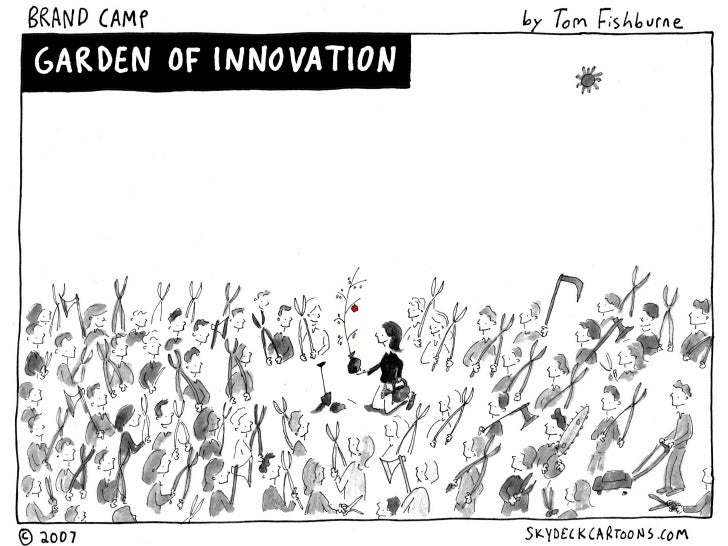

COURAGE IS THE FIRST VIRTUE of organizational performance. Consider, for example, all the other concepts that courage connects to in workplace settings. Leadership takes courage because it requires making bold decisions that some people won’t agree with or support. Innovation takes courage because it requires creating ideas that are ground-breaking and tradition-defying; great ideas always start out as blasphemy! And sales always take courage because it requires knocking on the doors of prospects over and over in the face of rejection. These aspects of work simply can’t exist in the absence of courage.

That’s why it’s crucial to instill courage in those you lead, both in their development and training programs, but also by leading by example. There’s a lot you can do as a leader toward this end: rewarding jumping first, creating safety nets to make trying and failing a palatable option, teaching to harness fear, and modulating comfort levels are all management tools for setting a foundation that supports and encourages courageous behavior. But while courage in the abstract is an easy thing to get behind, in practice it’s more useful to break it down into different types of courage. Having a way of categorizing courageous behavior allows you to pinpoint the exact type of courage that each individual worker may be most in need of building.

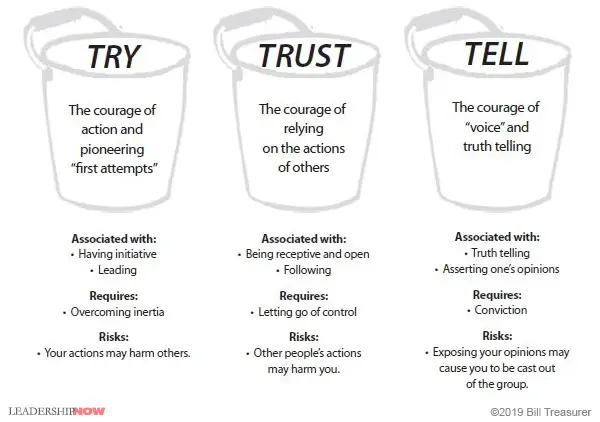

I think of courage as falling into three distinct buckets: TRY, TRUST, and TELL Courage. Let’s talk about each.

TRY Courage

The first bucket of courage is TRY Courage. TRY Courage is the courage of action. It is the courage of initiative. TRY Courage requires you to exert energy in order to overcome inertia. Certainly, it is easier not to do something than to do it, which is one reason why many people prefer to stay in their “comfort zones.” It takes courage to TRY something, particularly when you’ve not done it before. This is the kind of courage that’s demonstrated when someone “steps up to the plate,” for example, taking on a project on which others have failed. You experience your TRY Courage whenever you must attempt something for the very first time, as when you cross over a threshold that other people may have already crossed over.

The courage of try is associated with:

- “Stepping up to the plate,” such as volunteering for a leadership role.

- First attempts; for example, the first time you lead an important strategic initiative for the company.

- Pioneering efforts, such as leading an initiative that your organization has never done before.

- Taking action.

All courage buckets come with a risk, and the risk is what causes people to avoid behaving with courage. The risk associated with TRY Courage is that your courageous actions may harm you, and, perhaps more importantly, other people. If you act on the risk and wipe out, not only are you likely to be hurt, but you could also potentially harm those around you. It is the risk of harming yourself or others that most commonly causes people to avoid exercising their TRY Courage.

TRUST Courage

TRUST Courage involves resisting the temptation to control other people. Unlike TRY Courage, TRUST Courage is not about action. Instead it often involves inaction, or “letting go” of the need to control. With TRUST Courage, you step back and follow the lead of others. A common example of TRUST Courage is delegation. TRUST Courage is very hard for people who tend to be controlling and those who have been burned by trusting people in the past. TRUST Courage, though, is a crucial element in building strong bonds between people.

The courage of trust is associated with:

- Releasing control, such as delegating a task without hovering over the person to whom you’ve delegated.

- Following the lead of others, such as letting a direct report facilitate your meeting.

- Presuming positive intentions and giving team members the benefit of the doubt.

TRUST Courage, of course, comes with a risk. The risk associated with TRUST Courage isn’t that you will harm other people, but that by trusting them, they might harm you. By trusting others, you open yourself up to the possibility of your trust being misused. Thus, many people, especially those who have been betrayed in the past, find offering people trust very difficult. For them, entrusting others is an act of courage.

TELL Courage

The third bucket of courage is TELL Courage, which is the courage of voice. TELL Courage is what is needed to tell the truth, regardless of how difficult that truth may be for others to hear. It is the courage to not bite your tongue when you feel strongly about something. Brown-nosing and people pleasing are symptoms of low TELL Courage. TELL Courage requires independence of thought. We also use our TELL Courage when we take responsibility for a mistake or offer an apology. Whenever we speak up and say what’s hard to say, whether it be speaking truth to power, admitting a mistake, or saying “I’m sorry,” we are using TELL Courage.

The courage of TELL is associated with:

- Speaking up and asserting yourself when you feel strongly about an issue.

- Telling the truth, regardless of where the person to whom you are telling the truth resides in the organizational hierarchy, such as presenting an idea to your boss’s boss.

- Using constructive confrontation, such as providing difficult feedback to a peer, direct report, or boss.

- Admitting mistakes and saying, “I am sorry.”

TELL Courage can be scary and comes with risks too. We avoid using TELL Courage because we don’t want to offend others and fear being cast out of the group. The need for affiliation with those we work with is very strong, and the risk of TELL Courage is that, by speaking up and asserting ourselves, we will be cast out of the group and won’t “belong” anymore.

Courage is Contagious

Understanding (and influencing) courageous behavior requires that you be well versed in the different ways that people behave when their courage is activated. By acting in a way that demonstrates these different types of courage, and by fostering an environment that encourages them, you can make your company culture a courageous one where employees innovate and grow both personally and professionally. Here’s a handy diagram to remind you of these types of courage and what they require: