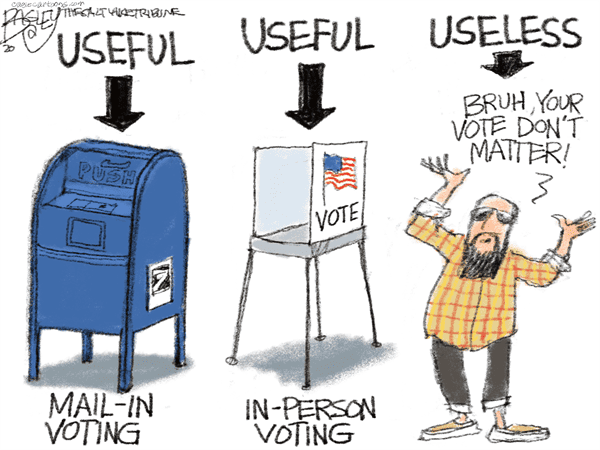

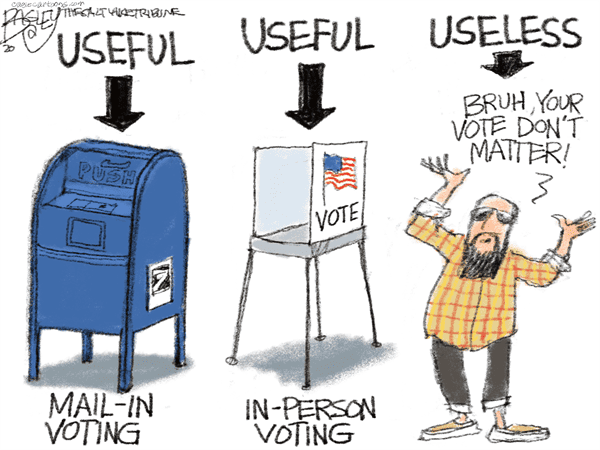

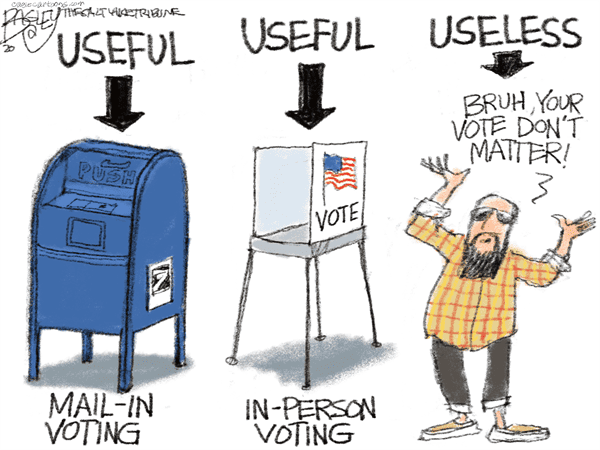

Cartoon – Useful vs. Useless

If you’re looking for the right to vote, you won’t find it in the United States Constitution or the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights recognizes the core rights of citizens in a democracy, including freedom of religion, speech, press and assembly. It then recognizes several insurance policies against an abusive government that would attempt to limit these liberties: weapons; the privacy of houses and personal information; protections against false criminal prosecution or repressive civil trials; and limits on excessive punishments by the government.

But the framers of the Constitution never mentioned a right to vote. They didn’t forget – they intentionally left it out. To put it most simply, the founders didn’t trust ordinary citizens to endorse the rights of others.

They were creating a radical experiment in self-government paired with the protection of individual rights that are often resented by the majority. As a result, they did not lay out an inherent right to vote because they feared rule by the masses would mean the destruction of – not better protection for – all the other rights the Constitution and Bill of Rights uphold. Instead, they highlighted other core rights over the vote, creating a tension that remains today.

James Madison of Virginia. White House Historical Association/Wikimedia Commons

Many of the rights the founders enumerated protect small groups from the power of the majority – for instance, those who would say or publish unpopular statements, or practice unpopular religions, or hold more property than others. James Madison, a principal architect of the U.S. Constitution and the drafter of the Bill of Rights, was an intellectual and landowner who saw the two as strongly linked.

At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Madison expressed the prevailing view that “the freeholders of the country would be the safest depositories of republican liberty,” meaning only people who owned land debt-free, without mortgages, would be able to vote. The Constitution left voting rules to individual states, which had long-standing laws limiting the vote to those freeholders.

In the debates over the ratification of the Constitution, Madison trumpeted a benefit of the new system: the “total exclusion of the people in their collective capacity.” Even as the nation shifted toward broader inclusion in politics, Madison maintained his view that rights were fragile and ordinary people untrustworthy. In his 70s, he opposed the expansion of the franchise to nonlanded citizens when it was considered at Virginia’s Constitutional Convention in 1829, emphasizing that “the great danger is that the majority may not sufficiently respect the rights of the Minority.”

The founders believed that freedoms and rights would require the protection of an educated elite group of citizens, against an intolerant majority. They understood that protected rights and mass voting could be contradictory.

Scholarship in political science backs up many of the founders’ assessments. One of the field’s clear findings is that elites support the protection of minority rights far more than ordinary citizens do. Research has also shown that ordinary Americans are remarkably ignorant of public policies and politicians, lacking even basic political knowledge.

What Americans think of as the right to vote doesn’t reside in the Constitution, but results from broad shifts in American public beliefs during the early 1800s. The new states that entered the union after the original 13 – beginning with Vermont, Kentucky and Tennessee – did not limit voting to property owners. Many of the new state constitutions also explicitly recognized voting rights.

As the nation grew, the idea of universal white male suffrage – championed by the commoner-President Andrew Jackson – became an article of popular faith, if not a constitutional right.

After the Civil War, the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, guaranteed that the right to vote would not be denied on account of race: If some white people could vote, so could similarly qualified nonwhite people. But that still didn’t recognize a right to vote – only the right of equal treatment. Similarly, the 19th Amendment, now 100 years old, banned voting discrimination on the basis of sex, but did not recognize an inherent right to vote.

Andrew Jackson of Tennessee. Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl/Wikimedia Commons

Today, the country remains engaged in a long-running debate about what counts as voter suppression versus what are legitimate limits or regulations on voting – like requiring voters to provide identification, barring felons from voting or removing infrequent voters from the rolls.

These disputes often invoke an incorrect assumption – that voting is a constitutional right protected from the nation’s birth. The national debate over representation and rights is the product of a long-run movement toward mass voting paired with the longstanding fear of its results.

The nation has evolved from being led by an elitist set of beliefs toward a much more universal and inclusive set of assumptions. But the founders’ fears are still coming true: Levels of support for the rights of opposing parties or people of other religions are strikingly weak in the U.S. as well as around the world.

Many Americans support their own rights to free speech but want to suppress the speech of those with whom they disagree.

Americans may have come to believe in a universal vote, but that value does not come from the Constitution, which saw a different path to the protection of rights.

The time is now! Voting in the presidential election will begin in many states in just a few weeks – as early as Sept. 4 in North Carolina. Every state’s regulations and procedures are different, so it is vital that you understand the requirements and opportunities to vote where you live.

Here’s how to make sure you’re ready to vote, and that your vote will count.

Make sure that you are registered to vote at your current address. You may not have voted in a while. You may have moved or changed your name. You may have forgotten when you last registered to vote. Calling or visiting your secretary of state’s office or local Board of Elections may be a good place to start.

You can also visit Vote.org, Rock the Vote, I am a voter or the U.S. Vote Foundation, all nonprofit, nonpartisan websites providing lots of detailed information about voting rights, registration and the process of voting. It took only a few minutes online for me to verify my own registration and voter ID number.

The federal government offers lots of useful voting information, too.

If you’re not registered – whether you have never registered or your registration is out of date – there is still time. September 22 is National Voter Registration Day, when millions of individuals register to vote.

Each state has its own process and deadlines, and you may be able to register online through Vote.org, which can take less than two minutes.

If you’d rather register to vote on paper, download and print a simple form from the federal government, which asks you to provide some personal information, like your name and address. The instructions give state-specific details and provide the mailing address you need to send the form to.

While you’re at it, encourage your friends to register too.

Not everyone who is registered to vote actually casts a ballot. You’re more likely to actually vote if you make a plan.

You’ll need to find out when to vote in person and where to do it. Election Day is Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020 – but different cities and towns have different voting hours. Many communities have several polling places, and you need to go to the right one, depending on where you live. Make sure you know where to go.

In some places you can vote in person for some number of days ahead of Election Day, often at the main municipal government building. Your town office – and its website – will likely have the dates and location information prominently displayed.

If you don’t want to vote in person, either because of your work or personal schedule, or because of the pandemic, think about voting by mail. Some states will mail you a ballot automatically, either because they conduct their elections by mail or because they have made special provisions to do so as a result of the pandemic. In other states you have to request one – and sometimes you need to provide a specific excuse for wanting to avoid in-person voting.

If you’re voting by mail, you may need to pay postage to send your ballot back in. Call your local election office and ask how much you’ll need – and get the right postage. You can order postage online for free delivery – and splitting the cost of a book of stamps is another great opportunity to share voting with a friend.

In 2016, nearly one-quarter of U.S. votes were cast by mail. Research and evidence show that it is safe and reliable – though with large numbers of people expected to vote by mail this year, it’s best to mail your ballot back as early as possible to make sure it has plenty of time to arrive before it needs to be counted. The U.S. Postal Service recommends mailing your ballot at least a week before the deadline.

Large amounts of mail also might mean you don’t get your ballot in the mail until just before the election. If it arrives with less than a week to go, call your local Board of Elections or municipal clerk immediately to find out what your options are. You may be able to drop off the ballot rather than mailing it in, and you should also still have the option to vote in person, either on or before Election Day.

If you’re worried about the safety of voting by mail, there are plenty of administrative and legal protections for mailed-in ballots, and steep penalties for those who tamper with election mail.

Many people set reminders for all sorts of important things: medical appointments, friends’ birthdays, bill payment dates and so on. Add voting to your calendar – including alerts to request a mail-in ballot, to vote early, to mail your ballot and certainly for Election Day itself.

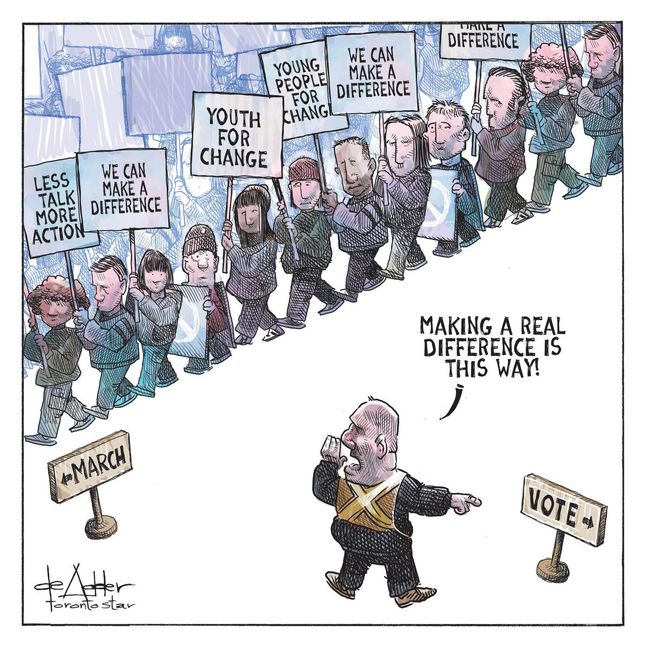

Every vote that is cast is a vital contribution to the nation’s future. Encourage everyone you know to vote. You can even invite people to your calendar events – or share your plans on social media, in an email to family and friends. Send texts to people you know. Pledge to call 10 people and ask them to vote, and ask each of them to call 10 more people.

If you make your plan and follow the requirements of your state and local government, you can cast your ballot and be certain that your vote will count.

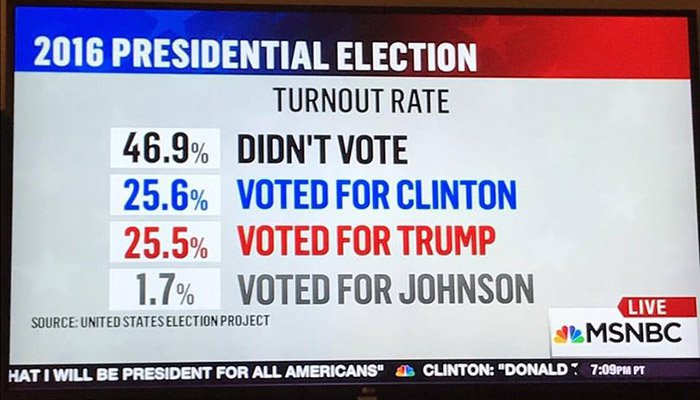

You may encounter people claiming there could be “widespread” voter fraud or that the election is somehow “rigged.” But the biggest problem is that so few people actually vote: In 2016, 40% of eligible American voters didn’t cast a ballot.

It is your right to vote. Exercise that right proudly and make your voice heard.