Category Archives: Underinsured

Cartoon – Modern Vows

Cartoon – Medicare Advantage

BIG INSURANCE 2023: Revenues reached $1.39 trillion thanks to taxpayer-funded Medicaid and Medicare Advantage businesses

The Affordable Care Act turned 14 on March 23. It has done a lot of good for a lot of people, but big changes in the law are urgently needed to address some very big misses and consequences I don’t believe most proponents of the law intended or expected.

At the top of the list of needed reforms: restraining the power and influence of the rapidly growing corporations that are siphoning more and more money from federal and state governments – and our personal bank accounts – to enrich their executives and shareholders.

I was among many advocates who supported the ACA’s passage, despite the law’s ultimate shortcomings. It broadened access to health insurance, both through government subsidies to help people pay their premiums and by banning prevalent industry practices that had made it impossible for millions of American families to buy coverage at any price. It’s important to remember that before the ACA, insurers routinely refused to sell policies to a third or more applicants because of a long list of “preexisting conditions” – from acne and heart disease to simply being overweight – and frequently rescinded coverage when policyholders were diagnosed with cancer and other diseases.

While insurance company executives were publicly critical of the law, they quickly took advantage of loopholes (many of which their lobbyists created) that would allow them to reap windfall profits in the years ahead – and they have, as you’ll see below.

Among other things, the ACA made it unlawful for most of us to remain uninsured (although Congress later repealed the penalty for doing so). But, notably, it did not create a “public option” to compete with private insurers, which many advocates and public policy experts contended would be essential to rein in the cost of health insurance. Many other reform advocates insisted – and still do – that improving and expanding the traditional Medicare program to cover all Americans would be more cost-effective and fair.

I wrote and spoke frequently as an industry whistleblower about what I thought Congress should know and do, perhaps most memorably in an interview with Bill Moyers. During my Congressional testimony in the months leading up to the final passage of the bill in 2010, I told lawmakers that if they passed it without a public option and acquiesced to industry demands, they might as well call it “The Health Insurance Industry Profit Protection and Enhancement Act.”

A health plan similar to Medicare that could have been a more affordable option for many of us almost happened, but at the last minute, the Senate was forced to strip the public option out of the bill at the insistence of Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Connecticut), who died on March 27, 2024. The Senate did not have a single vote to spare as the final debate on the bill was approaching, and insurance industry lobbyists knew they could kill the public option if they could get just one of the bill’s supporters to oppose it. So they turned to Lieberman, a former Democrat who was Vice President Al Gore’s running mate in 2000 and who continued to caucus with Democrats. It worked. Lieberman wouldn’t even allow a vote on the bill if it created a public option. Among Lieberman’s constituents and campaign funders were insurance company executives who lived in or around Hartford, the insurance capital of the world. Lieberman would go on to be the founding chair of a political group called No Labels, which is trying to find someone to run as a third-party presidential candidate this year.

The work of Big Insurance and its army of lobbyists paid off as insurers had hoped. The demise of the public option was a driving force behind the record profits – and CEO pay – that we see in the industry today.

The good effects of the ACA:

Nearly 49 million U.S. residents (or 16%) were uninsured in 2010. The law has helped bring that down to 25.4 million, or 8.3% (although a large and growing number of Americans are now “functionally uninsured” because of unaffordable out-of-pocket requirements, which President Biden pledged to address in his recent State of the Union speech).

The ACA also made it illegal for insurers to refuse to sell coverage to people with preexisting conditions, which even included birth defects, or charge anyone more for their coverage based on their health status; it expanded Medicaid (in all but 10 states that still refuse to cover more low-income individuals and families); it allowed young people to stay on their families’ policies until they turn 26; and it required insurers to spend at least 80% of our premiums on the health care goods and services our doctors say we need (a well-intended provision of the law that insurers have figured out how to game).

The not-so-good effects of the ACA:

As taxpayers and health care consumers, we have paid a high price in many ways as health insurance companies have transformed themselves into massive money-making machines with tentacles reaching deep into health care delivery and taxpayers’ pockets.

To make policies affordable in the individual market, for example, the government agreed to subsidize premiums for the vast majority of people seeking coverage there, meaning billions of new dollars started flowing to private insurance companies. (It also allowed insurers to charge older Americans three times as much as they charge younger people for the same coverage.) Even more tax dollars have been sent to insurers as part of the Medicaid expansion. That’s because private insurers over the years have persuaded most states to turn their Medicaid programs over to them to administer.

Insurers have bulked up incredibly quickly since the ACA was enacted through consolidation, vertical integration, and aggressive expansion into publicly financed programs – Medicare and Medicaid in particular – and the pharmacy benefit space. Premiums and out-of-pocket requirements, meanwhile, have soared.

We invite you to take a look at how the ascendency of health insurers over the past several years has made a few shareholders and executives much richer while the rest of us struggle despite – and in some cases because of – the Affordable Care Act.

BY THE NUMBERS

In 2010, we as a nation spent $2.6 trillion on health care. This year we will spend almost twice as much – an estimated $4.9 trillion, much of it out of our own pockets even with insurance.

In 2010, the average cost of a family health insurance policy through an employer was $13,710. Last year, the average was nearly $24,000, a 75% increase.

The ACA, to its credit, set an annual maximum on how much those of us with insurance have to pay before our coverage kicks in, but, at the insurance industry’s insistence, it goes up every year. When that limit went into effect in 2014, it was $12,700 for a family. This year, it has increased by 48%, to $18,900. That means insurers can get away with paying fewer claims than they once did, and many families have to empty their bank accounts when a family member gets sick or injured. Most people don’t reach that limit, but even a few hundred dollars is more than many families have on hand to cover deductibles and other out-of-pocket requirements.

Now 100 million Americans – nearly one of every three of us – are mired in medical debt, even though almost 92% of us are presumably “covered.” The coverage just isn’t as adequate as it used to be or needs to be.

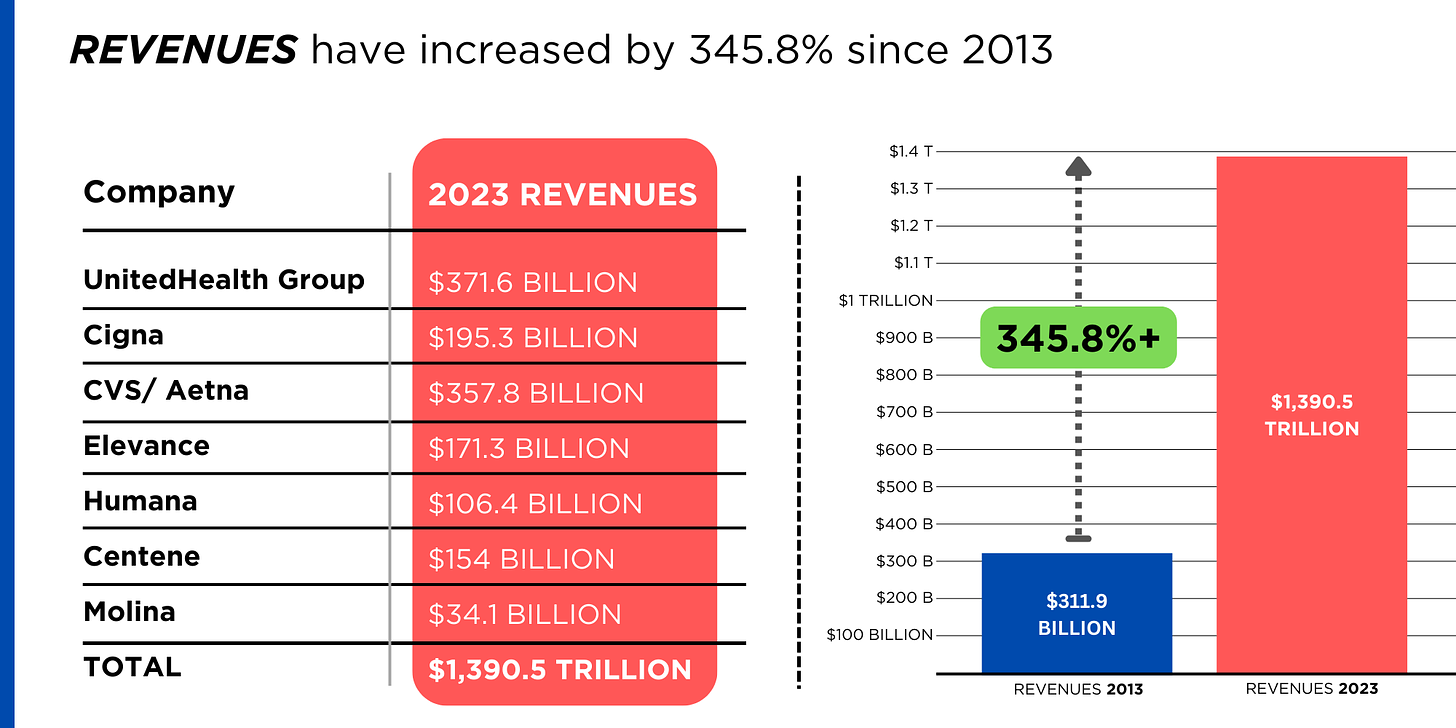

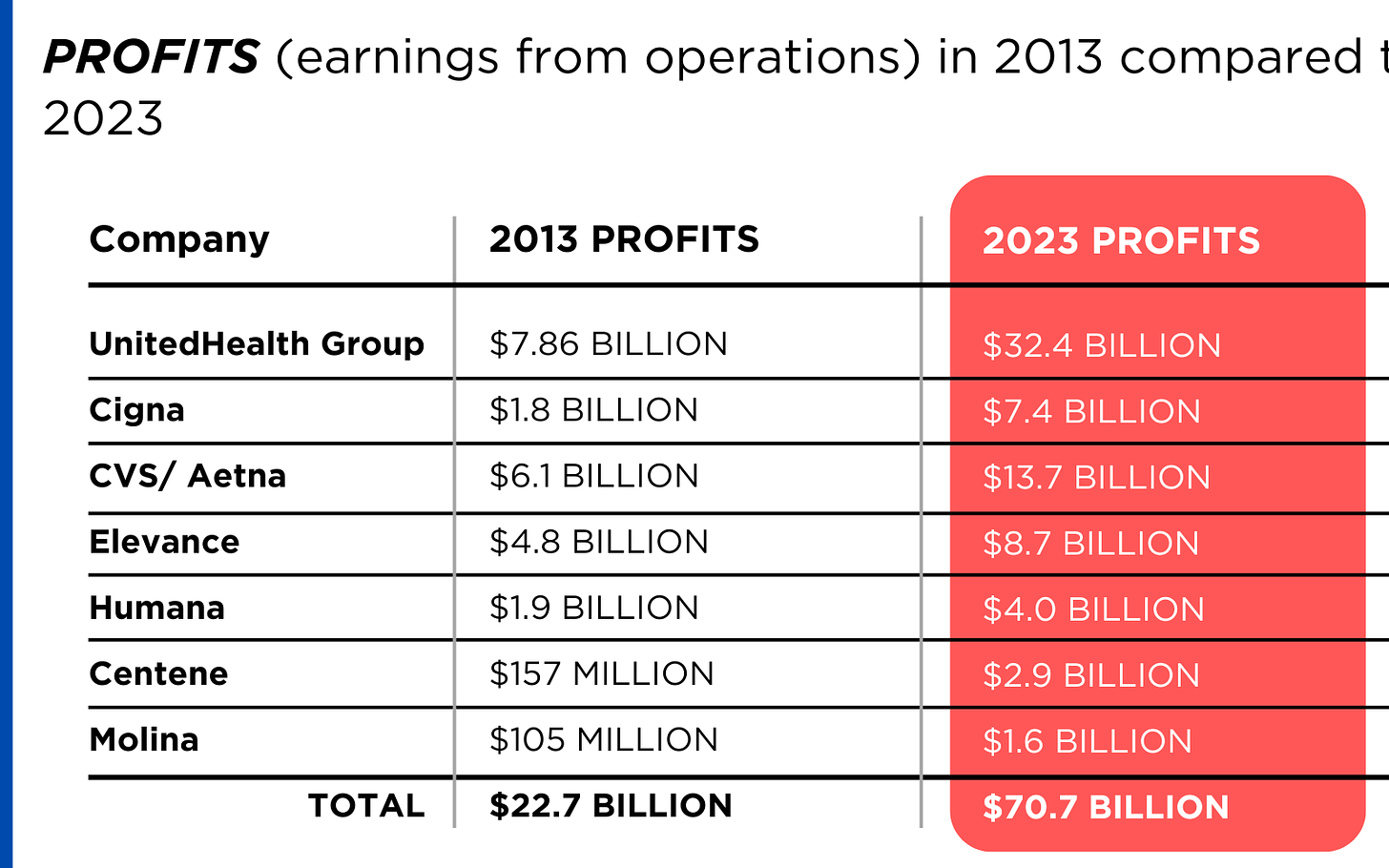

Meanwhile, insurance companies had a gangbuster 2023. The seven big for-profit U.S. health insurers’ revenues reached $1.39 trillion, and profits totaled a whopping $70.7 billion last year.

SWEEPING CHANGE, CONSOLIDATION–AND HUGE PROFITS FOR INVESTORS

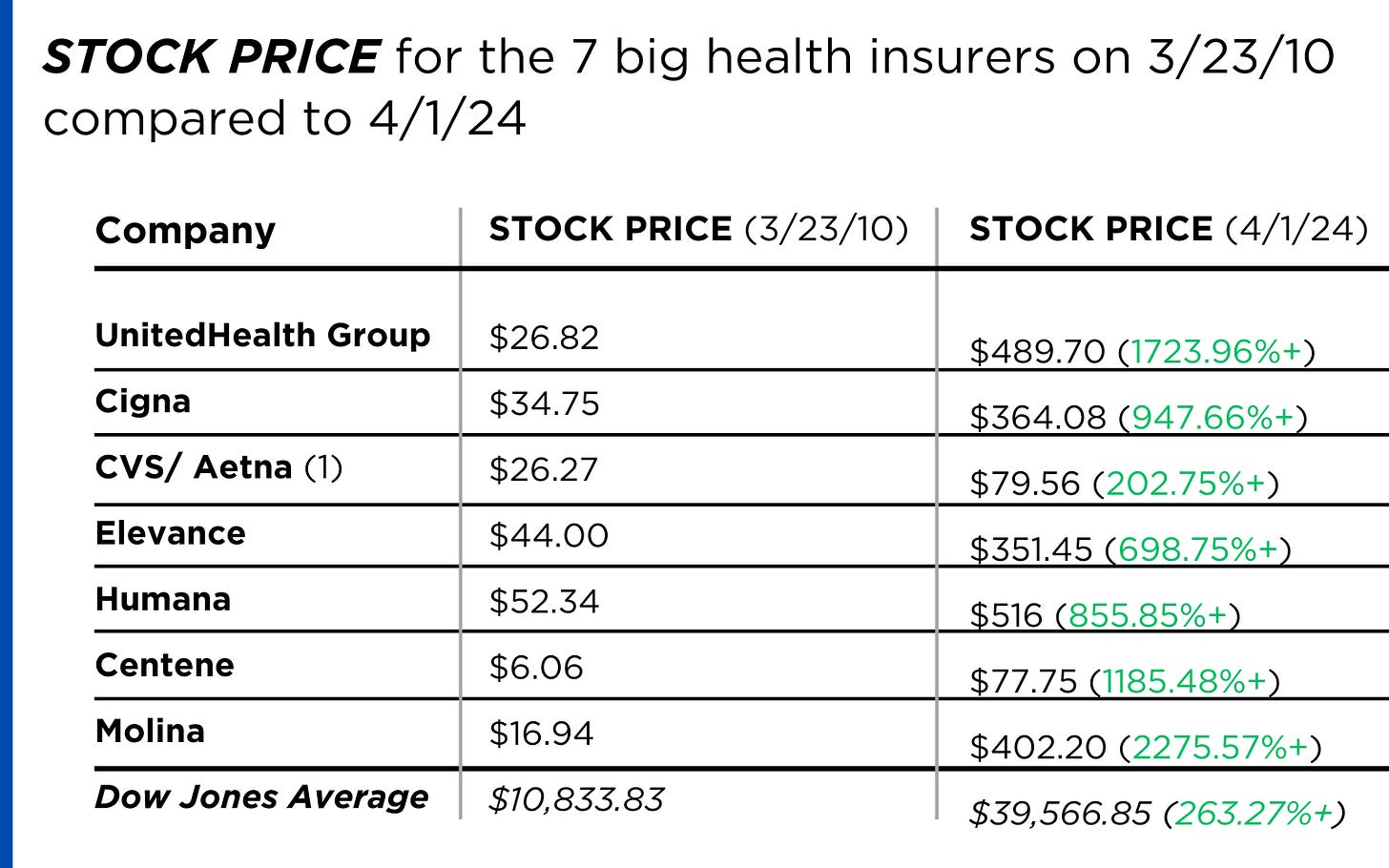

Insurance company shareholders and executives have become much wealthier as the stock prices of the seven big for-profit corporations that control the health insurance market have skyrocketed.

REVENUES collected by those seven companies have more than tripled (up 346%), increasing by more than $1 trillion in just the past ten years.

PROFITS (earnings from operations) have more than doubled (up 211%), increasing by more than $48 billion.

The CEOs of these companies are among the highest paid in the country. In 2022, the most recent year the companies have reported executive compensation, they collectively made $136.5 million.

U.S. HEALTH PLAN ENROLLMENT

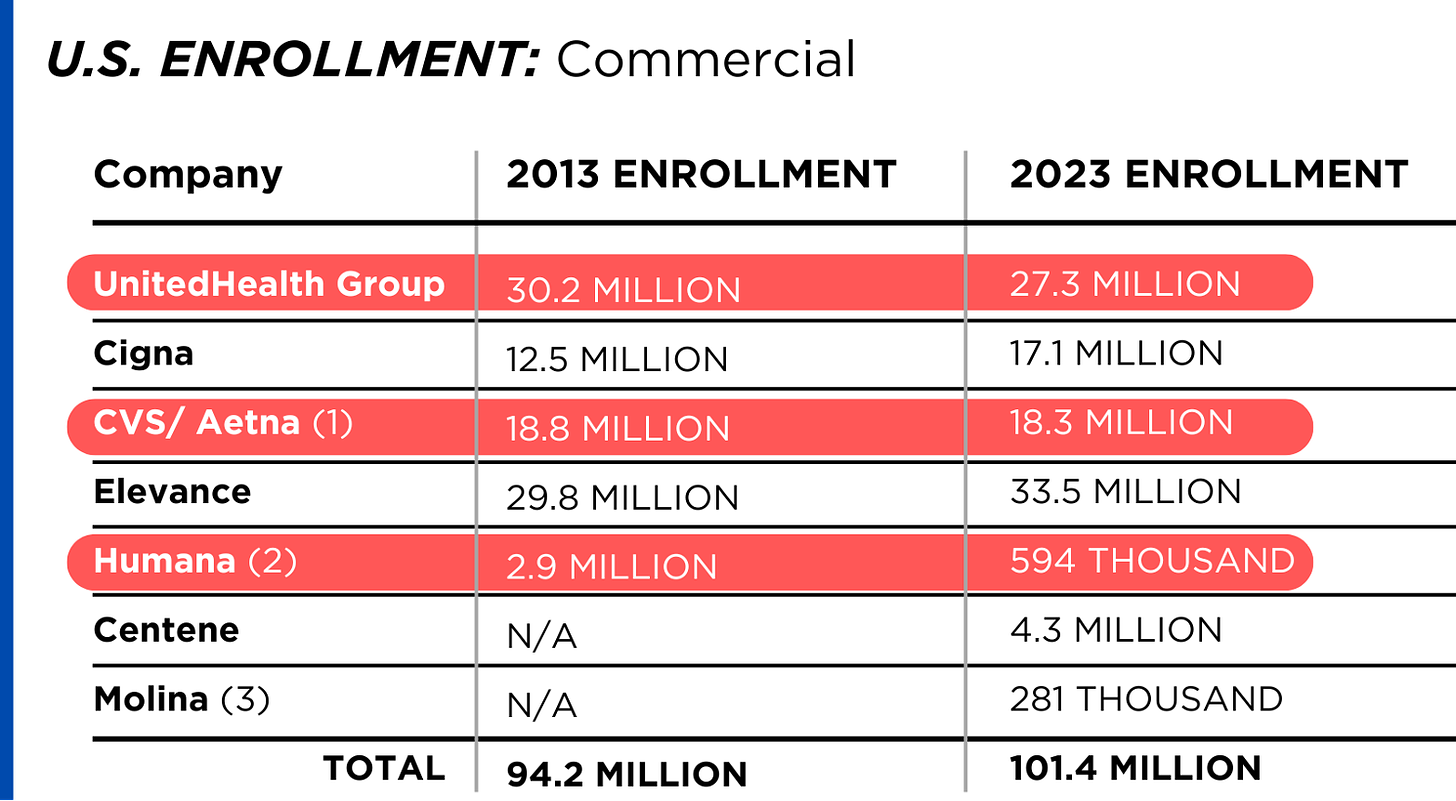

Enrollment in the companies’ health plans is a mix of “commercial” policies they sell to individuals and families and that they manage for “plan sponsors” – primarily employers and unions – and government/enrollee-financed plans (Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare for military personnel and their dependents and the Federal Employee Health Benefits program).

Enrollment in their commercial plans grew by just 7.65% over the 10 years and declined significantly at UnitedHealth, CVS/Aetna and Humana. Centene and Molina picked up commercial enrollees through their participation in several ACA (Obamacare) markets in which most enrollees qualify for federal premium subsidies paid directly to insurers.

While not growing substantially, commercial plans remain very profitable because insurers charge considerably more in premiums now than a decade ago.

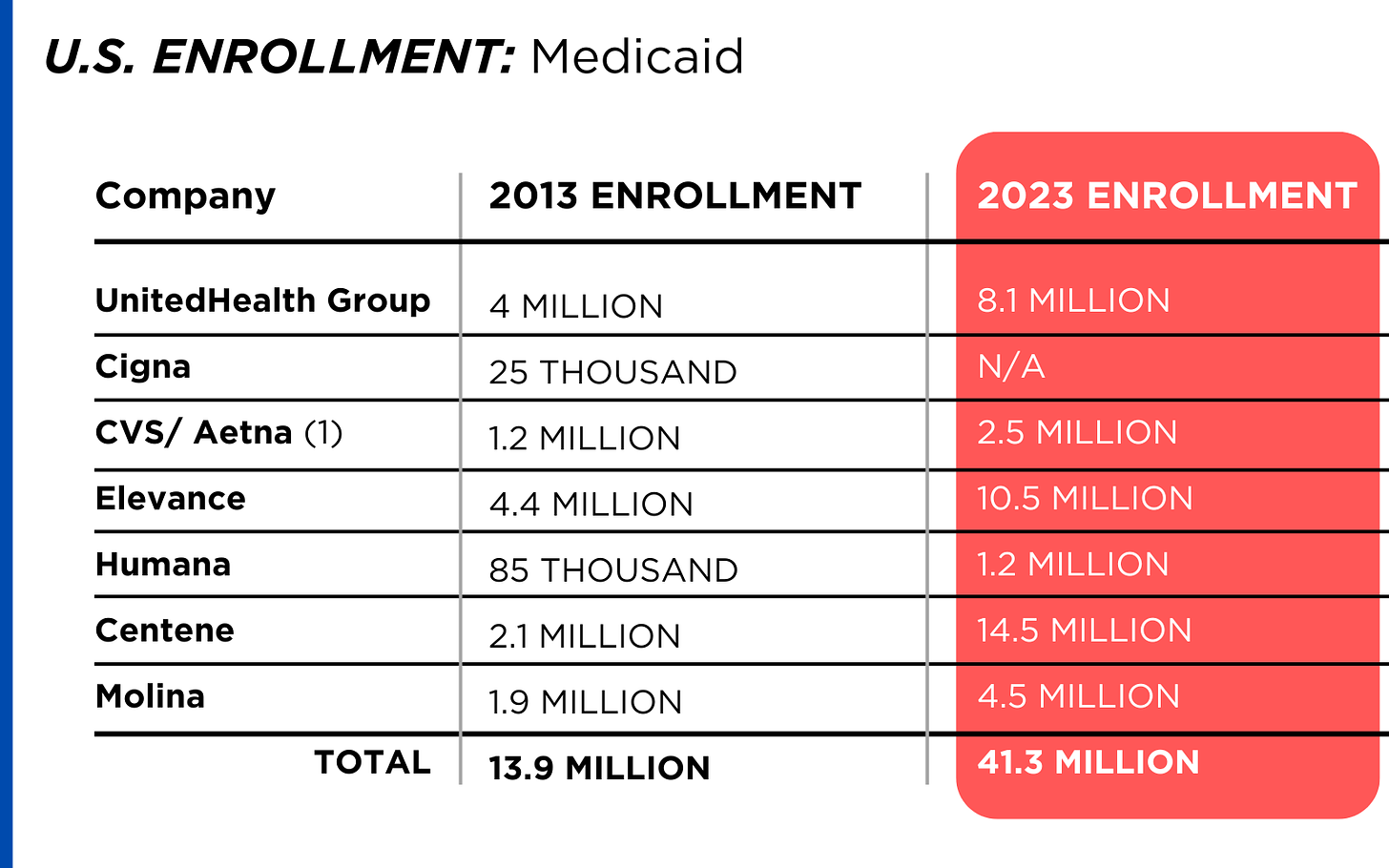

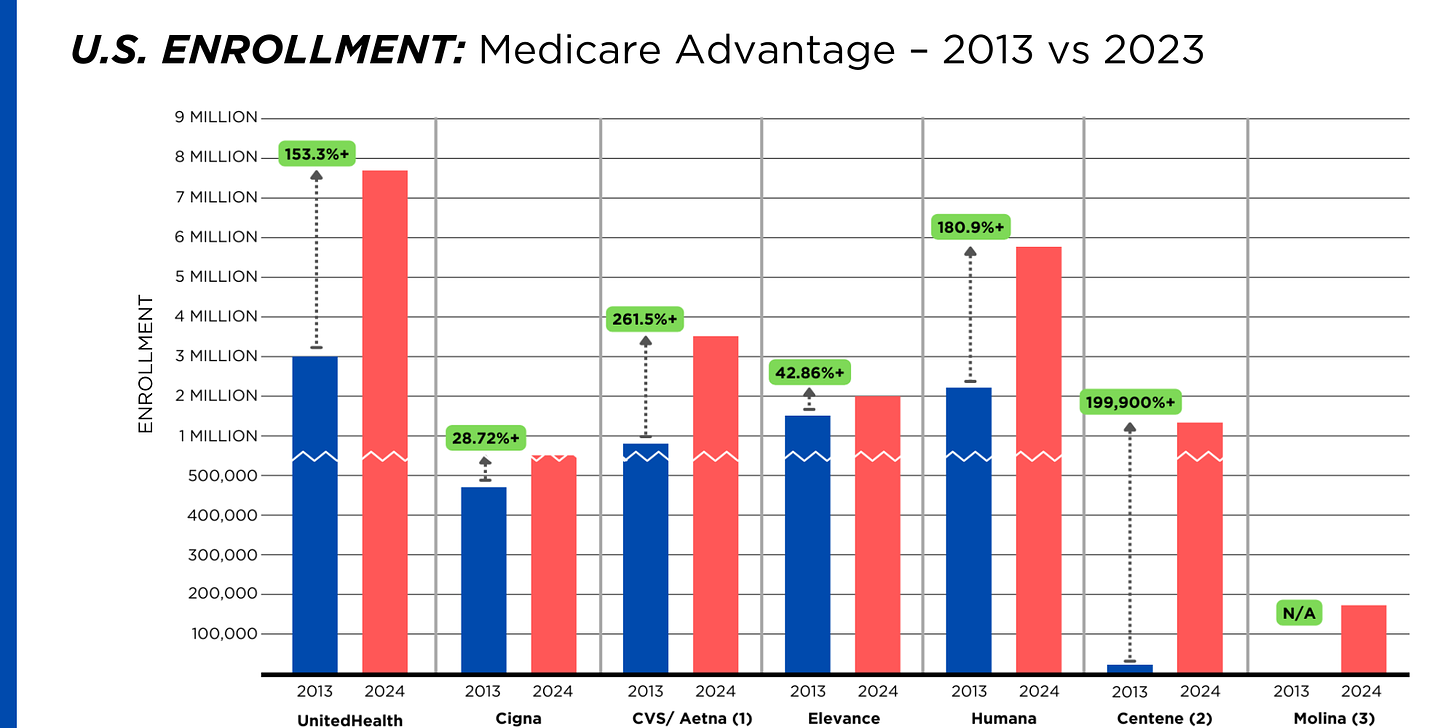

By contrast, enrollment in the government-financed Medicaid and Medicare Advantage programs has increased 197% and 167%, respectively, over the past 10 years.

Of the 65.9 million people eligible for Medicare at the beginning of 2024, 33 million, slightly more than half, enrolled in a private Medicare Advantage plan operated by either a nonprofit or for-profit health insurer, but, increasingly, three of the big for-profits grabbed most new enrollees. Of the 1.7 million new Medicare Advantage enrollees this year, 86% were captured by UnitedHealth, Humana and Aetna. Those three companies are the leaders in the Medicare Advantage business among the for-profit companies, and, according to the health care consulting firm Chartis, are taking over the program “at breakneck speed.”

It is worth noting that although four companies saw growth in their Medicare Supplement enrollment over the decade, enrollment in Medicare Supplement policies has been declining in more recent years as insurers have attracted more seniors and disabled people into their Medicare Advantage plans.

OTHER FEDERAL PROGRAMS

In addition to the above categories, Humana and Centene have significant enrollment in Tricare, the government-financed program for the military. Humana reported 6 million military enrollees in 2023, up from 3.1 million in 2013. Centene reported 2.8 million in 2023. It did not report any military enrollment in 2013.

Elevance reported having 1.6 million enrollees in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program in 2023, up from 1.5 million in 2013. That total is included in the commercial enrollment category above.

PBMs

As with Medicare Advantage, three of the big seven insurers control the lion’s share of the pharmacy benefit market (and two of them, UnitedHealth and CVS/Aetna, are also among the top three in signing up new Medicare Advantage enrollees, as noted above). CVS/Aetna’s Caremark, Cigna’s Express Scripts and UnitedHealth’s Optum Rx PBMs now control 80% of the market.

At Cigna, Express Scripts’ pharmacy operations now contribute more than 70% to the company’s total revenues. Caremark’s pharmacy operations contribute 33% to CVS/Aetna’s total revenues, and Optum Rx contributes 31% to UnitedHealth’s total revenues.

WHAT TO DO AND WHERE TO START

The official name of the ACA is the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The law did indeed implement many important patient protections, and it made coverage more affordable for many Americans. But there is much more Congress and regulators must do to close the loopholes and dismantle the barriers erected by big insurers that enable them to pad their bottom lines and reward shareholders while making health care increasingly unaffordable and inaccessible for many of us.

Several bipartisan bills have been introduced in Congress to change how big insurers do business.

They include curbing insurers’ use of prior authorization, which often leads to denials and delays of care; requiring PBMs to be more “transparent” in how they do business and banning practices many PBMs use to boost profits, including spread pricing, which contributes to windfall profits; and overhauling the Medicare Advantage program by instituting a broad array of consumer and patient protections and eliminating the massive overpayments to insurers.

And as noted above, President Biden has asked Congress to broaden the recently enacted $2,000-a-year cap on prescription drugs to apply to people with private insurance, not just Medicare beneficiaries. That one policy change could save an untold number of lives and help keep millions of families out of medical debt. (A coalition of more than 70 organizations and businesses, which I lead, supports that, although we’re also calling on Congress to reduce the current overall annual out-of-pocket maximum to no more than $5,000.)

I encourage you to tell your members of Congress and the Biden administration that you support these reforms as well as improving, strengthening and expanding traditional Medicare. You can be certain the insurance industry and its allies are trying to keep any reforms that might shrink profit margins from becoming law.

Healthcare Spending 2000-2022: Key Trends, Five Important Questions

Last week, Congress avoided a partial federal shutdown by passing a stop-gap spending bill and now faces March 8 and March 22 deadlines for authorizations including key healthcare programs.

This week, lawmakers’ political antenna will be directed at Super Tuesday GOP Presidential Primary results which prognosticators predict sets the stage for the Biden-Trump re-match in November. And President Biden will deliver his 3rd State of the Union Address Thursday in which he is certain to tout the economy’s post-pandemic strength and recovery.

The common denominator of these activities in Congress is their short-term focus: a longer-term view about the direction of the country, its priorities and its funding is not on its radar anytime soon.

The healthcare system, which is nation’s biggest employer and 17.3% of its GDP, suffers from neglect as a result of chronic near-sightedness by its elected officials. A retrospective about its funding should prompt Congress to prepare otherwise.

U.S. Healthcare Spending 2000-2022

Year-over-year changes in U.S. healthcare spending reflect shifting demand for services and their underlying costs, changes in the healthiness of the population and the regulatory framework in which the U.S. health system operates to receive payments. Fluctuations are apparent year-to-year, but a multiyear retrospective on health spending is necessary to a longer-term view of its future.

The period from 2000 to 2022 (the last year for which U.S. spending data is available) spans two economic downturns (2008–2010 and 2020–2021); four presidencies; shifts in the composition of Congress, the Supreme Court, state legislatures and governors’ offices; and the passage of two major healthcare laws (the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and the Affordable Care Act of 2010).

During this span of time, there were notable changes in healthcare spending:

- In 2000, national health expenditures were $1.4 trillion (13.3% of gross domestic product); in 2022, they were $4.5 trillion (17.3% of the GDP)—a 4.1% increase overall, a 321% increase in nominal spending and a 30% increase in the relative percentage of the nation’s GDP devoted to healthcare. No other sector in the economy has increased as much.

- In the same period, the population increased 17% from 282 million to 333 million, per capita healthcare spending increased 178% from $4,845 to $13,493 due primarily to inflation-impacted higher unit costs for , facilities, technologies and specialty provider costs and increased utilization by consumers due to escalating chronic diseases.

- There were notable changes where dollars were spent: Hospitals remained relatively unchanged (from $415 billion/30.4% of total spending to $1.355 trillion/31.4%), physician services shrank (from $288.2 billion/21.1% to $884.8/19.6%) and prescription drugs were unchanged (from $122.3 billion/8.95% to $405.9 billion/9.0%).

- And significant changes in funding Out-of-pocket shrank from 14.2% ($193.6 billion in 2020) to (10.5% ($471 billion) in 2020, private insurance shrank from $441 billion/32.3% to $1.289 trillion/29%, Medicare spending grew from $224.8 billion/16.5% to $944.3billion/21%; Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program spending grew from $203.4 billion/14.9% to $7805.7billion/18%; and Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare spending grew from $19.1 billion/1.4% to $98 billion/2.2%.

Looking ahead (2022-2031), CMS forecasts average National Health Expenditures (NHE) will grow at 5.4% per year outpacing average GDP growth (4.6%) and resulting in an increase in the health spending share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 17.3% in 2021 to 19.6% in 2031.

The agency’s actuaries assume

“The insured share of the population is projected to reach a historic high of 92.3% in 2022… Medicaid enrollment will decline from its 2022 peak of 90.4M to 81.1M by 2025 as states disenroll beneficiaries no longer eligible for coverage. By 2031, the insured share of the population is projected to be 90.5 percent. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is projected to result in lower out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs for 2024 and beyond as Medicare beneficiaries incur savings associated with several provisions from the legislation including the $2,000 annual out-of-pocket spending cap and lower gross prices resulting from negotiations with manufacturers.”

My take:

The reality is this: no one knows for sure what the U.S. health economy will be in 2025 much less 2035 and beyond. There are too many moving parts, too much invested capital seeking near-term profits, too many compensation packages tied to near-term profits, too many unknowns like the impact of artificial intelligence and court decisions about consolidation and too much political risk for state and federal politicians to change anything.

One trend stands out in the data from 2000-2022: The healthcare economy is increasingly dependent on indirect funding by taxpayers and less dependent on direct payments by users.

In the last 22 years, local, state and federal government programs like Medicare, Medicaid and others have become the major sources of funding to the system while direct payments by consumers and employers, vis-à-vis premium out-of-pocket costs, increased nominally but not at the same rate as government programs. And total spending has increased more than the overall economy (GDP), household wages and costs of living almost every year.

Thus, given the trends, five questions must be addressed in the context of the system’s long-term solvency and effectiveness looking to 2031 and beyond:

- Should its total spending and public funding be capped?

- Should the allocation of funds be better adapted to innovations in technology and clinical evidence?

- Should the financing and delivery of health services be integrated to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the system?

- Should its structure be a dual public-private system akin to public-private designations in education?

- Should consumers play a more direct role in its oversight and funding?

Answers will not be forthcoming in Campaign 2024 despite the growing significance of healthcare in the minds of voters. But they require attention now despite political neglect.

PS: The month of February might be remembered as the month two stalwarts in the industry faced troubles:

United HealthGroup, the biggest health insurer, saw fallout from a cyberattack against its recently acquired (2/22) insurance transaction processor by ALPHV/Blackcat, creating havoc for the 6000 hospitals, 1 million physicians, and 39,000 pharmacies seeking payments and/or authorizations. Then, news circulated about the DOJ’s investigation about its anti-competitive behavior with respect to the 90,000 physicians it employs. Its stock price ended the week at 489.53, down from 507.14 February 1.

And HCA, the biggest hospital operator, faced continued fallout from lawsuits for its handling of Mission Health (Asheville) where last Tuesday, a North Carolina federal court refused to dismiss a lawsuit accusing it of scheming to restrict competition and artificially drive-up costs for health plans. closed at 311.59 last week, down from 314.66 February 1.

The Three In-bound Truth Bombs set to Explode in U.S. Healthcare

In Sunday’s Axios’ AM, Mike Allen observed “Republicans know immigration alone could sink Biden. So, Trump and House Republicans will kill anything, even if it meets or exceeds their wishes. Biden knows immigration alone could sink him. So he’s willing to accept what he once considered unacceptable — to save himself.”

Mike called this a “truth Bomb” and he’s probably right: the polarizing issue of immigration is tantamount to a bomb falling on the political system forcing well-entrenched factions to re-think and alter their strategies.

In 2024, in U.S. healthcare, three truth bombs are in-bound. They’re the culmination of shifts in the U.S.’ economic, demographic, social and political environment and fueled by accelerants in social media and Big Data.

Truth bomb: The regulatory protections that have buoyed the industry’s growth are no longer secure.

Despite years of effectively lobbying for protections and money, the industry’s major trade groups face increasingly hostile audiences in city hall, state houses and the U.S. Congress.

The focus of these: the business practices that regulators think protect the status quo at the public’s expense. Example: while the U.S. House spent last week in their districts, Senate Committees held high profile hearings about Medicare Advantage marketing tactics (Finance Committee), consumer protections in assisted living (Special Committee on Aging), drug addiction and the opioid misuse (Banking) and drug pricing (HELP). In states, legislators are rationalizing budgets for Medicaid and public health against education, crime and cybersecurity and lifting scope of practice constraints that limit access.

Drug makers face challenges to patents (“march in rights”) and state-imposed price controls. The FTC and DOJ are challenging hospital consolidation they think potentially harmful to consumer choice and so. Regulators and lawmakers are less receptive to sector-specific wish lists and more supportive of populist-popular rules that advance transparency, disable business relationships that limit consumer choices and cede more control to individuals. Given that the industry is built on a business-to-business (B2B) chassis, preparing for a business to consumer (B2C) time bomb will be uncomfortable for most.

Truth bomb: Affordability in U.S. is not its priority.

The Patient Protection and Affordability Act 2010 advanced the notion that annual healthcare spending growth should not exceed more than 1% of the annual GDP. It also advanced the premise that spending should not exceed 9.5% of household adjusted gross income (AGI) and associated affordability with access to insurance coverage offering subsidies and Medicaid expansion incentives to achieve near-universal coverage. In 2024, that percentage is 8.39%.

Like many elements of the ACA, these constructs fell short: coverage became its focus; affordability secondary.

The ranks of the uninsured shrank to 9% even as annual aggregate spending increased more than 4%/year. But employers and privately insured individuals saw their costs increase at a double-digit pace: in the process, 41% of the U.S. population now have unpaid medical debt: 45% of these have income above $90,000 and 61% have health insurance coverage. As it turns out, having insurance is no panacea for affordability: premiums increase just as hospital, drug and other costs increase and many lower- and middle-income consumers opt for high-deductible plans that expose them to financial insecurity. While lowering spending through value-based purchasing and alternative payments have shown promise, medical inflation in the healthcare supply chain, unrestricted pricing in many sectors, the influx of private equity investing seeking profit maximization for their GPs, and dependence on high-deductible insurance coverage have negated affordability gains for consumers and increasingly employers. Benign neglect for affordability is seemingly hardwired in the system psyche, more aligned with soundbites than substance.

Truth bomb: The effectiveness of the system is overblown.

Numerous peer reviewed studies have quantified clinical and administrative flaws in the system. For instance, a recent peer reviewed analysis in the British Medical Journal concluded “An estimated 795 000 Americans become permanently disabled or die annually across care settings because dangerous diseases are misdiagnosed. Just 15 diseases account for about 50.7% of all serious harms, so the problem may be more tractable than previously imagined.”

The inadequacy of personnel and funding in primary and preventive health services is well-documented as the administrative burden of the system—almost 20% of its spending. Satisfaction is low. Outcomes are impressive for hard-to-diagnose and treat conditions but modest at best for routine care. It’s easier to talk about value than define and measure it in our system: that allows everyone to declare their value propositions without challenge.

Truth bombs are falling in U.S. healthcare. They’re well-documented and financed. They take no prisoners and exact mass casualties.

Most healthcare organizations default to comfortable defenses. That’s not enough. Cyberwarfare, precision-guided drones and dirty bombs require a modernized defense. Lacking that, the system will be a commoditized public utility for most in 15 years.

PS: Last week’s report, “The Holy War between Hospitals and Insurers…” (The Keckley Report – Paul Keckley) prompted understandable frustration from hospitals that believe insurers do not serve the public good at a level commensurate with the advantages they enjoy in the industry. However, justified, pushback by hospitals against insurers should be framed in the longer-term context of the role and scope of services each should play in the system long-term. There are good people in both sectors attempting to serve the public good. It’s not about bad people; it’s about a flawed system.

ACA enrollment continues at a record pace

https://nxslink.thehill.com/view/6230d94bc22ca34bdd8447c8k3p6r.11v6/ce256994

Affordable Care Act (ACA) enrollment appears poised to reach record levels once again as signups grew by more than a third of what they were this time last year, a fact the White House is using to continue to draw attention to former President Trump’s threats to try again to repeal the law.

More than 15 million people have signed up for plans in states that use HealthCare.gov, representing a 33 percent increase from last year. The Biden administration estimates 19 million will sign up for plans by the Jan. 16 deadline.

On Dec. 15, the deadline for coverage starting Jan. 1, more than 745,000 people selected a plan through HealthCare.gov — the most in a day in history, the Department of Health and Human Services said.

For 2023 plans, more than 16.3 million people signed up through HealthCare.gov last year, another record. Of those who enrolled for this year, 22 percent were new to the marketplace.

This year’s enrollment had some unusual factors that may have played a part in boosting enrollment. Those who were disenrolled from Medicaid this year during the “unwinding” period were allowed to sign up for ACA plans earlier than normal.

There was also stronger insurer participation in the program this year, providing significantly more options for customers to choose from.

“Thanks to policies I signed into law, millions of Americans are saving hundreds or thousands of dollars on health insurance premiums,” President Biden said on Wednesday.

“Extreme Republicans want to stop these efforts in their tracks,” he added. “At every turn, extreme Republicans continue to side with special interests to keep prescription drug prices high and to deny millions of people health coverage.”

Cartoon – Dying of Status Quo

The US doesn’t have universal health care — but these states (almost) do

https://www.vox.com/policy/23972827/us-aca-enrollment-universal-health-insurance

Ten states have uninsured rates below 5 percent. What are they doing right?

Universal health care remains an unrealized dream for the United States. But in some parts of the country, the dream has drawn closer to a reality in the 13 years since the Affordable Care Act passed.

Overall, the number of uninsured Americans has fallen from 46.5 million in 2010, the year President Barack Obama signed his signature health care law, to about 26 million today. The US health system still has plenty of flaws — beyond the 8 percent of the population who are uninsured, far higher than in peer countries, many of the people who technically have health insurance still find it difficult to cover their share of their medical bills. Nevertheless, more people enjoy some financial protection against health care expenses than in any previous period in US history.

The country is inching toward universal coverage. If everybody who qualified for either the ACA’s financial assistance or its Medicaid expansion were successfully enrolled in the program, we would get closer still: More than half of the uninsured are technically eligible for government health care aid.

Particularly in the last few years, it has been the states, using the tools made available by them by the ACA, that have been chipping away most aggressively at the number of uninsured.

Today, 10 states have an uninsured rate below 5 percent — not quite universal coverage, but getting close. Other states may be hovering around the national average, but that still represents a dramatic improvement from the pre-ACA reality: In New Mexico, for instance, 23 percent of its population was uninsured in 2010; now just 8 percent is.

Their success indicates that, even without another major federal health care reform effort, it is possible to reduce the number of uninsured in the United States. If states are more aggressive about using all of the tools available to them under the ACA, the country could continue to bring down the number of uninsured people within its borders.

The law gave states discretion to build upon its basic structure. Many received approval from the federal government to create programs that lower premiums; some also offer state subsidies in addition to the federal assistance to reduce the cost of coverage, including for people who are not eligible for federal aid, such as undocumented immigrants. A few states are even offering new state-run health plans that will compete with private offerings.

I asked several leading health care experts which states stood out to them as having fully weaponized the ACA to reduce the number of uninsured. There was not a single answer.

“I don’t think any state has taken advantage of everything,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president at the KFF health policy think tank. “No state has put all the pieces together to the full extent available under the ACA.”

But a few stood out for the steps they have taken over the last decade to strive toward universal health care.

Massachusetts (and New Mexico): Streamlined enrollment and state subsidies

Massachusetts has the lowest uninsured rate of any state: Just 2.4 percent of the population lacks coverage. It had a head start: The law provided the model for the ACA itself, with its system of government subsidies for private plans sold on a public marketplace that existed prior to 2010.

But experts say it still deserves credit for the steps it has taken since the Massachusetts model was applied to the rest of the country. Matt Fiedler, a senior fellow with the Brookings Schaeffer Initiative on Health Policy, said two policies stood above any others in expanding coverage: integrating the enrollment process for both Medicaid and ACA marketplace plans and offering state-based assistance on top of the law’s federal subsidies.

Massachusetts was among the first states to do both.

“The former can do a lot to reduce the risk that people lose their coverage when incomes change,” Fiedler told me, “while the latter directly improves affordability and thereby promotes take-up.”

Integrated enrollment means that, for the consumer, they can be directed to either the ACA’s marketplace (where they can use government subsidies to buy private coverage) or to the state Medicaid program through one portal. They enter their information and the state tells them which program they should enroll in. Without that integration, people might have to first apply to Medicaid and then, if they don’t qualify, separately seek out marketplace coverage. The more steps that a person must take to successfully enroll in a health plan, the more likely it is people will fall through the cracks.

The state assistance, meanwhile, both reduces premiums for people and makes it easier for them to afford more generous coverage, with lower out-of-pocket costs when they actually use medical services. Nine states including Massachusetts now have state assistance, with interest picking up in the past few years.

New Mexico, for example, only recently converted to a state-based ACA marketplace and started offering additional aid in 2023. Having already seen some dramatic improvements, it remains to be seen how much more progress the state can make toward universal coverage with that policy in place.

Minnesota and New York: The Basic Health Plan states

The basic structure of the ACA was this: Medicaid expansion for people living in or near poverty and marketplace plans for people with incomes above that. But the law included an option for states to more seamlessly integrate those two populations — and so far, the two states that have taken advantage of it, Minnesota and New York, are also among those states with the lowest uninsured rates. Just 4.3 percent of Minnesotans and 4.9 percent of New Yorkers lack coverage today.

They have both created Basic Health Plans, the product of one of the more obscure provisions of the health care law. This is a state-regulated health insurance plan meant to cover people up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level (about $29,000 for an individual or $50,000 for a family of three). Those are people who may not technically qualify for Medicaid under the ACA but who can still struggle to afford their monthly premiums and out-of-pocket obligations with a marketplace plan.

In both states, the Basic Health Plans offered insurance options with lower premiums and reduced cost-sharing responsibilities than the marketplace coverage that they would otherwise have been left with. In New York, for example, people between 100 percent and 150 percent of the federal poverty level pay no premiums at all, while people between 150 percent and 200 percent pay just $20 per month.

There is good evidence that the approach has increased coverage: In New York, for example, enrollment among people below 200 percent of the poverty level increased by 42 percent when the state adopted its BHP in 2016, compared to what it had been the year before when those people were relegated to conventional marketplace coverage.

State interest in Basic Health Plans has been limited so far, but Minnesota and New York provide a model others could follow. Fiedler said part of the basic plans’ success in those states has been using Medicaid managed-care companies to administer the plan: Those insurers already pay providers lower rates than marketplace plans do and the savings give the states money to reduce premiums and cost-sharing.

Colorado and Washington: Public options and assistance for the undocumented

These states have been inventive in myriad ways. They are both early adopters of a public option, a government health plan that competes with private plans on the marketplace, a policy also being tested in Nevada.

There is another policy that unites them, one that addresses a sizable part of the remaining uninsured nationwide: They both provide some state subsidies to undocumented immigrants.

Most uninsured Americans are already technically eligible for some kind of government assistance, whether Medicaid or marketplace subsidies. But there is a large chunk of people who are not: About 29 percent of the US’s uninsured are ineligible for government aid, among them the people who are in the country undocumented. Those people bear the full cost of their medical bills and may avoid care for that reason (among others, of course).

Starting this year, Washington is allowing undocumented people with incomes that would make them eligible for Medicaid expansion to enroll in that program, and making state subsidies available to people with higher incomes no matter their immigration status. Colorado has set aside a small pool of money annually to provide state aid to about 11,000 undocumented people. (After that threshold is hit, those folks can still enroll in a health plan but they must pay the full price.)

Interest has been robust: Last year, Colorado hit the enrollment limit after about a month. This year, enrollment capped out in just two days, suggesting the state may need to put more money behind the effort.

It is difficult to imagine insurance subsidies for undocumented people nationwide any time soon, given the fraught national politics of immigration. But states are finding ways to make inroads on their own: California has made undocumented people eligible for Medicaid.

Through these and other means, they are helping the US inch toward universal health care.