This segment reviews the “Perfect Storm” of reasons for unrestrained increase of healthcare spending in the U.S.

In Episode 4, we zeroed in on what I call the Real Problem with healthcare — relentlessly rising costs.

In this Episode, we will look at why the US spends so much on healthcare. As you can imagine, there are many reasons, not just one. In fact, it’s a perfect storm of bad reasons. We will also look whether we are getting our money’s worth.

Here’s the list. Part 1 & Part 2.

We will go through each one.

Natural Spending Drivers

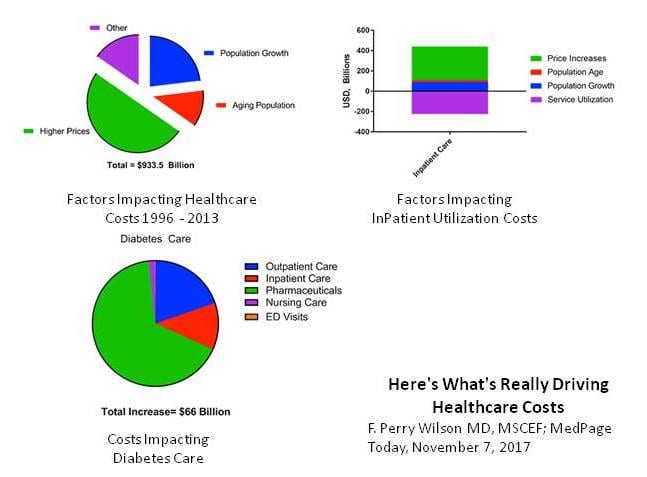

Let’s start with some natural drivers of health spending, which are understandable and expected. First, as the population grows, so will health spending. Likewise, as the proportion of older people increases, so will spending. We also expect health spending to increase slowly with inflation. New technologies and medicines increase cost, but we hope will give dramatic benefits. For example, during my 40-year practice lifetime I have seen the introduction of new drugs for diabetes, blood pressure, and virus infections including HIV and flu. I have seen new ultrasound, CT and MRI diagnostics. I have seen cardiac caths, by-passes and joint replacements. These new things are expensive but well worth the cost.

But health spending grows from 1-1/2 to 4 times the rate of inflation, much more than would be explained by natural drivers, as we saw previously.

Fee for Service Payments

So, let’s look at the other reasons. First and foremost, to my way of thinking, is fee-for-service. Doctors in the US – unlike other countries where they are salaried – get paid for piecework. If a surgeon doesn’t operate, he doesn’t get paid. If a specialist doesn’t have a patient scheduled, HE doesn’t get paid. Money is a powerful incentive. So we should not be surprised if doctors increase their own volume of services, many times unconsciously.

Health Insurance Hides Cost

The next big reason is our health insurance. Until recently premiums were paid by the employer and out-of-pocket copays were minimal. Healthcare felt free to most of us. Most of us had no idea what our care was costing the system, and cared little. Talk about a perfect storm!

Imperfect Market

Why didn’t market forces keep down costs and spending. Many politicians and reformers think competition as the simple solution to the healthcare cost problem. But economists will tell you that healthcare is not a pure market; they refer to it as “imperfect.” The reasons are first that no one knows the true price of anything. Have you ever tried to sort out a hospital bill? Ridiculous!

Second, markets rely on buyer and seller having equal footing to negotiate, but most patients dare not quibble with their doctor. Doctors get their feathers ruffled when patients challenge their advice. Third, to make matters worse, patients are a “captive market” – they are often suffering, frightened for their life, and desperate for immediate relief, not exactly a strong bargaining position. Fourth, doctors can control demand. There’s an old joke about the level of eyesight loss that needs a cataract operation – if there’s one doctor in town it’s 20/100, if two doctors it’s 20/80 and if three doctors in town it’s only 20/60.

Administrative Costs

Next is administrative costs. Some economists estimate that up to ¼ of all health spending is for administration, not actual care. This is not surprising knowing how complicated we make our delivery system and financing system. Other countries have one delivery system and one payment system. US has 600,000 separate doctors, 5,500 separate hospitals, and 35 different insurance companies, not counting Medicare and Medicaid. Doctors used to drown in papers; now we spend up to 2 hours doing computer work for every hour of patient care. Don’t you love it?

For comparison, Medicare reports only 2% administrative costs (but some other costs are hidden elsewhere in government).

Inefficiency & Waste

Some other spending drivers include inefficiency. I include in this category unnecessary tests and treatments, as well as wasted effort due to incompatible computerized record systems – there are 632 separate electronics vendors in the US. If airports ran this way, each airline at each airport would have its own unique air traffic control computer that did not connect with each other. All in the name of free market.

Regards unnecessary treatments and procedures, a doctor at Dartmouth named John Wennberg pioneered using Big Data in the 1980s to look at numbers of prostate operations in each individual ZIP code, and found that surgeons in some regions were operating 13 times for often in highest areas than the lowest. Since prostate disease is relatively constant everywhere, this can only mean that doctors practice varies widely – the highest utilizers are doing too many operations.

Monopolies

Next is monopolies. Many small- and medium-sized towns and rural areas can only support one hospital. This creates monopolies with no market forces whatsoever to hold down charges.

Cost Shifting

Cost-shifting means that uninsured patients come to the ER for care. Since the ER doesn’t get paid, the ER shifts the Uninsured cost into the bill for INSURED and Medicare patients. The cost-shifting itself doesn’t increase the costs, but getting care in an ER instead of doctor’s office is the most expensive possible place for care.

New-Technology Policy

The FDA new-technology policy means that FDA rules say that it will approve any new drug or treatment if it shows even the slightest statistical benefit, no matter how small. Some cancer drugs are approved that extend life by only a few weeks. Some medicines are approved, even if the number needed to treat is 100. For example, for some new cholesterol medications, 100 patients need to be treated for 5 years before we see even 1 heart attack prevented. That’s a lot of patients, and a lot of doses, and a lot of dollars. By comparison, since half of appendicitis patients die without treatment, and almost all with appendectomy surgery survive and live happily ever after, the calculated number-needed-to-treat is only 2. So appendectomies are a good valued, but cholesterol medication (for otherwise healthy people) is questionable value.

Non-Costworthy Marginal Benefit

Here is another way of looking at value. As we go from left to right in this graph, we are spending more and more on health care. The more we spend, the higher the cumulative health benefit, at least to start. The first section (Roman number I) are very high value interventions like public health, sanitation, immunizations. The next section (Roman number II) are good value routine health treatments, including kidney dialysis and first-line chemotherapy for treatable cancers. But when we reach the third section (Roman number III), the benefits level off. Bypass surgery is less effective for older patients (and more risky); dying patients don’t survive in intensive care units and are miserable with tubes and futile breathing machines. If we spend even more we reach section Roman numeral IV in which no additional benefit is gained, just a lot of extra testing, treatments or drugs – these are wasted dollars. And if we keep spending more yet, we actually do more harm than good, and can even have deaths on the operating table or reactions to too many drugs. The US is well into section IV and in some cases section V. A lot of other richer countries think that they have already reached the point where spending more will give no benefit or possibly do more harm than good, even though they spend less than the US.

In the next episode we will look at the ramifications of so much health spending on the US economy, politics and society. We will look at some potential threats if we do not start to control costs better.

I’ll see your then.