https://www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/healthpolicy/69102?pop=0&ba=1&xid=fb-md-pcp

The market economy fails when applied to healthcare.

That healthcare expenditures in the US are high and rising rapidly is nothing new, but this study appearing in the Journal of the American Medical Association identifies the exact components of healthcare that are driving those soaring costs. As F. Perry Wilson, MD points out in this 150 Second Analysis, the data suggest traditional economic forces break down in the US healthcare market.

Transcript:

It’s no secret that healthcare costs in the United States are exceedingly high, and rising.

The US spends the most of any country in the world on healthcare in terms of percent of GDP, sitting around 18% as of the most recent data.

But to address the issue, we need to understand what is driving this increase, and a new study appearing in the Journal of the American Medical Association does the best job yet in decomposing the factors behind the rising costs.

The researchers used data from the US Disease Expenditure Project, which utilizes 183 data sources and 2.9 billion patient records to quantify where each healthcare dollar is being spent in this country.

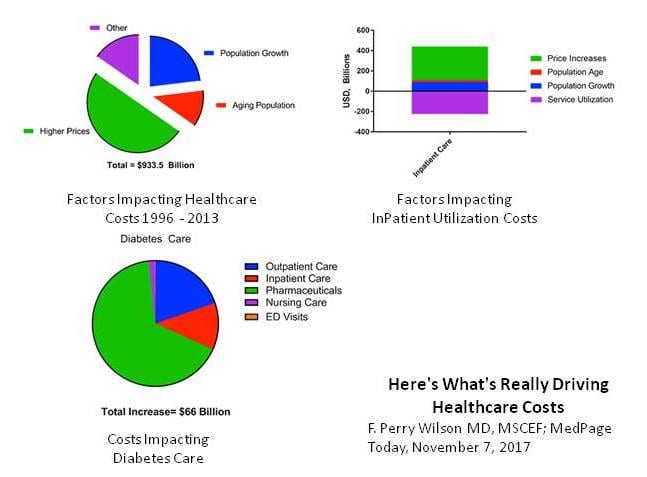

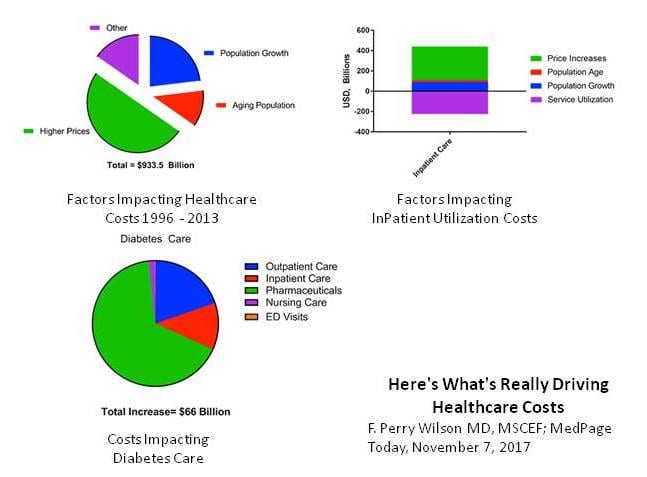

Here’s the top level overview. After accounting for inflation, healthcare expenditures increased by $933.5 billion between 1996 and 2013. To put that into perspective, that’s enough money to create 9 additional interstate highway systems. We could fully fund 3 NASAs every year.

Or we could provide 400 malaria nets to every man, woman, and child in Africa. We could even do something crazy like pay down the debt.

But to save money in the future, we have to know why we keep spending more. Here’s the breakdown.

Some of the increase in spending comes from the aging of the US population and population growth. Not much we can do about that. But 50% of the increase was simply due to higher prices.

This is distinct from healthcare utilization. In fact, healthcare utilization was decreased a bit over this time period. This is shown most dramatically in the data for inpatient care. Take a look at this bar chart.

Use of inpatient care (that’s service utilization – in purple) went down substantially from 1996 – 2013 as we moved to more outpatient treatment. But this may have been a Faustian bargain. The price of the inpatient care that remained went up much more – increasing overall inpatient spending by around 250 billion dollars.

Let’s take a moment to realize how weird this is, economically. Demand for healthcare decreased over time. Prices increased. That is not an efficient market.

Different chronic diseases had different patterns of price increases. The biggest increase was seen in diabetes care, as you can see here, driven largely by rising costs of pharmaceuticals.

Regardless of the disease, though, it is clear that it is the price of what we’re buying – whether a drug, an ED visit, or a hospital stay – not the amount of what we’re buying that is the major driver of cost increases. Efforts to reduce the consumption of healthcare, therefore, may not bend the cost curve as much as efforts to reduce its price. That’s just my 2 cents.