Tag Archives: Strategy

The false promise of “no regrets” investments

At the end of my meeting last week with a health system executive team, the system’s COO asked me a question: “Your concept of Member Health describes exactly how we want to relate to our patients, but we’re not sure about the timing. Could you give us a list of the ‘no regrets’ investments you’d recommend for health systems looking to do this?”

We frequently get asked about “no regrets” strategies: decisions or investments that will be accretive in both the current fee-for-service system as well as a future payment and operational model oriented around consumer value. The idea is understandably appealing for systems concerned about changing their delivery model too quickly in advance of payment change. And there is a long list of strategies that would make a system stronger in both fee-for-service and value: cost reduction, value-driven referral management, and online scheduling, just to name a few.

But as I pointed out, the decision to pursue only the no-regrets moves is a clear signal that the organization’s strategy is still tied to the current payment model. If the system is really ready to change, strategy development should start with identifying the most important investments for delivering consumer value.

It’s fine to acknowledge that a health system is not yet ready, but I cautioned the team that they should not rely on the external market to provide signals for when they should make real change. External signals—from payers, competitors, or disruptors—will come too slow, or perhaps never.

At some point, the health system should be prepared to lead innovation, introduce a new model of value to the market and define and promote the incentives to support it. Real change will require disruption of parts of the current business and cannot be accomplished with “no-regrets investments” alone.

Getting Distracted by the Politics of Healthcare

A number of interactions over the past two weeks have convinced me that the political debate over M4A in Congress, amplified by Presidential candidates jockeying for favor with primary voters, is beginning to seriously spook executives across healthcare.

At a health system board meeting in the Southwest last week, a number of physician leaders and board members had questions about the possible timing and dimensions of a shift to “single payer”, clearly convinced that M4A is an inevitability if Democrats take over in 2020. And two separate inbound calls this week, one from the CEO of a regional health system, and the other from a health plan executive, were both sparked by the hearings on M4A in Congress.

Again, the implicit assumption in their questions about timing and impact was the same: M4A, or something like it, is sure to happen if the 2020 elections favors Democrats. My response to all of them: keep an eye on the politics, but don’t get overly distracted. There’s little chance that “single payer” healthcare will come to the US—industry lobbies are simply too powerful to let that happen.

Even if Democrats do win the Senate and the White House in 2020, they’ll have to “govern to the center” to hold onto their majorities, and any major policy shifts will have to be negotiated across the various interests involved. Most likely: measures to strengthen provisions of the ACA, and perhaps a “public option” in the ACA exchanges.

As to Medicare expansion, I believe the most we’d see in a Democratic administration would be a compromise allowing 55- to 65-year-olds to buy into Medicare Advantage plans.

But for now, M4A’s biggest risk to hospitals and doctors is that it becomes a paralyzing distraction, keeping provider organizations from making the strategic and operational changes needed to re-orient care delivery around value.

Regardless of the politics, a focus on delivering value to the consumers of care will prove to be a no-regrets position for providers.

Megamergers Take Center Stage in M&A Activity

https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/strategy/megamergers-take-center-stage-ma-activity

Despite continued and sometimes unsettling M&A activity in the industry, the fundamental mission of healthcare has not changed.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

73% of healthcare executive respondents will be exploring potential M&A deals during the next 12–18 months, according to a new HealthLeaders survey.

The recent M&A movement toward vertical integration involving nontraditional partners suggests that the healthcare industry is undergoing a major transformation.

Merger, acquisition, and partnership (M&A) activity within the healthcare industry shows no sign of diminishing, with nearly all indicators pointing to continued consolidation, according to a 2019 HealthLeaders Mergers, Acquisitions, and Partnerships Survey. The fundamental need for greater scale, geographic coverage, and increased integration remains unchanged for providers, and this will sustain M&A activity for years to come.

Evidence of the M&A trend’s resiliency is found throughout the HealthLeaders survey. For example, 91% of respondents expect their organizations’ M&A activity to increase (68%) or remain the same (23%) within the next three years, an indication of the trend’s depth. Note that only 1% of respondents expect this activity to decrease.

Likewise, 38% of respondents say that their organization’s M&A plans for the next 12–18 months consist of exploring potential deals, up six percentage points over last year’s survey, and another 35% say that their M&A plans consist of both exploring potential deals and completing deals underway. This means that nearly three-quarters (73%) of respondents will be exploring potential deals during this period.

Megamergers and industry impact

While steady healthcare industry M&A activity has been with us for some time, a series of new and rumored megamergers and partnerships is capturing the headlines these days. This recent M&A movement toward vertical integration involving nontraditional partners suggests that the healthcare industry is undergoing a major transformation, one that will likely alter the landscape in unanticipated ways.

The majority of respondents in our survey say that they expect significant industry impact from these megamergers, led by CVS Health’s merger with Aetna (68%), Walmart’s potential deal with Humana (57%), and Amazon’s partnership with JPMorgan Chase and Berkshire Hathaway (49%). While information regarding the latter two developments is still in short supply, respondents see the potential for large-scale impact.

Faced with such far-reaching and transformative new relationships, what are healthcare providers to do? As things currently stand, even the largest health systems lack the scale to negotiate on equal footing with most insurers, and these new hybrid organizations combine scale, technology, and innovative structures.

However, there is no need for providers to panic—these megamergers are still in the early stages of implementation, and the fundamental mission of healthcare has not changed.

“I don’t think people fully understand the real business purpose of this type of activity yet, or what these organizations are trying to get out of their connections,” says Kevin Brown, president and CEO of Piedmont Healthcare, a Georgia-based nonprofit health system with 11 hospitals and nearly 600 locations. “Time will tell regarding the impact they will have on the industry landscape and its different segments.”

“I haven’t spent a lot of time thinking or worrying about these new developments. Generally, I spend my time thinking about what we are doing on a day-to-day basis as an organization to fulfill our mission and take care of the communities we serve. I’m certainly aware of these developments, but it’s important not to get distracted from our core purpose,” Brown says.

Hospitals look to venture capital as R&D extension

https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/hospitals-look-to-venture-capital-as-rd-extension/549854/

Academic and nonprofit hospitals are increasingly embracing venture capital as a way to test new technologies, a shift away from the traditional reliance on developing in-house intellectual property.

Since their founding days, providers like Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic have leaned heavily on investing in IP to test new products and services. More recently, players like Tenet, Trinity and Community Health Systems have become comfortable investing in externally-run funds. Now, hospitals of all sizes, types and tax status are giving corporate venture capital funds, where they invest directly in companies, a go.

Hospital fund managers perceive the financial risk in the same light they see other investments, except venture capital can offer hospitals more flexibility. It’s how health systems like Intermountain think of R&D.

Mike Phillips, managing director of Intermountain Ventures, told Healthcare Dive venture funds offer hospitals a chance to “double dip.” If an investment is successful, the outcomes are positive both clinically and financially.

Most don’t take the lead on investments, preferring to take a minority stake. Hospitals see venture as a way to bring in and test out new technologies.

“If they (the startup) can get a champion in the organization that really helps refine it, improve it, augment it, that is much more valuable than the money,” Mary Jo Potter, an investor and consultant in the field, told Healthcare Dive.

Potter cautioned against expecting too much too soon. It typically takes take 10 years to get an exit and even then, returns are most likely to be in the range of twice or triple the investment. Well over half of the health system-linked venture funds are less the five years old, Potter said.

UPMC Enterprises, the venture capital arm of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, made $243 million when its population health management spinout Evolent Health went public in 2015, according to UPMC Treasurer Tal Heppenstall, and the nonprofit still retains stock.

Heppenstall, who also leads UPMC Enterprises as president, told Healthcare Dive the health system plans on spinning out two companies by the middle of this year. That would bring its count to five as part of its “renewed focus on the translational science space” — finding business applications for medical research.

In February, the fund participated in a $15 million investment in data analytics company Health Catalyst. UPMC will pilot Health Catalyst’s products in-house.

Early entrants

Ascension seeded its first venture fund with $125 million in 1999, making its first investment ($8.4 million in radiation system TomoTherapy) two years later. Eventually, Ascension decided to bring in limited partners to help close the fund.

Ascension Ventures now currently manages $805 million across four funds.

Kaiser Permanente Ventures is an active investor in its own right. The venture arm of the hospital system manages $400 million in assets over four funds, with 28 exits, according to CB Insights.

Early adoption of CVC by health systems like Ascension and Kaiser paved the way for health systems that want to give venture a try, but want to start slow as limited partners. In recent years, deal flow is ramping up at a healthy clip.

Deals involving at least one provider-backed venture fund totaled nearly $1.3 billion in 2018, according to PitchBook, an all-time high — and on track with overall corporate venture capital participation in the healthcare sector, which CB Insights reports having jumped 51% to $10.9 billion last year.

Newly-seeded funds are springing up in health systems across the country. Providence St. Joseph Health, one of the largest health systems in the country and most active in the venture space, announced its second $150 million healthcare venture capital fund in January, managed by its venture arm Providence Ventures. Providence Ventures’ first fund was launched in 2014.

Starting small

Like many smaller health systems establishing themselves as new players in venture capital, Intermountain made its foray into the space as a limited partner in larger funds managed by Heritage Group and Ascension.

Large firms “have a lot of understanding in how to help manage young companies and get them through the business end of growing their company. We can help on the clinical end,” Phillips said. “We definitely rely on the other folks investing … to both learn from and be a good partner to the companies we invest in.”

Intermountain formally launched its first $80 million venture fund this year.

While the health system recognizes the risk, Phillips argued many hospitals have institutional knowledge most investors don’t. That, in theory, allows them to mitigate some of that risk.

Intermountain’s portfolio is comprised partially of the companies the hospital system spun out of R&D. That’s not uncommon for nonprofit and academic health systems that have traditionally focused on developing IP in-house. As of 2017, 90% of Cleveland Clinic Ventures’ portfolio was invested in IP owned by the health system.

IP is the bread and butter investment for most academic and nonprofit health systems, helping to bring in some return while allowing physicians, who often develop those patents themselves, to retain some benefit.

Mayo Clinic, for example, says it has generated $600 million in revenue from licensing its IP since 1986. The health system has recently rolled its venture activity into its R&D arm under the name Mayo Clinic Ventures. Nevro, a device company the system spun out in 2014, has a current market cap of $1.32 billion.

Hospital executives like to say CVC is a complementary tool to R&D, that it’s another way to tinker — that the money doesn’t matter as much as the ability to improve quality and decrease cost does. That may be true, but at the end of the day it’s an investment, and hospitals have to hope it yields a positive return.

If there’s a chance an investment can lower the cost of care, increase quality and improve clinical care, Phillips said, the bigger risk is not giving it a shot.

Scale: blessing or burden for statewide ACOs?

https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/scale-blessing-or-burden-for-statewide-acos/551206/

Scale can smooth out quality variation and assuage providers’ fears of taking on risk. But it’s not a catch-all solution.

A handful of accountable care organizations are moving to cover an entire state, but not everyone thinks bigger is better when it comes to population health management.

Caravan Health, a company that works with ACOs, last week announced the launch of its second statewide program, this time in Florida. In the model, any of the 200-some Florida Hospital Association facilities that want to participate can join together to provide coordinated care.

The bid is meant to bolster care quality for Medicare beneficiaries while lowering costs and risk for participating facilities. But some experts say the larger scale, like rampant consolidation, could be more like an anchor weighing down an ACO instead of a beam propping it up.

“At the end of the day, success or failure is based on success in managing the quality of care,” Michael Abrams, partner at Numerof & Associates told Healthcare Dive. “While there may be some bigger numbers involved, I think the safety angle that they’re selling may not be all it’s cracked up to be.”

Caravan has no plans to back down on the model, however, and plans to roll out two more statewide ACOs in the next couple of weeks.

ACOs existed before the Affordable Care Act, but in 2011 HHS released new rules under the landmark law aimed at helping providers coordinate care through the population health management programs. Since then, the number of ACOs have grown dramatically, from an estimated 32 to more than 1,000 in 2018, according to Leavitt Partners.

A statewide all-payer ACO in Vermont has seen some success, but Caravan’s model and its efforts are some of the first to leverage the programs over a much larger population.

The business model

The Florida ACO, created in partnership with the FHA, is the second from Kansas City-based Caravan. The first, in Mississippi, was launched in January. Under the program, hospitals have access to Caravan’s population health management model to build primary care capacity and monitor quality results.

Mississippi currently has 29 providers participating in the program, managing care for roughly 130,000 Medicare patients in 22 locations. Its operations include hiring and training population health nurses throughout the state, annual wellness visits, chronic care management and more.

It’s potentially a good business playbook for both parties. The hospital association captures a revenue stream that’s not dependent on their membership — increasingly important in these days of sharp provider headwinds — and Caravan is granted access to the Medicare lives of a couple hundred hospitals in the state.

The need for population health management is especially acute in Mississippi, which ranks last or close to last in every leading health outcome, according to the state Department of Health. Florida and Mississippi couldn’t be farther apart when it comes to their primary care infrastructure, a factor linked to ACO success. According to the NCQA database, Florida has 894 patient-centered medical homes. Mississippi has 74.

“With population health, we improve the health of our state so it’s a win-win all the way around,” Paul Gardner, the director of rural health at the Mississippi Hospital Association told Healthcare Dive.

And Caravan, which currently works with more than 225 health systems and 14,000 providers, touts its track record with its programs. In 2017, its ACOs beat nationwide ACO performance with savings of $54 million and quality scores of 94%, a spokesperson said.

By comparison, studies have yielded mixed results when it comes to ACO success elsewhere.

An April report from Avalere found the Medicare Shared Savings Program, a CMS model to foster ACOs in Medicare, missed federal cost-savings projections from 2010 by a wide margin and raised federal spend by $384 million.

But a National Association of ACOs analysis retorted that MSSP ACOs saved $849 million in 2016 alone, and a whopping $2.66 billion since 2013 (higher than CMS’ $1.6 billion estimate). And an early 2017 JAMA Internal Medicine analysis found ACO savings only increase with time.

Scale: protection or illusion?

The threat of financial loss is a leading obstacle to participation in ACOs. Smaller ACOs are more likely to experience widely variable savings and losses simply due to change, Caravan representatives say, while larger ACOs deliver more predictable and sustainable results.

“The only way we can create certainty around our income is to have processes and accountability and the infrastructure, but you’ve also got to have to scale,” Caravan CEO Lynn Barr told Healthcare Dive. Barr said that since Caravan’s 2014 inception, the company has found having 100,000 Medicare lives or more in an ACO yields larger savings than the roughly 80-85% of ACOs with only 20,000 lives or fewer.

As the owner of the ACOs, Caravan assumes 75% of the financial risk for providers. Barr said that evens out to a maximum risk of $100 per patient.

By comparison, in the basic track of the Medicare Shared Savings Program, the maximum risk for providers is $400 per patient. In the enhanced model it’s $1,500. “With our model, if people follow it and have 100,000 lives, there’s no reason they would ever write a check,” Barr said.

That is one of the selling features of the statewide ACO: It can be a mitigating factor for hospitals that might feel too exposed on their own, Abrams said.

But the threat of risk could still prove too much. CMS finalized new rules for shared savings ACOs in December, shaving down the amount of time they had before they were forced to assume downside risk from six year to two years for new ACO participants or three years for new, low-revenue ACOs.

And some critics say it’s a safe bet that the losses incurred by any one organization are not going to be spread across the other parties in the ACO, especially given the shortened timeline. As the deadline for assuming more risk approaches, Caravan could see attrition among providers who don’t feel ready.

“I think this is very, very, very challenging,” nonprofit primary care advocacy Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative Director Ann Greiner told Healthcare Dive. “Most of the hospital leadership has not been working under these kinds of conditions.”

And ACOs are all about a connection to the community, which might prove difficult to foster across an entire state.

“You’ve got to leverage people at the community level and have those relationships with the patient and, in the ideal world, know where to refer,” Greiner said. “At the state level, that’s pretty far removed.”

Unified governance, heterogeneity pose problems

The scale of large ACOs makes them much more difficult to manage, experts say. ACOs have a single set of policies that, in an organization involving more parties, needs to be adopted in one form or another that’s acceptable to all participating providers.

That’s done by majority, Barr said. Each participating provider has a single vote and the overall vote binds the ACO board’s decision on waiver approval, discharge standards, shared savings distribution plans and more.

But in an ACO with a lot of differently cultured and structured providers — academic hospitals, teaching hospitals, acute care, research, small, medium, large etc. — it can get a lot more complicated, Abrams said. For example, if 100 FHA hospitals opt into the new Caravan Health model, that’s 100 variations in acute care policy, physician compensation and all else involved in managing cost and quality operations, and 100 different voices strongly advocating to keep doing things the way they’ve always done them.

“Some issues are just working through the details,” Gardner from the Mississippi Hospital Association said. “In some of your larger systems, that’s getting the medical staff all pulled together and singing off the same sheet of music.”

The more homogeneous the ACO organizations are, the easier it will be to get them to buy in to the various policies and procedures that need to be put in place for operations to flow smoothly. “You can’t outsource that,” Abrams said. “The most you can do is get guidance from someone who’s perhaps been around this block about how to handle it.”

Barr maintains Caravan standardizes the most important factors.

“Nurses are critical to this model,” Barr said. “That’s what everyone’s doing the same.” Caravan has found that after nurses are trained in population health management over three to six months, each dollar the company spends on that provider produces two dollars in savings.

And, after Caravan puts the population health management infrastructure in place, the providers themselves helm the ship with a steering committee, leveraging data to see what differentiates them from the next community and making slight adjustments to course-correct.

Challenges for hospitals

Hospitals will face two challenges: taking in the coordinated framework given to them by Caravan and translating it into behavioral change, Abrams said. The success of the overall ACO will depend on the latter as “those who can’t do that successfully will probably self-select out when it comes time to take on risk.”

The question is whether Caravan can really deliver on some of the promises it’s explicitly making.

“The truth is that hospitals who haven’t had the infrastructure to manage their cost and quality are not better off in terms of consolidation and a position in a larger ACO,” Abrams said. “So an ACO comprised of multiple small hospitals and independent hospitals can’t expect savings proportionate to their aggregate size.”

With more statewide ACOs on the way, it’s important Caravan (and partnering providers) work out any kinks in the model sooner rather than later.

“This is not like bringing in a plumber to fix your faucet,” Abrams said. “At the end of the day, an organization stands on its own.”

Consolidating Retail Medicine: Positioning Single Specialty Practices for Acquisition

Click to access CBC_59_032719.pdf

Funded by Private Equity, the ongoing consolidation of solo and small-group physician practices into Physician Practice Management organizations reflects a maturing healthcare marketplace that is repositioning to deliver single specialty care services in retail settings.

Time is running out for solo and small group practices. To position themselves for successful consolidation transactions now and in the future, operators and buyers need to understand the fundamental market dynamics shaping valuations.

Narrowing choice to curb rising employer spend

https://gisthealthcare.com/weekly-gist/

When Presbyterian Health System struck a deal with Intel to manage care for the firm’s Albuquerque employees, followed by Providence Health & Service’s ACO-like contract to provide care to Boeing employees in Seattle, we became optimistic about the potential of direct contracting between health systems and large employers.

But five years after those landmark deals, we were still just talking about Boeing and Intel. Few other employers followed suit, instead preferring to control spend by shifting more of the cost of coverage onto their employees in the form of higher deductibles, larger co-pays, and greater co-insurance.

In 2018 the average family deductible in employer-sponsored insurance hit $3,000, and in most markets deductibles of $5,000 or higher are not uncommon. Our recent conversations with employers suggest that they are now questioning the utility of shifting more costs onto employees. As deductibles rise, employers see diminishing returns. In contrast to instituting the first $1,000 deductible, moving an already high deductible from $3,000 to $4,000 does little to change employee behavior. And employers are genuinely worried about the impact of rising cost sharing on their employee’s financial and physical health.

Given the historically strong labor market, employers have been reticent to change benefit design in any way that could be perceived as narrowing choice. But the reluctance to push cost sharing further creates an opening for providers and innovators that offer alternative solutions to encourage employees to choose a “high-performance network”—the new term of art for a narrow network.

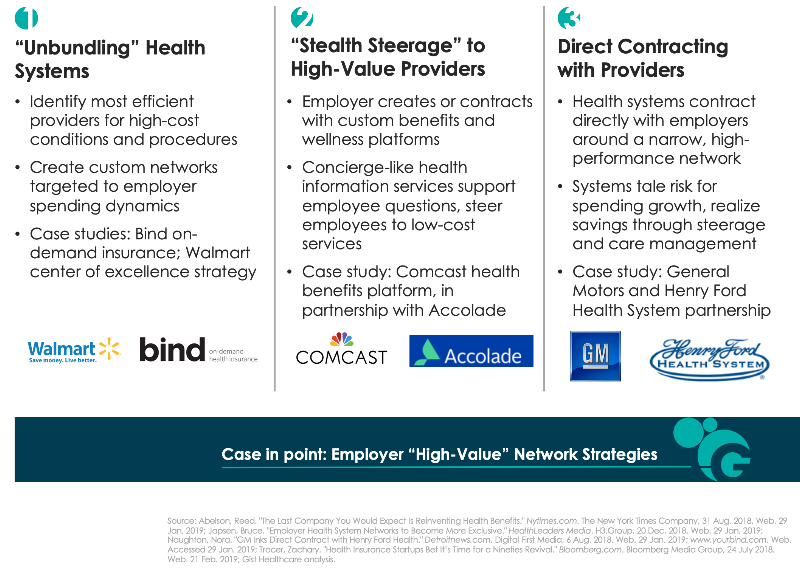

Across the past year we’ve seen a range of strategies to create high-performance networks, described in the graphic below. The pace of direct contracting between health systems and employers has quickened. But other solutions challenge the premise that a single health system provides the best solution for every high-cost condition or procedure. Start-up insurer Bind aims to create bespoke networks for high-cost procedures by identifying the best doctors and hospitals regardless of affiliation, essentially “unbundling” the health system. Others, like health benefits solution provider Accolade, create a concierge-like service to support employee decision-making—while preferentially steering them to lower-cost providers.

It remains to be seen which of these solutions will produce the greatest returns, and whether the gains can be sustained over time. However, we wonder whether companies will really have the fortitude to engage employees in conversations about narrower networks. Many will likely prefer to shift the task of narrowing networks onto employees themselves; we still believe that defined contribution health benefits will be the ultimate solution for employers to manage spend. It’s likely employers will require the cover of a recession to make this dramatic switch in benefit design. In the interim, there seems to be a window of opportunity for high-performance network assemblers to demonstrate that they can be an attractive and effective solution to rising costs.

Moving beyond the “best practice” mindset

https://gisthealthcare.com/weekly-gist/

Here’s a question we get all the time, and one that I heard again this week from one of our partner health systems: “We’re working on [initiative X]. What have other health systems like us done about that?” We hear it in any number of situations, from hospitals developing clinical protocols to strategic planners putting together business plans for service line growth. Sometimes the question comes in different forms: “Do you have a white paper on [topic X]?”; or “What research do you have on [issue X]?”; or our favorite, “What’s the best practice for [activity X]?”

It’s not surprising, given our past history, that we’d frequently be asked to provide research or best practice information. But as we’ve grown our own business at Gist Healthcare and developed our own independent perspective on where our industry needs to go, we’ve become less and less impressed by “best practice” as a concept. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that “best practice” has become at best a crutch, and in many cases a hindrance, to real progress in healthcare. As we sometimes tell our clients now, healthcare has outgrown “best practice”, at least as we used to understand it.

Don’t get me wrong. Medicine should absolutely be evidence-driven, and clinical care should always be firmly grounded in proven practice. If anything, the actual clinical practice of medicine is one area where our industry must become more, not less, best-practice based.

But as to system strategy, payment innovation, service improvement, and a host of other business and operational issues, simply imitating what other “successful” organizations are doing leads inevitably to reversion to the mean, groupthink, and (most troubling) fad-driven “bubbles” of activity. It’s no surprise, given the pervasive culture of “best practice”, when suddenly every health system’s top priority turns to creating a patient portal, or hiring a chief experience officer, or starting a proton beam center, or opening freestanding EDs.

Healthcare delivery is a highly fragmented, insular business, with little visibility across markets and across institutions. That makes it very susceptible to white paper-driven trend chasing, which tends to outsource innovation to the “wisdom of the crowd”.

It’s pretty rare to find mavericks, following their own innovation instincts without getting caught up in trying to mimic what other “leaders” are doing. That’s why when a delivery organization takes a risk on a truly new strategic innovation—Geisinger’s money-back guarantee, Cleveland Clinic’s promise of same-day access, Presbyterian’s direct contract to manage Intel employees’ health—it immediately sends shock waves across the industry.

Those ideas didn’t come from a white paper. We’re often asked whether we’re building a “best-practice research” capability in our new company. While we’re not quite ready to talk about our upcoming service offerings, the answer to that question is a definitive “no”.

The noble aim of being a great subcontractor

https://gisthealthcare.com/weekly-gist/

Earlier this month I was at a health system board meeting in which we were discussing the transition from volume to value, and the shift to a population health model. One board member had the courage to ask a tough question: “What if we never get there?” Covering just a small slice of a large metropolitan area, this system has consistently ranked third in market share behind two larger competitors—and now they feel they are lagging those systems in moving toward risk. The most recent challenge: a large—and until recently, loyal—independent primary care group had just been acquired by one of their competitors. Yet the system prides itself, justifiably, on delivering low-cost hospital care and outstanding quality.

I raised a heretical notion: suppose the system pursued a strategy focused solely on being the highest-performing inpatient and specialty care provider in the market, and abandoned the goal of bearing population risk? Could the system shift their focus to simply being the best “subcontractor” to other risk-bearing networks in the market?

The ensuing conversation was uncomfortable, to say the least. The notion challenged the system’s assumptions of the role they wanted to play in the market, and whether they could be a leader in population health. I encouraged them to think of being a “subcontractor” to other risk-bearing organizations not as a defeat, but as fulfillment of a vital role—healthcare in their community would be better if more hospital care were delivered at their level of cost and quality.

Our view: for many smaller systems who are driven by a desire to remain independent, becoming a high-performing care subcontractor may be the best path forward, and the most realistic. (It will be interesting to watch the successful investor-owned chains on this front—organizations whose strategic advantage lies in running highly-efficient, low-cost hospitals.) It’s not as sexy as “population health”, but as any builder will tell you, there’s no substitute for a great subcontractor.