Why the U.S. Spends So Much More Than Other Nations on Health Care

The United States spends almost twice as much on health care, as a percentage of its economy, as other advanced industrialized countries — totaling $3.3 trillion, or 17.9 percent of gross domestic product in 2016.

But a few decades ago American health care spending was much closer to that of peer nations.

What happened?

A large part of the answer can be found in the title of a 2003 paper in Health Affairs by the Princeton University health economist Uwe Reinhardt: “It’s the prices, stupid.”

The study, also written by Gerard Anderson, Peter Hussey and Varduhi Petrosyan, found that people in the United States typically use about the same amount of health care as people in other wealthy countries do, but pay a lot more for it.

Ashish Jha, a physician with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, studies how health systems from various countries compare in terms of prices and health care use. “What was true in 2003 remains so today,” he said. “The U.S. just isn’t that different from other developed countries in how much health care we use. It is very different in how much we pay for it.”

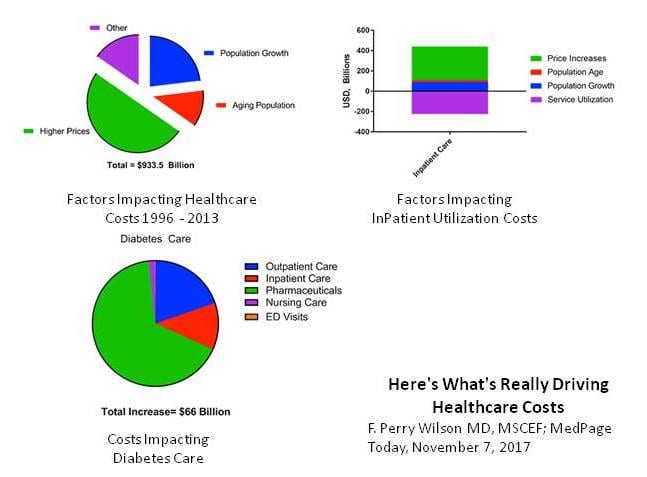

A recent study in JAMA by scholars from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle and the U.C.L.A. David Geffen School of Medicine also points to prices as a likely culprit. Their study spanned 1996 to 2013 and analyzed U.S. personal health spending by the size of the population; its age; and the amount of disease present in it.

They also examined how much health care we use in terms of such things as doctor visits, days in the hospital and prescriptions. They looked at what happens during those visits and hospital stays (called care intensity), combined with the price of that care.

The researchers looked at the breakdown for 155 different health conditions separately. Since their data included only personal health care spending, it did not account for spending in the health sector not directly attributed to care of patients, like hospital construction and administrative costs connected to running Medicaid and Medicaid.

Over all, the researchers found that American personal health spending grew by about $930 billion between 1996 and 2013, from $1.2 trillion to $2.1 trillion (amounts adjusted for inflation). This was a huge increase, far outpacing overall economic growth. The health sector grew at a 4 percent annual rate, while the overall economy grew at a 2.4 percent rate.

You’d expect some growth in health care spending over this span from the increase in population size and the aging of the population. But that explains less than half of the spending growth. After accounting for those kinds of demographic factors, which we can do very little about, health spending still grew by about $574 billion from 1996 to 2013.

Did the increasing sickness in the American population explain much of the rest of the growth in spending? Nope. Measured by how much we spend, we’ve actually gotten a bit healthier. Change in health status was associated with a decrease in health spending — 2.4 percent — not an increase. A great deal of this decrease can be attributed to factors related to cardiovascular diseases, which were associated with about a 20 percent reduction in spending.

This could be a result of greater use of statins for cholesterol or reduced smoking rates, though the study didn’t point to specific causes. On the other hand, increases in diabetes and low back and neck pain were associated with spending growth, but not enough to offset the decrease from cardiovascular and other diseases.

Did we spend more time in the hospital? No, though we did have more doctor visits and used more prescription drugs. These tend to be less costly than hospital stays, so, on balance, changes in health care use were associated with a minor reduction (2.5 percent) in health care spending.

That leaves what happens during health care visits and hospital stays (care intensity) and the price of those services and procedures.

Did we do more for patients in each health visit or inpatient stay? Did we charge more? The JAMA study found that, together, these accounted for 63 percent of the increase in spending from 1996 to 2013. In other words, most of the explanation for American health spending growth — and why it has pulled away from health spending in other countries — is that more is done for patients during hospital stays and doctor visits, they’re charged more per service, or both.

Though the JAMA study could not separate care intensity and price, other research blames prices more. For example, one study found that the spending growth for treating patients between 2003 and 2007 is almost entirely because of a growth in prices, with little contribution from growth in the quantity of treatment services provided. Another study found that U.S. hospital prices are 60 percent higher than those in Europe. Other studiesalso point to prices as a major factor in American health care spending growth.

There are ways to combat high health care prices. One is an all-payer system, like that seen in Maryland. This regulates prices so that all insurers and public programs pay the same amount. A single-payer system could also regulate prices. If attempted nationally, or even in a state, either of these would be met with resistance from all those who directly benefit from high prices, including physicians, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies — and pretty much every other provider of health care in the United States.

Higher prices aren’t all bad for consumers. They probably lead to some increased innovation, which confers benefits to patients globally. Though it’s reasonable to push back on high health care prices, there may be a limit to how far we should.