It’s open enrollment season again. From now through Dec. 7, about 65 million Americans are facing the annual question of which Medicare options will give them the best health coverage. An onslaught of television and radio ads, emailed promotions, texts and mailers serve as reminders, though not necessarily clarifying ones.

“It’s a very consequential decision, and the most important thing is to be informed,” said Jeannie Fuglesten Biniek, a senior policy analyst at the Kaiser Family Foundation and a co-author of a recent literature review comparing Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.

If you are navigating this decision for yourself or for a loved one, here are some of the important factors to consider.

Why the marketing barrage?

Medicare — the federally funded health care program — has been in place since 1965. Since then, an expanding array of Medicare Advantage plans have become available. For 2023, the typical beneficiary can choose from 43 Advantage plans, the Kaiser Family Foundation has reported.

Medicare Advantage plans, like traditional Medicare, are funded by the federal government, but they are offered though private insurance companies, which receive a set payment for each enrollee. The idea is to help control costs by allowing these insurers, who must cover the same services as traditional Medicare, to keep some of the federal payment as profit if they can provide care less expensively.

The biggest providers of Advantage plans are Humana and United Healthcare, and they and others market aggressively to persuade seniors to sign up or switch plans. A new U.S. Senate report found that some of these Advantage plan practices are deceptive; for example, some marketing firms sent Medicare beneficiaries mailers made to look like government websites or letters. This has confused many seniors, and Medicare officials have promised to increased policing.

But the marketing has paid off for insurers. The proportion of eligible Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans has hit 48 percent. By next year, most beneficiaries will likely be Advantage enrollees.

Which is better: Medicare or Medicare Advantage?

The two plans operate quite differently, and the health and financial consequences can be dramatic. Each has, well, advantages — and disadvantages.

Jeannie Fuglesten Biniek, a senior policy analyst at the Kaiser Family Foundation, is a co-author of a recent literature review comparing Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. One important finding, Dr. Biniek said: “Both Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported that they were satisfied with their care — a large majority in both groups.”

Advantage plans offer simplicity. “It’s one-stop shopping,” she added. “You get your drug plan included, and you don’t need a separate supplemental policy,” the kind that traditional Medicare beneficiaries often buy, frequently called Medigap policies.

Medicare Advantage may appear cheaper, because many plans charge low or no monthly premiums. Unlike traditional Medicare, Advantage plans also cap out-of-pocket expenses. Next year, you’ll pay no more than $8,300 in in-network expenses, excluding drugs — or $12,450 with the kind of plan that permits you to also use out-of-network providers at higher costs.

Only about one-third of Advantage plans (called P.P.O.s, or preferred provider organizations) allow that choice, however. “Most plans operate like an H.M.O. — you can only go to contracted providers,” said David Lipschutz, the associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy.

Advantage enrollees may also be drawn to the plan by benefits that traditional Medicare can’t offer. “Vision, dental and hearing are the most popular,” Mr. Lipschutz said, but plans may also include gym memberships or transportation.

“We caution people to look at what the scope of the benefits actually are,” he added. “They can be limited, or not available, to everyone in the plan. Dental care might cover one cleaning and that’s it, or it may be broader.” Most Advantage enrollees who use these benefits still wind up paying most dental, vision or hearing costs out of pocket.

What are the downsides to Medicare Advantage?

One big downside is that these insurers require “prior authorization,” or approval in advance, for many procedures, drugs or facilities.

“Your doctor or the facility says that you need more care” — in a hospital or nursing home, say — “but the plan says, ‘No, five days, or a week, two weeks, is fine,’” said David Lipschutz, the associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy. Then you must either forgo care or pay out of pocket.

Advantage participants who are denied care can appeal, and those who do so see the denials reversed 75 percent of the time, according to a 2018 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’s Office of Inspector General. But only about 1 percent of beneficiaries or providers file appeals, “which means there’s a lot of necessary care that enrollees are going without,” Mr. Lipschutz said.

Another report this spring by the inspector general’s office determined that 13 percent of services denied by Advantage plans met Medicare coverage rules and would have been approved under traditional Medicare.

Advantage plans can also be problematic if you are traveling or spending part of each year away from home. If you live in Philadelphia but get sick on vacation in Florida, all local providers may be out of network. Check to see how the plan you’re using or considering treats such situations.

So maybe I should just go with traditional Medicare?

“The big pro is that there are no networks,” Jeannie Fuglesten Biniek, a senior policy analyst at the Kaiser Family Foundation, said of traditional Medicare. “You can see any doctor that accepts Medicare,” as most do, and use any hospital or clinic. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries also largely avoid the delays and frustrations of prior authorization.

But traditional Medicare sets no cap on out-of-pocket expenses, and its 20 percent co-pay can add up quickly for hospitalizations or expensive tests and procedures. So most beneficiaries rely on supplemental insurance to cover those costs; either they buy a Medigap policy or they have supplementary coverage through an employer or Medicaid. Medigap policies are not inexpensive; a Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that they average $150 to $200 a month.

The Kaiser literature review found that traditional Medicare beneficiaries experienced fewer cost problems than Advantage beneficiaries if they had supplementary Medigap policies — but if they didn’t, they were more likely to report problems like delaying care for cost reasons or having trouble paying medical bills.

Traditional Medicare also provides somewhat better access to high-quality hospitals and nursing homes. David Meyers, a health services researcher at Brown University, and his colleagues have been tracking differences between original Medicare and Medicare Advantage for years, using data from millions of people.

The team has found that Advantage beneficiaries are 10 percent less likely to use the highest quality hospitals, four to eight percent less likely to be admitted to the highest quality nursing homes and half as likely to use the highest-rated cancer centers for complex cancer surgeries, compared to similar patients in the same counties or ZIP codes.

In general, patients with high needs — people who were frail, limited in activities of daily living or had chronic conditions — were more apt to switch to traditional Medicare than those who were not high-need.

“When you’re healthier, you may run into fewer of the limitations of networks and prior authorization,” Dr. Meyers said. “When you have more complex needs, you come up against those more frequently.”

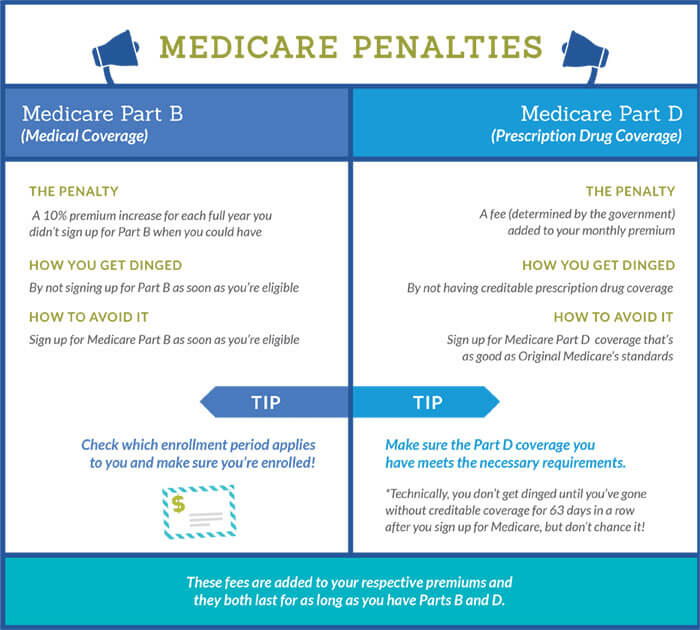

Another downside to traditional Medicare, though, is that it does not include drug coverage. For that, you need to buy a separate Part D plan.

What should I know about drug plans?

Unlike most Medicare Advantage plans, traditional Medicare does not include drug coverage. For that, you must buy a separate Part D plan.

For 2023, beneficiaries can typically choose between 24 stand-alone Part D plans, at premiums that range from $6 to $111 a month and average $43 for policies available nationwide, said Juliette Cubanski, the deputy director of the program on Medicare policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“If you’re the person who doesn’t take many medications or only uses generics, the best strategy might be to sign up for the plan with the lowest premium,” Dr. Cubanski said. “But if you take a lot of medications, the most important thing is whether the drugs you take, especially the most expensive ones, are covered by the plan.”

Different plans cover different drugs (which can change from year to year) and place them in different pricing tiers, so how much you pay for them varies. And, to make comparisons more dizzying, certain pharmacy chains are “preferred” by certain plans, so you could pay more at CVS than at Walmart for the same drug, or vice versa.

How does Part D work? First, most stand-alone plans have a deductible: $505 in 2023. You pay that amount out of pocket before coverage kicks in.

Then, a Part D plan, either stand-alone or as part of a Medicare Advantage plan, usually establishes five tiers for drugs. The cheapest two tiers, for generic drugs, could be free or run up to about $20 per prescription. Next comes a tier for preferred brand-name drugs, probably $30 to $45 per prescription in 2023.

Drugs on the next highest tier, for nonpreferred brand-name drugs, usually involve coinsurance — paying a percentage of the drug’s list price — rather than a flat co-pay. For national stand-alone plans, that ranges from 34 to 50 percent, Dr. Cubanski said.

Drugs that cost more than $830 a month are considered specialty drugs, the highest-priced tier. You only pay 25 percent of the price, but because these are so expensive, your costs rise.

Once your total drug costs reach $4,660 (for 2023), including out of pocket costs and what your plan paid, you have entered the so-called coverage gap phase and will pay 25 percent of the cost, regardless of tier.

Finally, when your costs reach $7,400 — including what you’ve paid, plus the value of manufacturer discounts — you have hit the threshold for catastrophic coverage. After that, you pay just 5 percent.

After I pick a plan, can I switch if I don’t like it?

You can, but be careful.

Switching between Medicare Advantage plans is fairly easy. But switching from traditional Medicare to an Advantage plan can cause a major problem: You relinquish your Medigap policy, if you had one. Then, if you later grow dissatisfied and want to switch back from Advantage to traditional Medicare, you may not be able to replace that policy. Medigap insurers can deny your application or charge high prices based on factors like pre-existing conditions.

(There are some exceptions. For instance, people who drop a Medigap policy to enroll in an Advantage plan for the first time can repurchase it, or buy another Medigap policy, if they switch back to traditional Medicare within a year.)

“Many people think they can try out Medicare Advantage for a while, but it’s not a two-way street,” said David Lipschutz, the associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy. Except in four states that guarantee Medigap coverage at set prices — New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Maine — “it’s one type of insurance that can discriminate against you based on your health,” he said.

The fact is, few consumers do any real comparison shopping, or shift their coverage in either direction. Dozens of lawsuits charging Medicare Advantage insurers with fraudulently inflating their profits apparently haven’t made much difference to consumers, either.

In 2020, only 3 in 10 Medicare beneficiaries compared their current plans with others, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey reported. Even fewer beneficiaries changed plans, which might reflect consumer satisfaction — or the daunting task of trying to evaluate the pluses and minuses.

Where can I find help with these decisions?

You will find plenty of information on the Medicare.gov website, including the Part D plan finder, where you can input the drugs you take and see which plan gives you the best and most economical coverage. The toll-free 1-800-MEDICARE number can also assist you.

Perhaps the best resources, however, are the federally funded State Health Insurance Assistance Programs, where trained volunteers can help consumers assess both Medicare and drug plans.

These programs “are unbiased and don’t have a pecuniary interest in your decision making,” said David Lipschutz, the associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy. But their appointments tend to fill up quickly at this time of year, and the annual open enrollment period ends on Dec. 7. Don’t delay.