Last Tuesday, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the first 10 medicines that will be subject to price negotiations with Medicare starting in 2026 per authorization in the Inflation Reduction Act (2022). It’s a big deal but far from a done deal.

Here are the 10:

- Eliquis, for preventing strokes and blood clots, from Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer

- Jardiance, for Type 2 diabetes and heart failure, from Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly

- Xarelto, for preventing strokes and blood clots, from Johnson & Johnson

- Januvia, for Type 2 diabetes, from Merck

- Farxiga, for chronic kidney disease, from AstraZeneca

- Entresto, for heart failure, from Novartis

- Enbrel, for arthritis and other autoimmune conditions, from Amgen

- Imbruvica, for blood cancers, from AbbVie and Johnson & Johnson

- Stelara, for Crohn’s disease, from Johnson & Johnson

- Fiasp and NovoLog insulin products, for diabetes, from Novo Nordisk

Notably, they include products from 10 of the biggest drug manufacturers that operate in the U.S. including 4 headquartered here (Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Lilly, Amgen) and the list covers a wide range of medical conditions that benefit from daily medications.

But only one cancer medicine was included (Johnson & Johnson and AbbVie’s Imbruvica for lymphoma) leaving cancer drugs alongside therapeutics for weight loss, Crohn’s and others to prepare for listing in 2027 or later.

And CMS included long-acting insulins in the inaugural list naming six products manufactured by the Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk while leaving the competing products made by J&J and others off. So, there were surprises.

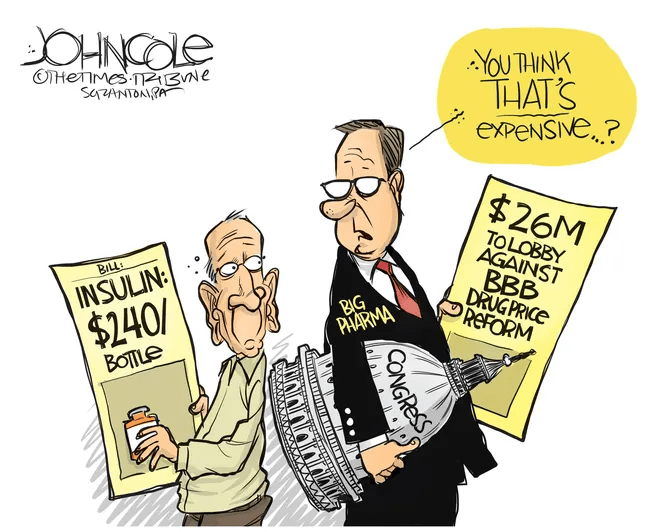

To date, 8 lawsuits have been filed against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by drug manufacturers and the likelihood litigation will end up in the Supreme Court is high.

These cases are being brought because drug manufacturers believe government-imposed price controls are illegal. The arguments will be closely watched because they hit at a more fundamental question:

what’s the role of the federal government in making healthcare in the U.S. more affordable to more people?

Every major sector in healthcare– hospitals, health insurers, medical device manufacturers, physician organizations, information technology companies, consultancies, advisors et al may be impacted as the $4.6 trillion industry is scrutinized more closely . All depend on its regulatory complexity to keep prices high, outsiders out and growth predictable. The pharmaceutical industry just happens to be its most visible.

The Pharmaceutical Industry

The facts are these:

- 66% of American’s take one or more prescriptions: There were 4.73 billion prescriptions dispensed in the U.S. in 2022

- Americans spent $633.5 billion on their medicines in 2022 and will spend $605-$635 billion in 2025.

- This year (2023), the U.S. pharmaceutical market will account for 43.7% of the global pharmaceutical market and more than 70% of the industry’s profits.

- 41% of Americans say they have a fair amount or a great deal of trust in pharmaceutical companies to look out for their best interests and 83% favor allowing Medicare to negotiate pricing directly with drug manufacturers (the same as Veteran’s Health does).

- There were 1,106 COVID-19 vaccines and drugs in development as of March 18, 2023.

- The U.S. industry employs 811,000 directly and 3.2 million indirectly including the 325,000 pharmacists who earn an average of $129,000/year and 447,000 pharm techs who earn $38,000.

- And, in the U.S., drug companies spent $100 billion last year for R&D.

It’s a big, high-profile industry that claims 7 of the Top 10 highest paid CEOs in healthcare in its ranks, a persistent presence in social media and paid advertising for its brands and inexplicably strong influence in politics and physician treatment decisions.

The industry is not well liked by consumers, regulators and trading partners but uses every legal lever including patents, couponing, PBM distortion, pay-to-delay tactics, biosimilar roadblocks et al to protect its shareholders’ interests. And it has been effective for its members and advisors.

My take:

It’s easy to pile-on to criticism of the industry’s opaque pricing, lack of operational transparency, inadequate capture of drug efficacy and effectiveness data and impotent punishment against its bad actors and their enablers.

It’s clear U.S. pharma consumers fund the majority of the global industry’s profits while the rest of the world benefits.

And it’s obvious U.S. consumers think it appropriate for the federal government to step in. The tricky part is not just government-imposed price controls for a handful of drugs; it’s how far the federal government should play in other sectors prone to neglect of affordability and equitable access.

There will be lessons learned as this Inflation Reduction Act program is enacted alongside others in the bill– insulin price caps at $35/month per covered prescription, access to adult vaccines without cost-sharing, a yearly cap ($2,000 in 2025) on out-of-pocket prescription drug costs in Medicare and expansion of the low-income subsidy program under Medicare Part D to 150% of the federal poverty level starting in 2024. And since implementation of these price caps isn’t until 2026, plenty of time for all parties to negotiate, spin and adapt.

But the bigger impact of this program will be in other sectors where pricing is opaque, the public’s suspicious and valid and reliable data is readily available to challenge widely-accepted but flawed assertions about quality, value, access and outcomes. It’s highly likely hospitals will be next.

Stay tuned.