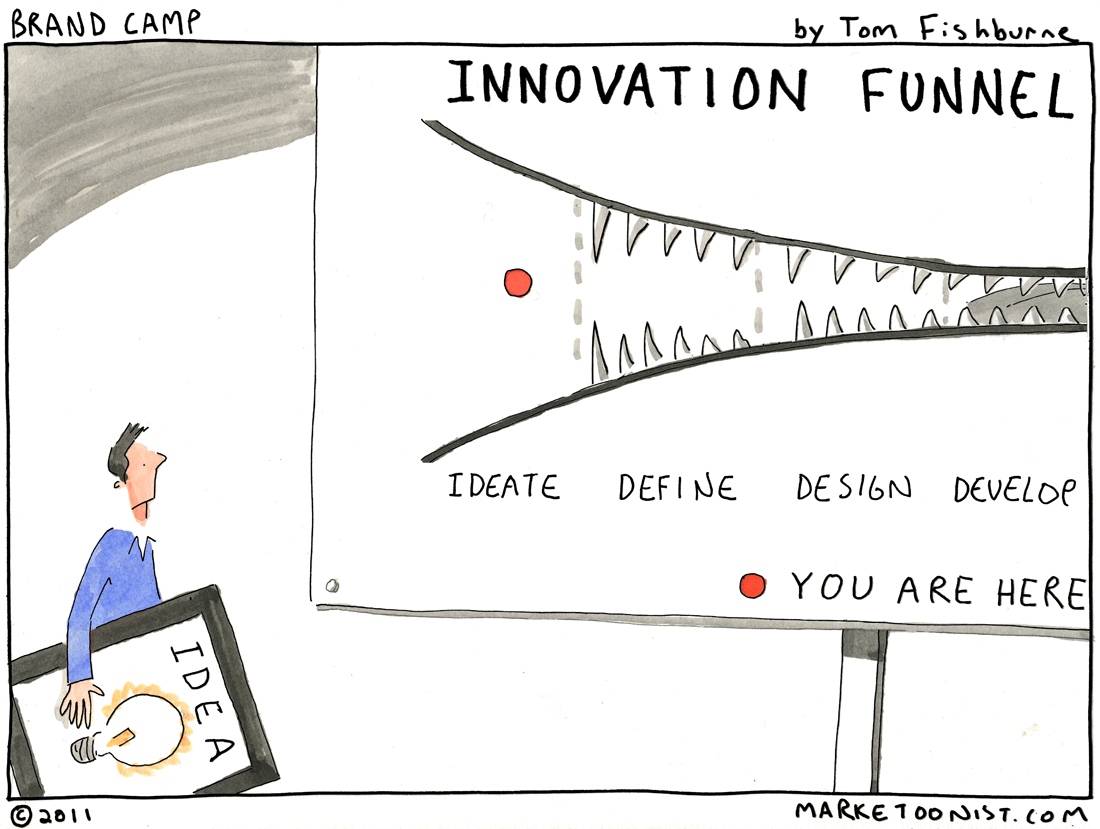

Cartoon – The Innovation Funnel

The Trump administration will release billions in risk-adjustment payments to insurers this fall, ending a relatively short-lived freeze that generated pushback from payers and providers alike.

“This rule will restore operation of the risk-adjustment program and mitigate some of the uncertainty caused by the New Mexico litigation,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement. “Issuers that had expressed concerns about having to withdraw from markets or becoming insolvent should be assured by our actions today. Alleviating concerns in the market helps to protect consumer choices.”

The final rule (PDF), released by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) on Tuesday evening, maintains the same methodology for risk-adjustment transfers previously outlined by the agency, using statewide average premiums as part of the formula. CMS included an additional explanation in the rule on the formula.

For the 2018 and 2019 benefit years, CMS will adjust statewide average premiums by 14% to account for an estimated proportion of administrative costs that do not vary with claims. The agency will not apply an adjustment to the 2017 plan payments “to protect the settled expectations of insurers” that have already calculated pricing and offering decisions based on the 2017 formula.

“Absent this administrative action, HHS would be unable in the coming months to collect charges or make payments to issuers for the 2017 benefit year,” the rule states. “These amounts total billions of dollars, and failure to make the payments in a timely manner threatens to undermine the stability of the insurance markets.”

CMS suspended the $10.4 billion in risk-adjustment payments earlier this month, citing a New Mexico court decision in February that vacated the use of statewide average premiums to calculate risk-adjustment payments. The agency asked the district court judge to reconsider his ruling, but that decision isn’t expected until the end of August.

Most policy experts expected CMS to unfreeze the payments, and late last week the agency sent an interim rule to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review.

Several insurers were quick to denounce the freeze. Physician and hospital groups like the American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association had also urged CMS to reinstate the payments in recent weeks.

The House voted Tuesday to repeal the excise tax on medical devices, with nearly five-dozen Democrats joining all but one Republican in backing the bill.

The measure was approved on a 283-132 vote that comes before lawmakers leave Washington for their summer recess at the end of the week.

The 2.3 percent tax on some devices sold by medical manufacturers was created under the Affordable Care Act. It is not set to take effect until 2020, following a move by lawmakers to include its postponement as part of the deal that ended a government shutdown in January. But lawmakers of both parties have long sought to repeal the tax, arguing that its enactment could lead to higher prices for consumers as well as the loss of tens of thousands of manufacturing jobs.

Fifty-seven Democrats joined 226 Republicans in approving the measure Tuesday night. The path forward in the Senate remains uncertain.

https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/27/insurance-start-up-launches-on-demand-health-coverage.html

Technology has made on-demand services a reality for everything from food deliveries to gym classes and car-sharing. What if you could have on-demand health coverage for big-ticket procedures like knee surgery?

On-demand health insurance seems like an oxymoron, but digital health insurance firm Bind is betting that by structuring health plans so that people can add coverage and pay for it when they need it, companies and employees can save money in the long run.

“It’s not intuitive for people, but I think when we started this we thought, ‘how do people really use the health-care system?’ And we used it in an on-demand way,” explained Tony Miller, co-founder and CEO of Bind.

The two-year old start-up is not a full-fledged insurer, it administers benefits for self-insured employers using UnitedHealth Group’sprovider networks and data analytics. Using its own proprietary algorithms, powered by machine learning, Bind discovered that it could break out certain procedures and reduce health benefit costs more effectively than with a high-deductible plan. It is backed by Ascension Ventures, Lemhi Ventures and UnitedHealthcare.

Plans are designed with basic co-pays and no deductibles for core medical coverage. In addition to free preventive care required under the Affordable Care Act, Bind’s plans cut out deductibles for primary care and specialist visits, maternity coverage, hospital care, medications and even cancer treatment. Co-pays are priced on a sliding scale — from $15 for a visit to retail clinic to $100 at an urgent care facility.

The big-ticket out-of-pocket costs kick in for elective procedures, such as knee replacement or back surgery. The extra co-pay for those procedures is based on the total cost, with consumers being given the full price of the procedure up front and no surprise bills on the back end. The co-pay can be structured so the worker can pay it off through payroll deductions, like a premium.

By outlining the total costs, Bind said it helps employees generate 10 to 15 percent in savings for themselves and for their employer compared to traditional out-of-pocket deductible plans.

“A market might be $6,000 to $24,000 for knee arthroscopy,” explained Miller. “What Bind does is says (for) the $6,000 performer — you only have to pay $1,000 to have access to them. If you want to go to the $24,000 knee arthroscopy with no difference in quality, no difference in performance, you have to pay $6,000 as a consumer.”

“What happens is the consumers actually go and buy the more cost-effective provider and they save money. But more importantly, the entire pool saves money … we save $18,000 for the group,” he said.

That was the way high-deductible plans were supposed to work, with consumers making the most cost-effective choice. Miller should know. He co-founded Definity Health in the late 1990s, which helped pioneer so-called consumer directed health plans; UnitedHealth bought that firm in 2004.

Does he worry that employers could use Bind’s on-demand plans to skimp on core benefits, and shift more costs to their workers? He does.

“What I would worry about is, taking this very novel plan design and if someone wanted to create a skinny plan out of it,” which he admitted would defeat the goal of Bind plan designs.

“Let’s make sure we fund the things we all need in health insurance and make sure that’s a part of everyone’s core benefit,” he said.

Bind has so far signed up small regional employers for its plan, but hopes to launch with a large Fortune 500 company for 2019 coverage.

As high health costs squeeze employers, managed care is making a comeback.

Nineties throwbacks have swept through music, television and fashion. Some startups want to bring a bit of that vintage feel to your workplace health insurance plan.

Health maintenance organizations drove down costs but were painted as villains in that decade for limiting patient choice, rationing care and leaving consumers to grapple with high bills for out-of-network services. But some features of the plans are regaining currency. Companies reviving the model say that new technology and better customer service will help avoid the mistakes of the past.

Rising health-care costs and dissatisfaction with high-deductible plans that ask workers to shoulder more of the burden are pushing employers to consider new ways of controlling spending—and to rethink the trade-offs they’re willing to make to save money.

Medical costs have increased roughly 6 percent a year for the past half-decade, according to PwC’s Health Research Institute, outpacing U.S. economic growth and eroding workers’ wage gains. Some employers, such as Amazon.com Inc., Berkshire Hathaway Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co.—wary of asking workers to pay even more—are trying to rebuild their health programs.

Barry Rose, superintendent of the Cumberland School District in northern Wisconsin, went shopping recently for a new health plan for the district’s 290 employees and family members after its annual coverage costs threatened to top $2 million.

“How do we provide quality, affordable and usable health care for employees,” said Rose. “I can’t keep taking money out of their paychecks to spend on health insurance.”

The company he picked, called Bind, is part of a new generation of health plans putting a tech-savvy spin on cost controls pioneered by HMOs.

Bind, started in 2016, ditches deductibles in favor of fixed copays that consumers can look up on a mobile app or online before heading to the doctor. Another upstart, Centivo, founded in 2017, uses rewards and penalties to nudge workers to get most of their care and referrals for specialists from primary-care doctors.

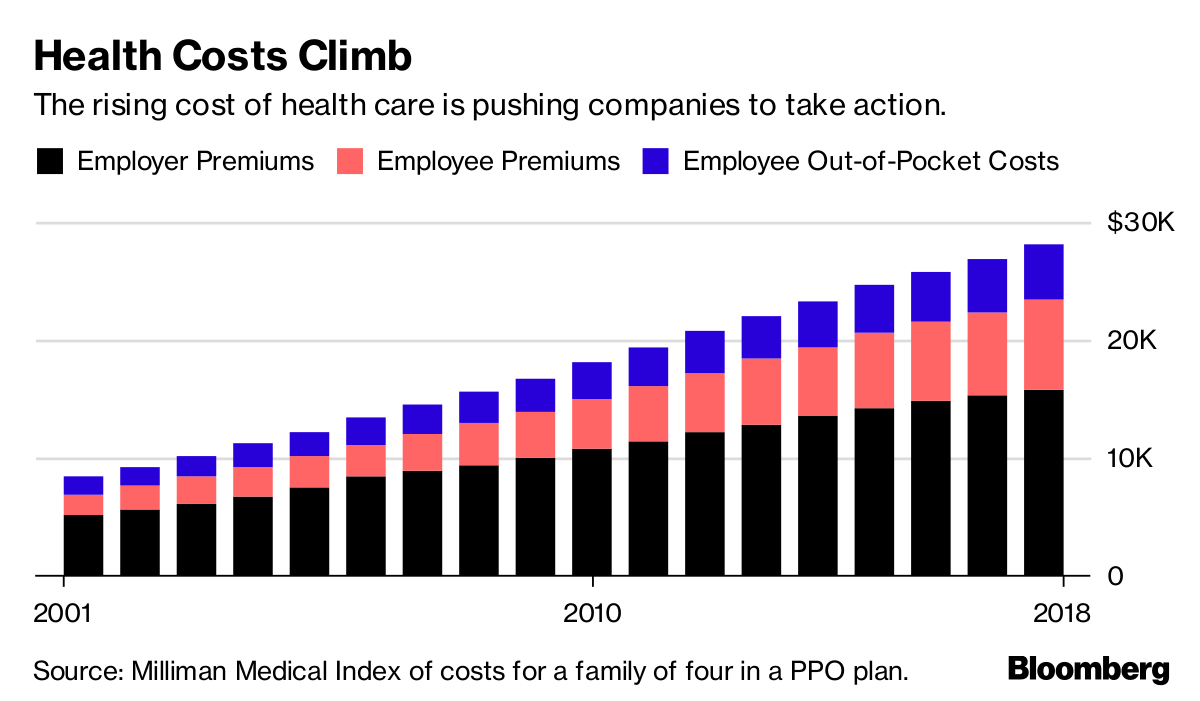

The rising cost of health care is pushing companies to take action.

For many years, employers offered health plans that paid the bills when workers went to see just about any doctor, imposing few limits on care. The companies themselves usually paid much or all of the premiums.

Confronted with rising costs in the 1990s, many employers switched to HMOs or other forms of what became known as managed care. The switch worked, helping hold health costs down for much of the decade.

Soon, however, consumer and physician opposition grew amid horror stories of mothers pushed out of the hospital soon after childbirth, or patients denied cancer treatments. States and the federal government passed laws to protect consumers, and, in 1997, then-President Bill Clinton appointed a panel to create a health consumers’ Bill of Rights.

“The causes of the backlash are much deeper than the specific irritations or grievances we hear about,” Alain Enthoven, the Stanford health economist who helped pioneer the idea of managed care, said in a 1999 lecture. “They are first, that the large insured employed American middle class rejects the very idea of limits on health care because they don’t see themselves as paying for the cost.”

Workers would soon bear the cost, though. By the end of the decade, employers had moved away from these limited health plans. In their wake, costs skyrocketed, giving rise to a new cost-containment tool: high deductibles.

Centivo co-founder Ashok Subramanian spent the past decade trying to figure out how to offer better health insurance at work. His first startup, Liazon, helped workers pick from a big menu of coverage options. He sold it for some $215 million to Towers Watson in 2013, but he said it didn’t fix the bigger problem: Workers had lots of options, but none of them were very good.

“Yes, we were increasing choice, yes we were enabling personalization, but the choices themselves were not that good,” Subramanian said in an interview. “The choices themselves were predicated on a system in which the fundamental incentives in health care are broken.”

Tony Miller, Bind’s founder, helped give rise to health plans with high out-of-pocket costs. He sold a company called Definity Health that combined health plans with savings accounts to UnitedHealth Group Inc. for $300 million in 2004. He now says high-deductible plans failed to deliver on their promises.

“There’s a fever pitch of frustration at employers,” he said. “They’re tired of using the same levers that they’ve been using for the past 20 years.”

UnitedHealth, the biggest U.S. health insurer, helped create Bind with Miller’s venture capital firm and is an investor in the company, which has raised a total of $82 million. Bind is also using UnitedHealth’s network of doctors and hospitals as well as some of its technology.

Centivo has raised $34 million from investors including Bain Capital Ventures.

Centivo and Bind both promise to reduce costs for patients and employers while making it easier to find doctors and check coverage. They say they’ll reduce costs by making sure patients get the care they need, keeping them healthy and avoiding emergencies or unnecessary treatment.

The proportion of Americans under 65 in health plans with high deductibles continues to increase.

In most cases, workers who follow the rules of Centivo’s plans won’t face a deductible. When signing up, employees pick a primary-care doctor, who’s responsible for managing their care and making decisions on whether they need to see a specialist. Care provided or directed by that primary physician is free, as is some treatment for chronic diseases such as diabetes, depending on how employers choose to set up the coverage.

The goal is to ensure workers get the care they need, while avoiding low-value treatments. Those who go to an emergency department in cases that aren’t true emergencies, for example, could face high costs.

“The big question is: Is the market ready for it?” said Mike Turpin, who advises employers on their health benefits as an executive vice president at USI Insurance Services. “The American consumer just has it built into their head that access equals quality.”

Bind bundles its coverage so consumers don’t get billed for lots of charges for services that are part of the same treatment. In Rose’s district, the copay for an emergency room visit is $250, while the cost of a hospital stay is capped at $1,000. Office visits are $35; preventive care is free.

Bind also offers what it calls on-demand insurance. Coverage for planned procedures such as knee surgery, tonsil removal or bariatric surgery must be purchased before the operation. That gives Bind a chance to push customers toward a menu of lower-cost alternatives or cheaper providers.

A patient who looks up knee arthroscopy, for instance, would also be offered physical therapy. The patient’s cost for the surgery ranges from $800 at an outpatient center to more than $6,000, in an example used by Miller. Surgeries in hospitals are typically more costly. Bind also charges more for providers who tend to be less efficient or have worse outcomes.

The ability to view costs upfront is part of what appealed to Rose, the Wisconsin superintendent. “Each of my employees knows exactly what they’re paying for, and they have choice in it,” he said.

Rose said the switch to Bind will save his district several hundred thousand dollars, depending on how much health care his workers need over the next year.

Lawton R. Burns, director of the Wharton Center for Health Management and Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, recently authored a paper with his colleague Mark Pauly arguing that it’s probably impossible to simultaneously improve quality, lower costs and achieve better health outcomes. The ideas now being pushed forward, he writes, are similar to ideas tested in the 1990s.

“It’s deja vu all over again,” he said. “It’s not clear to me, this is just me talking, that people have learned the lessons of the 1990s.”

Toby Cosgrove, MD, the Cleveland Clinic’s former top executive, will share a stage Tuesday afternoon with several colleagues from his new employer: Google.

Cosgrove, who served as the clinic’s CEO from 2004 through 2017, signed on as an executive advisor to the Google Cloud Healthcare and Life Sciences team, the company announced in a blog post last week. An update to his LinkedIn profile indicates he’s been in the role since January.

As part of his new role, Cosgrove will join National Institutes of Health Chief Information Officer Andrea Norris for a conversation Tuesday about how advances in cloud computing are changing healthcare.

Those advances can help stakeholders go beyond achieving the triple-aim of healthcare improvement—better patient experience, improved population health, and reduced cost—to add a fourth aim, according to Gregory J. Moore, MD, PhD, vice president of healthcare for Google Cloud, who will moderate the conversation.

Although advances in technology have added to the recordkeeping burden on healthcare workers, people like Cosgrove can help companies like Google improve the work experience of physicians and their staff, Moore wrote in the blog post.

“Technology may have been the cause of some of these challenges, but we believe that it can also be the cure,” Moore wrote.

Cosgrove, who retired from Cleveland Clinic in January, also joined the board of Denver-based healthcare IT company RxRevu, as HealthLeaders Media reported last month.

Cosgrove’s successor, Tomislav “Tom” Mihaljevic, MD, has been the clinic’s CEO since January.