Segment 8 – Applying Our Values & Philosophy to Healthcare Reform

This segment reviews traditional American values and philosophical principles that can help resolve the core dilemma that has stopped us from fixing US healthcare for years – the unresolved conflict between “social justice” and “market justice.”

In the first six Segments, we reviewed the relentless growth of healthcare spending. And how rising costs are literally built into the system as it is now.

In Segment 7 we talked about some landmines that lurk beneath the surface of fixing healthcare – power and politics.

In this Segment, we will look at traditional American values and at philosophical principles that can help us resolve the core dilemma that has stopped us from fixing US healthcare all these years.

Let’s start with the American traditions. Some of these have been a bit romanticized in our imagination. So we’ll look at each of them in more detail.

Freedom of the individual is pretty clear. It brings to mind the pioneer spirit of early adventurers and settlers.

There is a presumption for rugged individualism and against government entanglement. But even by the time of the Revolutionary War and Constitutional Convention growing colonial cities were developing governmental and civic services like fire departments and sanitation programs.

Free enterprise is a core American value. But here again, there are examples from earliest Colonial days of collective projects, such as the Boston Commons, schools, and toll roads that stood alongside freestanding farms and shops.

Next is “Yankee ingenuity.” Americans are entrepreneurs, innovators, practical problem solvers. We have never been bound by tired old ideas from Europe or elsewhere. We come up with our own ideas and forge ahead with progress. We’ll come back to these concepts.

There is an American tradition to distrust government. But if we look more closely at what this meant to the Founding Fathers, it was not government itself that they distrusted. In fact, Americans never embraced anarchy; they always set up orderly civic structures in every settlement and colony. What they abhorred was tyranny, the concentration of power in the hands of a sometimes capricious and self-serving autocrat. Further, they distrusted any individual person wielding authority. And so the Constitutional Framers crafted a government with the right balance between too much and too little authority, separate branches, and checks and balances. Today’s institutions – including healthcare – will do well to build in the same kind of accountability, transparency and checks and balances, especially since so much money and power is involved.

And so I am going to rename this tradition, Distrust of Tyranny (and of Human Fallibility).

Lastly is our tradition to protect under the law outcasts, the weak, and the vulnerable. Colonial settlers were often themselves oddballs or failures, seeking the opportunity for a new life in America. They enshrined protections for themselves in law, notably the Bill of Rights.

Since a large group of Americans today express misgivings that government involvement in healthcare would be a betrayal of our Founding traditions, I would like to offer several more reflections.

Look at the principles listed in the Declaration of Independence and the Preamble to the Constitution – life, liberty and pursuit of happiness.

More perfect union, justice, domestic tranquility, general welfare, and the blessings brought by liberty to ourselves and our posterity. These sound to me like values that would flow from a people who don’t worry about getting care when they become sick, and who willingly embrace practical healthcare reforms that advance the common good. This is a far cry from the notion that the Framers would have wanted to freeze us into their time – 1788, to be exact. I have a feeling that the Founding Fathers were too practical minded, ingenious and adaptable to lock themselves into even their own ideas. Rather, I think they would try to honor American traditions, compromise over seemingly different viewpoints, seek solutions that bring us together and bind us together, promote the common good, and maximize our freedom, wellbeing (or “welfare,” to use their terminology), and stewardship of our great blessings.

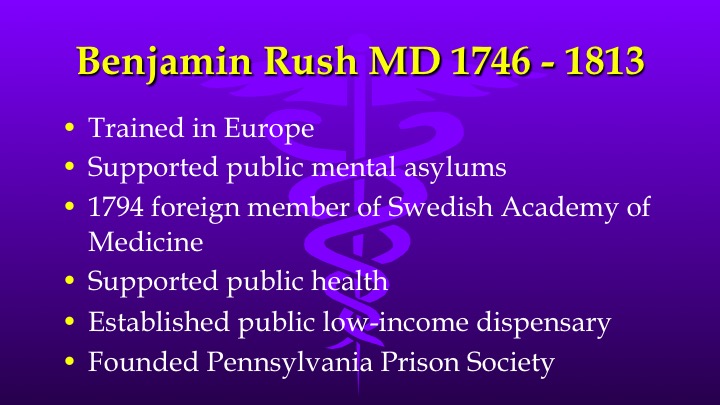

Not to belabor this point, but I’d like to look back at Dr. Benjamin Rush, who we met in Segment 2 as a prominent doctor in the Revolutionary period who signed the Declaration of Independence. Recollect that he received his medical training at University of Edinburgh, the foremost medical school of that time, which in the European system was state-run. He supported publicly-funded mental asylums and is considered to be the father of American psychiatry. In 1794 he was inducted as a foreign member of Swedish Academy of Medicine, which is the historic root of Sweden’s modern-day national healthcare system. Rush supported public health and sanitation initiatives, such as rerouting Dock Creek and draining its surrounding swamp on the east side of Philadelphia to eliminate mosquito breeding grounds. He established a public dispensary for low income patients. And he founded the Pennsylvania Prison Society to protect rights of prisoners and promote their humane treatment.

Based on this profile, I don’t think it’s a stretch to believe that this 18th century Founding Father might support innovative public and private partnerships ensuring healthcare for all citizens if a time machine could transport him into the 21st century.

Now let’s now look at what some healthcare philosophers in this century say about fair ways to run the system. The basic principles of healthcare ethics are autonomy (which is self-determination), justice (fair distribution of costs and benefits), beneficence (the most good for all), and professional integrity (meaning that society has a stake in the independence of doctors).

One philosopher who has applied these principles to modern healthcare is Paul Menzel from Pacific Lutheran University in Washington state.

He has been writing on the ethics of the healthcare system since 1983, when he came to Washington DC to apply his philosopher’s methodology to the issue, until his retirement in 2012. Here are his view of the features of a fair system of healthcare delivery and financing.

- The system should provide costworthy care, and costworthy care only, no wasteful treatments.

- The system should provide financial protection to sick individuals who need care.

- The system should make health care equitably accessible to all.

- The system should equitably distribute the costs of care between the ill and the well

- The system should justly allocate the costs of care between the rich and the poor.

- The system should respect autonomy of patient choice.

- The system should respect provider choice.

Two other philosophers, one an ethicist and the other a doctor, have laid out fair, publicly acceptable ways to set limits on healthcare spending. There needs to be:

- Open, transparent deliberations

- Use of relevant criteria agreed on by all

- An appeals procedures for individual extenuating cases.

- Uniform standards and regulations applying to all delivery and financing systems.

Let’s end on a key philosophical controversy in the US – market justice versus social justice. Market justice means, in starkest form, that consumers can buy only what they can afford, and that giving them something they have not earned is ethically and economically wrong. Social justice sees equitable distribution of health-care as a societal responsibility, without regard to ability to pay. (Note that I am purposely avoiding the loaded words – “rights” and “privileges,” which tend to inflame this controversy.)

It has been said that progress on healthcare reform is stymied by our country’s inability to choose one or the other – we’ve been caught between the two ideas of justice.

In the next Segment I will ask whether the two sides of the argument can come together. Does it need to be either-or? Or can we blend market justice and social justice? Can the US take what’s best from both the commercial business world and the public sector world?

My answer is Yes. And we’ll look at a successful plan that did just that 20 years ago.

I’ll see you then.