This is National Hospital week. It comes at a critical time for hospitals:

The U.S. economy is strong but growing numbers in the population face financial insecurity and economic despair. Increased out-of-pocket costs for food, fuel and housing (especially rent) have squeezed household budgets and contributed to increased medical debt—a problem in 41% of U.S. households today. Hospital bills are a factor.

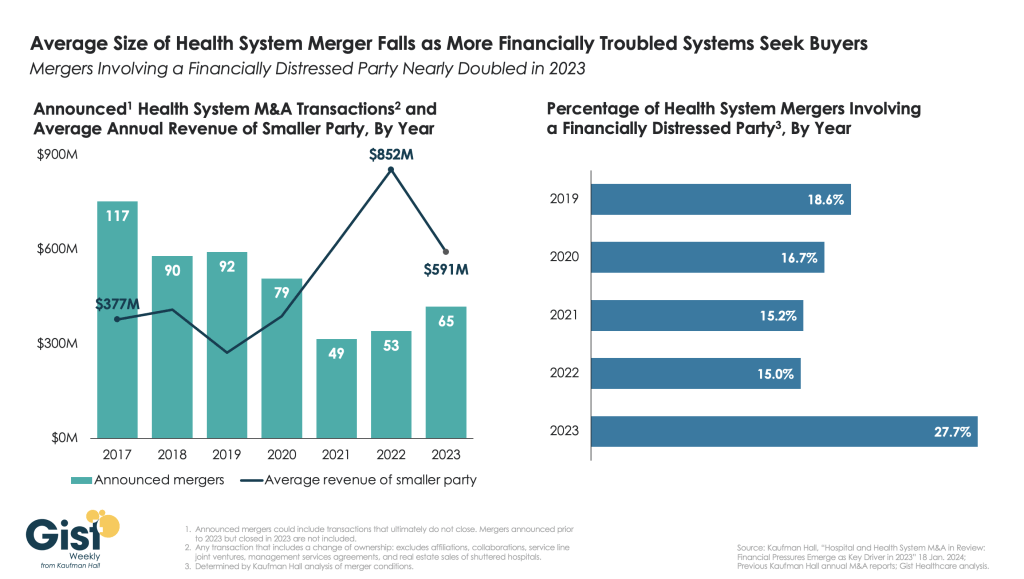

The capital market for hospitals is tightening: interest rates for debt are increasing, private investments in healthcare services have slowed and valuations for key sectors—hospitals, home care, physician practices, et al—have dropped. It’s a buyer’s market for investors who hold record assets under management (AUM) but concerns about the harsh regulatory and competitive environment facing hospitals persist. Betting capital on hospitals is a tough call when other sectors appear less risky.

Utilization levels for hospital services have recovered from pandemic disruption and operating margins are above breakeven for more than half but medical inflation, insurer reimbursement, wage increases and Medicare payment cuts guarantee operating deficits for all. Complicating matters, regulators are keen to limit consolidation and force not-for-profits to justify their tax exemptions. Not a pretty picture.

And, despite all this, the public’s view of hospitals remains positive though tarnished by headlines like these about Steward Health’s bankruptcy filing last Monday:

- Who is Ralph de la Torre? The CEO of Steward Health Care with a $40 million yacht (msn.com)

- The Private-Equity Deal That Flattened a Hospital Chain and Its Landlord – WSJ

- One of the Biggest Hospital Failures in Decades Raises Concerns for Patient Care – WSJ

- Steward Health Care files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy | Healthcare Dive

- Steward plans sale of all hospitals, reports $9B in debt (beckershospitalreview.com)

- What Steward Health Care’s bankruptcy means for patient care | Modern Healthcare

- As Steward Ship Was Sinking, CEO Bought $40M Yacht | MedPage Today

- Steward files for bankruptcy: What physicians need to know (beckersphysicianleadership.com)

- Why is Healey saying everything at Steward hospitals will be OK? (bostonglobe.com)

- Bankrupt Steward Health puts its hospitals up for sale, discloses $9 bln in debt | Reuters

- Steward Health Care bankruptcies: Can they get that process right? (bostonglobe.com)

The public is inclined to hold hospitals in high regard, at least for the time being. When asked how much trust and confidence they have in key institutions to “to develop a plan for the U.S. health system that maximizes what it has done well and corrects its major flaws,” consumers prefer for solutions physicians and hospitals over others but over half still have reservations:

| A Great Deal | Some | Not Much/None | |

| Health Insurers | 18% | 43% | 39% |

| Hospitals | 27% | 52% | 21% |

| Physicians | 32% | 53% | 15% |

| Federal Government | 14% | 42% | 44% |

| Retail Health Org’s | 21% | 51% | 28% |

The American Hospital Association (AHA) is rightfully concerned that hospitals get fair treatment from regulators, adequate reimbursement from Medicare and Medicaid and protection against competitors that cherry-pick profits from the health system.

It can rightfully assert that declining operating margins in hospitals are symptoms of larger problems in the health system: flawed incentives, inadequate funding for preventive and primary care, the growing intensity of chronic diseases, medical inflation for wages, drugs, supplies and technologies, the dominance of ‘Big Insurance’ whose revenues have grown 12.1% annually since the pandemic and more. And it can correctly prove that annual hospital spending has slowed since the pandemic from 6.2% (2019) to 2.2% (2022) in stark contrast to prescription drugs (up from 4% to 8.4% and insurance costs (from -5.4% to +8.5%). Nonetheless, hospital costs, prices and spending are concerns to economists, regulators and elected officials.

National health spending data illustrate the conundrum for hospitals: relative to the overall CPI, healthcare prices and spending—especially outpatient hospital services– are increasing faster than prices and spending in other sectors and it’s getting attention: that’s problematic for hospitals at a time when 5 committees in Congress and 3 Cabinet level departments have their sights set on regulatory changes that are unwelcome to most hospitals.

My take:

The U.S. market for healthcare spending is growing—exceeding 5% per year through the next decade. With annual inflation targeted to 2.0% by the Fed and the GDP expected to grow 3.5-4.0% annually in the same period, something’s gotta’ give. Hospitals represent 30.4% of overall spending today (virtually unchanged for the past 5 years) and above 50% of total spending when their employed physicians and outside activities are included, so it’s obvious they’ll draw attention.

Today, however, most are consumed by near-term concerns– reimbursement issues with insurers, workforce adequacy and discontent, government mandates– and few have the luxury to look 10-20 years ahead.

I believe hospitals should play a vital role in orchestrating the health system’s future and the role they’ll play in it. Some will be specialty hubs. Some will operate without beds. Some will be regional. Some will close. And all will face increased demands from regulators, community leaders and consumers for affordable, convenient and effective whole-person care.

For most hospitals, a decision to invest and behave as if the future is a repeat of the past is a calculated risk. Others with less stake in community health and wellbeing and greater access to capital will seize this opportunity and, in the process, disable hospitals might play in the process.

Near-term reactive navigation vs. long-term proactive orchestration–that’s the crossroad in front of hospitals today. Hopefully, during National Hospital Week, it will get the attention it needs in every hospital board room and C suite.

PS: Last week, I wrote about the inclination of the 18 million college kids to protest against the healthcare status quo (“Is the Health System the Next Target for Campus Unrest?” The Keckley Report May 6, 2024 www.paulkeckley.com). This new survey caught my attention:

According to the Generation Lab’s survey of 1250 college students released last week, healthcare reform is a concern. When asked to choose 3 “issues most important to you” from its list of 13 issues, healthcare reform topped the list. The top 5:

- Health Reform (40%)

- Education Funding and access (38%)

- Economic fairness and opportunity (37%)

- Social justice and civil rights (36%)

- Climate change (35%)

If college kids today are tomorrow’s healthcare workforce and influencers to their peers, addressing the future of health system with their input seems shortsighted. Most hospital boards are comprised of older adults—community leaders, physicians, et al.

And most of the mechanisms hospitals use to assess their long-term sustainability is tethered to assumptions about an aging population and Medicare.

College kids today are sending powerful messages about the society in which they aspire to be a part. They’re tech savvy, independent politically and increasingly spiritual but not religious. And the health system is on their radar.