One of the things I’ve always found most fascinating about news coverage and policymaker attention to health insurers is how little focus is placed on what these companies say to their investors.

It’s no secret that each quarter, all public companies update their shareholders and provide guidance for the future. When I was at Cigna, preparing the CEO to speak with reporters and investor analysts was arguably considered the most important role I had every three months.

Mining insights from those earnings reports has been a focus of mine since I became an insurance industry whistleblower. Recently, for example, we’ve highlighted how CVS/Aetna, in particular, has taken a beating on its stock price for reporting increased spending on medical care by seniors in Medicare Advantage plans.

Now, though, CEOs have become even more public and open, beyond their quarterly earnings calls, about the challenges they are having extracting further profit from the Medicaid and Medicare programs. This should be noted, particularly by the bipartisan group of lawmakers in Washington increasingly eyeing regulatory reform on insurer practices like prior authorization, as evidence that insurers are going to become even more aggressive in limiting care to preserve their 2024 profits.

Centene’s CEO said a few days ago that medical claims are increasing in the company’s managed Medicaid business. UnitedHealth and Elevance, which owns several Blue Cross Blue Shield companies that have converted to for-profit status, also recently reported they’re seeing similar results. Combined with increased medical spending on Medicare Advantage claims, one might guess this would begin to worry investors that insurers would lower their profit forecasts.

But none of these companies have so far expressed concern about not meeting their 2024 profit expectations.

So, medical claims in Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plans – now the majority of the business for many of the largest insurers – are rising, but these companies aren’t expecting to disappoint Wall Street with a drop in profits. How is that possible?

Because insurers can deploy the tools to prevent patients from accessing care. And their playbook isn’t secret, or complicated.

By further increasing prior authorization in Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plans, insurers can limit how many seniors and low-income Americans follow through with legitimate care and procedures. (Here’s a recent congressional report on increased hurdles insurers have put in place to prevent children from receiving preventive care in Medicaid plans. And insurers’ increasing use of prior authorization in Medicare Advantage is something we’ve regularly covered.)

Unlike their marketplace and employer-based plans, insurers can’t negotiate reimbursement rates for Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plans that they manage.

But beyond prior authorization, they can put other layers of bureaucracy in place that increase how long it takes a provider to be reimbursed for providing care – and to make it more complicated for doctors to ensure they’re reimbursed fully for the care they provide.

In effect, these tactics can amount to decreasing the already industry-low rate of reimbursement for doctors from the Medicaid and Medicare Advantage programs. Physicians, you should expect to see more hurdles to reimbursement in these programs throughout the balance of 2024 as insurers look to hoard as much cash as they can.

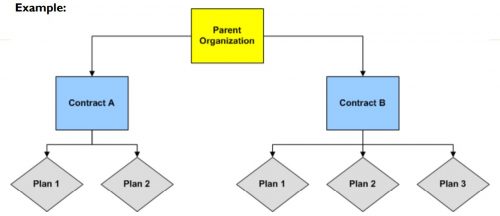

In Medicare Advantage plans, insurers can pursue the industry jargon of a “benefit buydown” to further shift costs onto plan enrollees and off insurers themselves. Because the federal government pays insurers a flat amount per Medicare Advantage enrollee, regardless of how much health care spending each patient has, it is in the insurers’ financial interest to claim that seniors and disabled people enrolled in their plans are sicker than they really are.

Rising out-of-pocket costs that seniors and disabled people in Medicare Advantage plans are facing is a consequence of insurers wanting to squeeze further profits out of the program, and is a way to maintain direct government payments per enrollee within the insurers’ coffers.