week podcast.

Jeff Grant, whose 20-person law firm was struggling when the federal government made emergency loans available after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, said he rushed to get the money without thinking through how best to use it. The result was a 13-month jail stint.

“It was raw desperation,” said Grant, who today focuses on helping other white collar criminals navigate a post-crime life. “At that point I was losing my business. I would have done anything for any gasp of air to try to save my business.”

Grant applied for a $250,000 loan under the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program, a resource that, along with the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), the federal government has once more made available, this time for pandemic-hit businesses.

To increase his chances of getting the money, he said on his application that his business was located across the street from Ground Zero in Manhattan, when it wasn’t — a form of wire fraud — and he used the money to pay off his personal debt — a form of money laundering, because the program’s debt covenants restricted the money for use only in the business.

“I had run up [my credit card debt] in the months prior [to 9/11], trying to save my business,” he said. “I was paying 24% interest on the credit cards. The EIDL loan was about 3%. It seemed to make sense: replace the 24% money with 3% money.”

For two years afterward, Grant said, he had no idea he was being investigated.

“Risk of an audit never entered my mind,” he said. “It was immediately after 9/11: a huge problem for the nation. I was just this little guy who was never going to have to account for anything.”

In addition to his business struggles, Grant was wrestling with personal problems that had jeopardized his law license. Facts emerging from bar association proceedings related to his practice may have led the government to investigate him, he said.

“I just got a phone call from two federal agents who told me there was a warrant out for my arrest,” he said.

Rather than fight the charges, he admitted his crime.

“Just like a business decision, you work from the end-result back,” he said. “I knew I had done something wrong. I wanted to pay for my crime. I made full restitution. A lot of people spend a lot of time and money trying to wriggle out of it, but we’re in a world where over 95% of criminal prosecutions result in plea bargains. There are virtually no trials. The government gives you a disincentive to defend yourself at trial and an incentive to resolve it quickly.”

Against the pandemic backdrop, Grant said, the kind of fraud he committed after 9/11 is probably much greater today, with hundreds of billions of federal loan funds available to struggling businesses, essentially on an honor system, since applicants simply check a box to certify their eligibility.

“One of my concerns is, people are just kind of wading in [to these programs],” he said.

Unlike EIDL loans, PPP loans don’t have to be paid back if the proceeds are used for eligible purposes, like payroll and operating expenses.

The government is making almost $300 billion in PPP assistance available under the latest funding round, enacted in December. Applications close at the end of the first quarter. Prior to this latest round, the program had made some $500 billion available, so more than $800 billion could be circulating by the end of the first quarter.

Grant advises against using the funds, even though they’re easy to access, to shore up a business that was either struggling before the pandemic or doesn’t have a realistic plan for getting through it, because the cash infusion can’t solve a systemic problem.

“You fall prey to magical thinking,” he said. “Money usually exacerbates problems without a good plan.”

He later worked with a nonprofit that, to attract customers, charged less than it recouped to provide services. As a result, the more services it provided, the more money it lost. It took out a $1 million state grant.

“Without fixing the business model, it blew through the $1 million in 18 months,” he said.

https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/bidens-most-ambitious-health-policy-a-public-option-plan/593342/

“It could fundamentally change how healthcare is priced in the U.S.,” said Cynthia Cox, vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

President-elect Joe Biden will seek to bolster the Affordable Care Act after his predecessor chipped away at the signature legislation, but he also has grander legislative priorities of his own for the health sector.

His most ambitious plan is to create a so-called public option plan, available to all Americans to purchase even if they already have coverage through their employers. It holds the potential to alter how millions get healthcare and put pressure on prices, experts told Healthcare Dive.

“It could fundamentally change how healthcare is priced in the U.S.,” Cynthia Cox, vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, told Healthcare Dive.

Still, even with control of Congress and the White House, the plan may take a backseat as the pandemic continues to sicken and kill a record number of people. And while the idea has drawn more support among Democrats in recent years, powerful interests like private insurers and providers will push back against the proposal, while some progressives have their eye on the more ambitious Medicare for All.

Simply put, a public option plan would give consumers a government-run choice for insurance, a market that can be tightly consolidated, leaving consumers with few carriers to choose from, especially in certain regions of the country.

“If your insurance company isn’t doing right by you, you should have another, better choice,” Biden has touted via his website.

Biden’s proposal allows anyone to buy a public option plan, even those now with employer plans. It is not limited to those only those on the exchanges, or consumers without employer plans.

Biden has said a public option plan will lower prices for patients because the government would be negotiating lower prices with healthcare providers. That theory relies on providers accepting these lower rates and electing to be in-network with the public plan.

The public option plan would reimburse providers less than typical commercial plans, which tend to pay the highest rates to providers for services compared to other government programs such as Medicaid and Medicare.

Ultimately, it is a more direct way to regulate healthcare prices in the U.S., Cox said.

As such, it will face fierce opposition from providers who typically treasure commercial insurance over other government plans as it tends to generate less revenue for hospitals and payers who see the option as competition.

A public option plan was included in early drafts during the construction of the ACA, though at the time it was limited to those without employer coverage. The idea gained support because policymakers were unsure how many private plans would sell plans on exchange. Plus, at the time, the idea was that it would offer premium pricing pressure and more choices in areas that potentially did not attract any on-exchange carriers.

In 2013, the Congressional Budget Office scrutinized the impact of adding a public plan to the exchanges. At the time, CBO’s estimates expected premiums to be lower than private plans by 7% and 8% on average. And CBO estimates showed it would reduce the federal deficit in a few ways, mainly through a decrease in subsidies as consumers opted for the public plan.

In the end, though, the idea was nixed to gain backing from moderate Democrats as Republicans villified it as a government takeover of healthcare.

While the public option was called too far left at the time of the ACA, it now may not be progressive enough for those in the liberal wing of the party, as ideas like Medicare for All have become more mainstream.

The shock of the COVID-19 pandemic may hasten calls for a bigger revamp, having laid bare the deep inequities in the nation’s healthcare system. Both death and infection rates are higher for people of color compared with their White counterparts.

At the same time, millions have likely lost insurance coverage as the economic upheaval caused by the pandemic resulted in historic job losses. Many Americans receive health coverage through work.

Earlier periods of upheaval paved the way for bold social programs such as those that followed the Great Depression via President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Prior to the pandemic, a public option was seen as more palatable for some than a “Medicare for All” option, a favored policy among the more progressive wing of the Democratic party. It was a heavily debated topic during the Democratic primary, during which Biden cautioned that such a plan would mean eliminating the ACA, a signature policy he helped enact as vice president.

A public option plan, while an ambitious measure, is not as industry-altering as Medicare for All, which would force Americans onto a single system and eliminate the private insurance market. A wing of the party’s progressive group continues to advocate for Medicare for All.

The Democrats currently have a 10-vote margin in the House, and an even slimmer margin in the Senate with Vice President-elect Kamala Harris serving as the tiebreaker.

Some had suggested those farther left in the party should withhold their votes for Nancy Pelosi as speaker of the House in exchange for securing a floor vote on Medicare for All. Pelosi ultimately retained her speakership position.

But Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., batted down such ideas as premature on Twitter due to the lack of Democratic votes to pull off such a move successfully.

“So you issue threats, hold your vote, and lose. Then what?” Ocasio-Cortez tweeted on Dec. 11.

Even with Democrats in control of Congress and the White House, don’t expect any sweeping healthcare legislative changes like Medicare for All, experts say.

The margins are so slim in the Senate it leaves one avenue to pass legislation: through so-called budget reconciliation. That avenue comes with complicated rules, generally limiting the kind of bills that can be passed to those with an impact on revenue, spending or deficits.

Given that hurdle alone, industry analysts don’t expect a public plan to pass through Congress, instead pointing to more incremental changes, which eases market fears of broad changes.

Plus, the pandemic will be absorbing most of the attention as the 46th president tries to stamp out the pandemic.

“Not to be overly simplistic, but I don’t think healthcare is on the front page of priorities,” David Windley, an analyst with Jefferies, said, pointing to Biden’s transition website, which does not call out other healthcare policy goals aside from tackling the pandemic.

It sets the table for a unique first term, Andy Slavitt, former CMS acting administrator under President Barack Obama, said. Slavitt will serve as a senior adviser to Biden’s COVID-19 response.

“For the first time in a long time, healthcare will not be a big first-term agenda item for the Congress,” Slavitt said during a healthcare conference last week. He expects Biden to focus on building back the ACA through administrative action and rule making as opposed to legislative battles in Congress.

“I don’t think Biden is looking to pick big divisive fights to the extent that healthcare looks like a big divisive fight. It doesn’t strike me that that’s where he wants to be,” Slavitt said.

Riot at U.S. Capitol prompted review of campaign contributions.

The American Hospital Association (AHA) has suspended contributions to legislators who voted against accepting the results of the Electoral College, the organization said in a statement.

The group did not provide details on exactly which legislators would now be cut off from AHA funding. As of Jan. 18, the association had not returned a request for comment from MedPage Today.

A total of 147 GOP members of Congress voted to overturn the presidential election results: 139 in the House and eight in the Senate.

In the statement, AHA called the January 6 events at the Capitol an “assault on our democracy,” and said it immediately launched a review of its donation practices to “ensure they are guided by our Association’s vision and mission, as well as the democratic values we share as a nation.”

AHA’s board of trustees decides on its political contributions after consulting with the steering committee of its Political Action Committee, along with state hospital association partners and hospital and health system leaders from lawmakers’ states and districts, the organization said.

“Hospitals and health systems have a special role to play as community leaders, healers, and caregivers for our patients and the wider communities we serve,” AHA said in the statement.

In a Jan. 7 blog post, AHA President and CEO Rick Pollack wrote that “peaceful protest is a cherished right and hallmark of our democracy, but vandalism, violence and mob rule have always been out of bounds, and need to stay that way.”

“Throughout our nation’s history, Americans have taken pride in the peaceful transfer of power at the highest level,” Pollack wrote. “It’s part of our precious heritage and distinguishes us from so many other nations of the world. But that gap seems to have narrowed this week and should concern all of us.”

Pollack and AHA called on the country to come together and begin the healing process, particularly as the nation’s COVID-19 crisis worsens.

“With so many critical issues and challenges facing our country, including putting an end to the COVID-19 pandemic and improving our health care system, we must come together now,” Pollack stated.

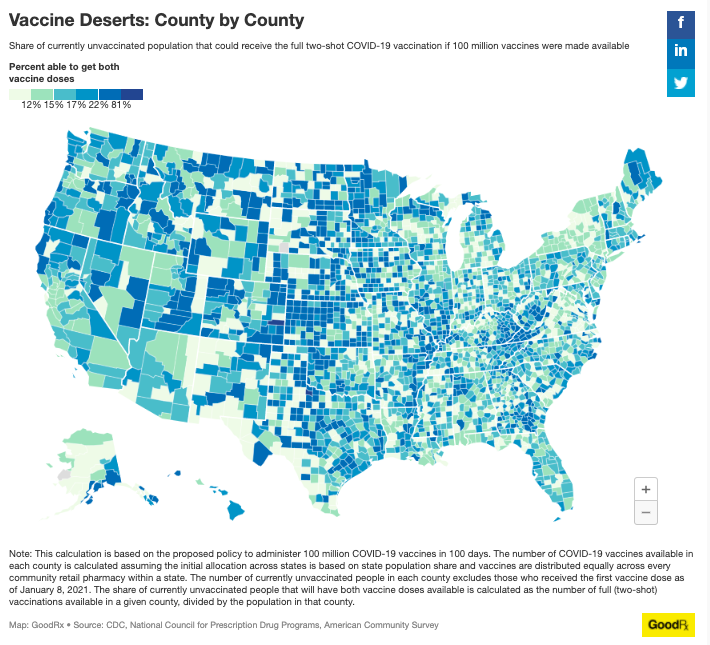

Millions of Americans who live in “pharmacy deserts” could have extra trouble accessing coronavirus vaccines quickly, according to a new analysis by GoodRx.

Why it matters: Places without nearby pharmacies, or with a large population-to-pharmacy ratio, may need to rely on mass vaccination sites or other measures to avoid falling behind.

The big picture: Pharmacies will play a huge role in the vaccine rollout, especially as shots become more available to the general population.

By the numbers: The incoming Biden administration has set a goal of vaccinating 100 million people in 100 days, or about 16% of the unvaccinated U.S. population, per GoodRx.

Dare we say it: The window for bipartisan work on drug pricing reform may be closed.

Sen. Ron Wyden, top Democrat on the powerful Senate Finance Committee, is focusing on a wish-list item for Democrats but poison pill for the GOP: eliminating a ban on the federal government using its negotiating power to directly force lower drug prices under Medicare.

“I think we’ve got to take bold action on prescription drug prices,” Wyden (Ore.) told reporters yesterday. “We’re going to be looking at all the tools to get this done.”

President Trump made lowering prescription drug prices a major promise during his campaigns. But despite some efforts, there has been major pushback from Capitol Hill and the pharmaceutical industry and not much has actually been accomplished.

Ten House Republicans joined Democrats yesterday to impeach President Trump a second time, amid near-chaos in the chamber and uncertainty about where Trump’s exit leaves the GOP, my colleagues reported.

“Democrats and Republicans exchanged accusations and name-calling throughout the day, while Trump loyalists were livid at fellow Republicans who broke ranks — especially [Rep. Liz] Cheney — leaving the party’s leadership shaken,” Mike DeBonis and Paul Kane write.

Focusing on direct negotiation, as Wyden urged yesterday, would cut Republicans out of the picture.

Back in 2019, Wyden tried very hard to keep Republicans on board such an effort, as he pushed for a limited, bipartisan bill co-written with Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa). That measure would have capped out-of-pocket costs for Medicare enrollees and required some rebates from drugmakers. But after passing in committee, the measure languished as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) refused to bring it to the floor.

It’s possible to imagine Democrats getting 60 votes to pass such an effort, now that they’ll control the Senate. After all, a half-dozen Finance Committee Republicans voted for it.

But in remarks slamming McConnell, Wyden yesterday said the majority leader proved his ultimate unwillingness to enact any significant drug pricing reforms under heavy pressure from the pharmaceutical industry.

Democrats, Wyden said, should now move aggressively to lower drug prices after years of delays.

“If Mitch McConnell and pharma — two very powerful forces — had been willing to go to the Senate floor, we would have been able to get an enormous vote,” Wyden said. “My bottom line is issues like prescription drugs have been kicked down the road again and again and again.”

He didn’t rule out using a budget reconciliation measure — which requires just 50 votes — to pass a more aggressive drug pricing bill than Republicans are willing to support. In the normal legislative process, Democrats will have to get at least 10 Republicans on board with legislation because it takes 60 votes to avoid a filibuster.

A starting place could be H.R. 3 — the bill the Democratic-led House approved at the end of 2019 allowing the health secretary to directly negotiate with drug companies for lower prices. That provision would lower federal spending by about $456 billion over a decade, but it could also result in 40 fewer new drugs being developed over the next two decades, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Yet Wyden acknowledged difficulties in pursuing this course of action. For example, there are strict rules around what can go into a budget reconciliation bill. Democrats will be limited to just two such bills — one for this year and one for next. Plus, they have many competing policy priorities.

This effect is one reason the pharmaceutical industry — and thus many Republicans and some Democrats — hate the idea so much. Because of its vast market power, the government can secure far lower prices when it negotiates for drugs directly (the GOP also argues that direct negotiations would dampen new drug development).

A new report by the Government Accountability Office, provided first to The Health 202, found that Veterans Affairs pays 54 percent less for a unit of drugs than Medicare’s prescription drug program. The report, requested by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), compared how much the government pays for drugs provided through the two programs.

The price differences partly stem from how the two programs are structured.

VA can save so much money partly because it directly purchases drugs from manufacturers on behalf of all of its nine million enrollees.

But Medicare Part D has less leverage with drugmakers. Private insurance plans contract with the government to provide pharmacy benefits. Then each plan, on its own, negotiates prices with manufacturers. So while the program covers 42.5 million people — far more than the VA — its negotiating power is dispersed among many different plans.

In its report, the GAO compared the 2017 prices of 399 top drugs in each program. It also found:

There are statutory discounts available to VA, which also lower its costs for drugs. VA also has more direct control over the medications it will cover, allowing it to steer patients toward certain lower-priced drug options.

All of this bolsters arguments for allowing direct negotiations in Medicare, Sanders argues.

“There is absolutely no reason, other than greed, for Medicare to pay twice as much for the same exact prescription drugs as the VA,” he said, in a statement provided to The Health 202. “If the VA can negotiate with the pharmaceutical companies to substantially reduce the price of prescription drugs, we must empower Medicare to do so as well.”