Bruising labor battles put Kaiser Permanente’s reputation on the line

The ongoing labor battles have undermined the health giant’s once-golden reputation as a model of cost-effective care that caters to satisfied patients — which it calls “members” — and is exposing it to new scrutiny from politicians and health policy analysts.

Kaiser Permanente, which just narrowly averted one massive strike, is facing another one Monday.

The ongoing labor battles have undermined the health giant’s once-golden reputation as a model of cost-effective care that caters to satisfied patients — which it calls “members” — and is exposing it to new scrutiny from politicians and health policy analysts.

As the labor disputes have played out loudly, ricocheting off the bargaining table and into the public realm, some critics believe that the nonprofit health system is becoming more like its for-profit counterparts and is no longer living up to its foundational ideals.

Compensation for CEO Bernard Tyson topped $16 million in 2017, making him the highest-paid nonprofit health system executive in the nation. The organization also is building a $900 million flagship headquarters in Oakland. And it bid up to $295 million to become the Golden State Warriors’ official health care provider, the San Francisco Chronicle reported. The deal gave the health system naming rights for the shopping and restaurant complex surrounding the team’s new arena in San Francisco, which it has dubbed “Thrive City.”

The organization reported $2.5 billion in net income in 2018 and its health plan sits on about $37.6 billion in reserves.

Against that backdrop of wealth, more than 80,000 employees were poised to strike last month over salaries, retirement benefits and concerns over outsourcing and subcontracting. Nearly 4,000 members of its mental health staff in California are threatening to walk out Monday over the long wait times their patients face for appointments.

“Kaiser’s primary mission, based on their nonprofit status, is to serve a charitable mission,” said Ge Bai, associate professor of accounting and health policy at Johns Hopkins University. “The question is, do they need such an excessive, fancy flagship space? Or should they save money to help the poor and increase employee salaries?”

Lawmakers in California, Kaiser Permanente’s home state, recently targeted it with a new financial transparency law aimed at determining why its premiums continue to increase.

There’s a growing suspicion “that these nonprofit hospitals are not here purely for charitable missions, but instead are working to expand market share,” Bai said.

The scrutiny marks a disorienting role-reversal for Kaiser, an integrated system that acts as both health insurer and medical provider, serving 12.3 million patients and operating 39 hospitals across eight states and the District of Columbia. The bulk of its presence is in California. (Kaiser Health News, which produces California Healthline, is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

Many health systems have tried to imitate its model for delivering affordable health care, which features teams of salaried doctors and health professionals who work together closely, and charges few if any extraneous patient fees. It emphasizes caring and community with slogans like “Health isn’t an industry. It’s a cause,” and “We’re all in this together. And together, we thrive.”

Praised by President Barack Obama for its efficiency and high-quality care, the health maintenance organization has tried to set itself apart from its profit-hungry, fee-for-service counterparts.

Now, its current practices — financial and medical — are getting a more critical look.

As a nonprofit, Kaiser doesn’t have to pay local property and sales taxes, state income taxes and federal corporate taxes, in exchange for providing “charity care and community benefits” — although the federal government doesn’t specify how much.

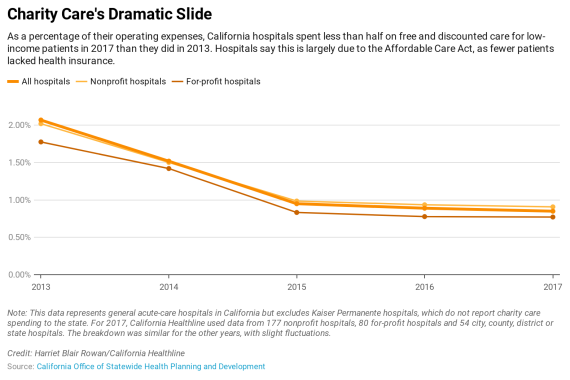

As a percentage of its total spending, Kaiser Permanente’s charity care spending has decreased from 1.29% in 2012 to 0.8% in 2017. Other hospitals in California have exhibited a similar decrease, saying there are fewer uninsured patients who need help since the Affordable Care Act expanded insurance coverage.

CEO Tyson told California Healthline that he limits operating income to about 2% of revenue, which pays for things like capital improvements, community benefit programs and “the running of the company.”

“The idea we’re trying to maximize profit is a false premise,” he said.

The organization is different from many other health systems because of its integrated model, so comparisons are not perfect, but its operating margins were smaller and more stable than other large nonprofit hospital groups in California. AdventHealth’s operating margin was 7.15% in 2018, while Dignity Health had losses in 2016 and 2017.

Tyson said that executive compensation is a “hotspot” for any company in a labor dispute. “In no way would I try to justify it or argue against it,” he said of his salary. In addition to his generous compensation, the health plan paid 35 other executives more than $1 million each in 2017, according to its tax filings.

Even its board members are well-compensated. In 2017, 13 directors each received between $129,000 and $273,000 for what its tax filings say is five to 10 hours of work a week.

And that $37.6 billion in reserves? It’s about 17 times more than the health plan is required by the state to maintain, according to the California Department of Managed Health Care.

Kaiser Permanente said it doesn’t consider its reserves excessive because state regulations don’t account for its integrated model. These reserves represent the value of its hospitals and hundreds of medical offices in California, plus the information technology they rely on, it said.

Kaiser Permanente said its new headquarters will save at least $60 million a year in operating costs because it will bring all of its Oakland staffers under one roof. It justified the partnership with the Warriors by noting it spans 20 years and includes a community gathering space that will provide health services for both members and the public.

Kaiser has a right to defend its spending, but “it’s hard to imagine a nearly $300 million sponsorship being justifiable,” said Michael Rozier, an assistant professor at St. Louis University who studies nonprofit hospitals.

The Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West was about to strike in October before reaching an agreement with Kaiser Permanente.

Democratic presidential candidates Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg, as well as 132 elected California officials, supported the cause.

California legislators this year adopted a bill sponsored by SEIU California that will require the health system to report its financial data to the state by facility, as opposed to reporting aggregated data from its Northern and Southern California regions, as it currently does. This data must include expenses, revenues by payer and the reasons for premium increases.

Other hospitals already report financial data this way, but the California legislature granted Kaiser Permanente an exemption when reporting began in the 1970s because it is an integrated system. This created a financial “black hole” said state Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), the bill’s author.

“They’re the biggest game in town,” said Anthony Wright, executive director of the consumer group Health Access California. “With great power comes great responsibility and a need for transparency.”

Patient care, too, is under scrutiny.

California’s Department of Managed Health Care fined the organization $4 million over mental health wait times in 2013, and in 2017 hammered out an agreement with it to hire an outside consultant to help improve access to care. The department said Kaiser Permanente has so far met all the requirements of the settlement.

But according to the National Union of Healthcare Workers, which is planning Monday’s walkout, wait times have just gotten worse.

Tyson said mental health care delivery is a national issue — “not unique to Kaiser Permanente.” He said the system is actively hiring more staff, contracting with outside providers and looking into using technology to broaden access to treatment.

At a mid-October union rally in Oakland, therapists said the health system’s billions in profits should allow it to hire more than one mental health clinician for every 3,000 members, which the union says is the current ratio.

Ann Rivello, 50, who has worked periodically at Kaiser Permanente Redwood City Medical Center since 2000, said therapists are so busy they struggle to take bathroom breaks and patients wait about two months between appointments for individual therapy.

“Just take $100 million that they’re putting into the new ‘Thrive City’ over there with the Warriors,” she said. “Why can’t they just give it to mental health?”