http://www.commonwealthfund.org/interactives/2017/mar/state-scorecard/

The 2017 edition of the Commonwealth Fund Scorecard on State Health System Performance finds that nearly all state health systems improved on a broad array of health indicators between 2013 and 2015. During this period, which coincides with implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s major coverage expansions, uninsured rates dropped and more people were able to access needed care, particularly those in states that expanded their Medicaid programs. On a less positive note, between 2011–12 and 2013–14, premature death rates rose slightly following a long decline. The Scorecard points to a constant give-and-take in efforts to improve health and health care, reminding us that there is still more to be done.

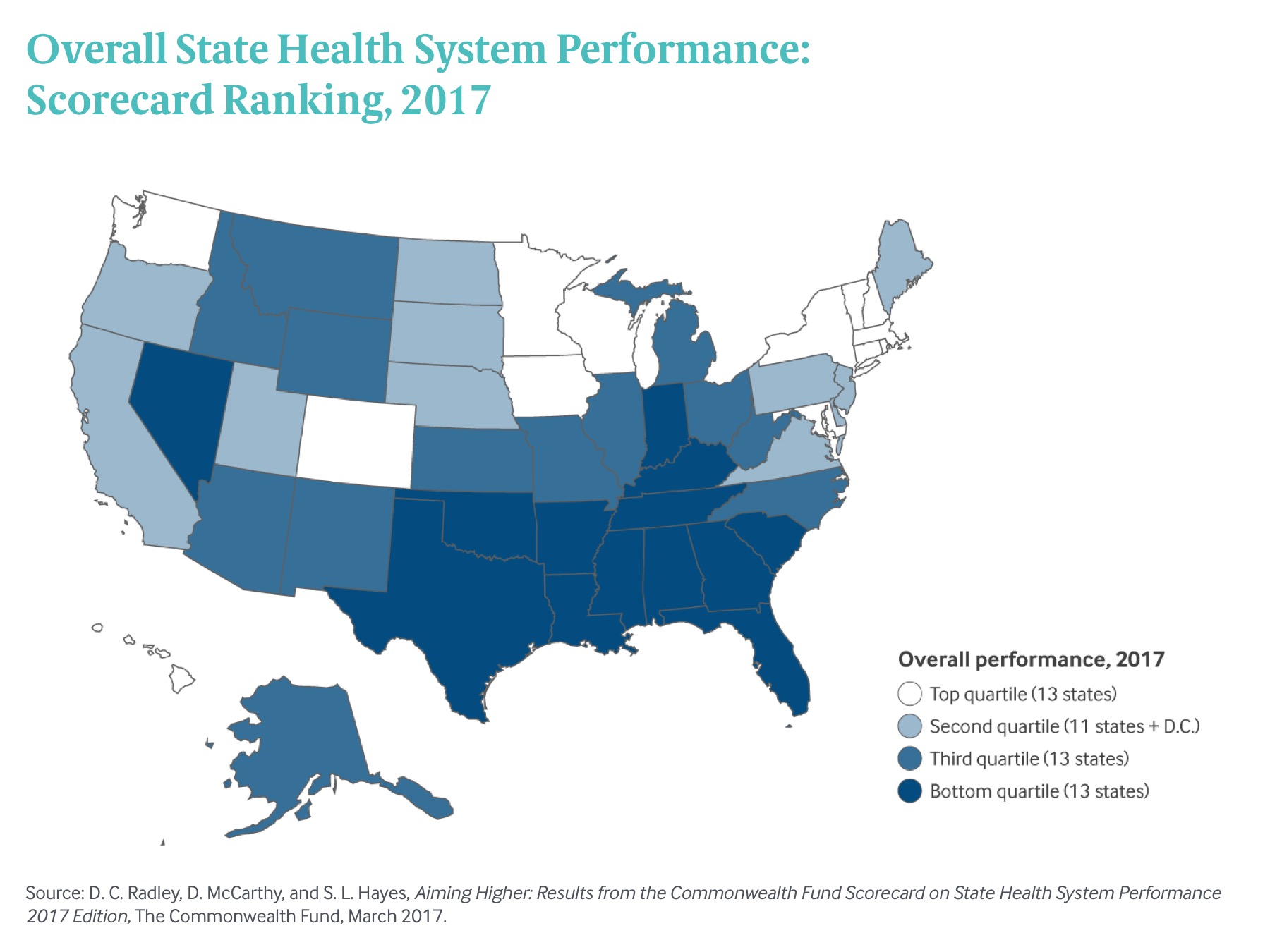

Vermont was the top-ranked state overall in this year’s Scorecard, followed by Minnesota, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts (Exhibit 1). California, Colorado, Kentucky, New York, and Washington made the biggest jumps in ranking, with New York moving into the top-performing group for the first time. Kentucky also stood out for having improved on more measures than any other state.

Exhibit 1: Overall State Health System Performance: Scorecard Ranking, 2017

Exhibit 1: Overall State Health System Performance: Scorecard Ranking, 2017Using the most recent data available, the Scorecard ranks states on more than 40 measures of health system performance in five broad areas: health care access, quality, avoidable hospital use and costs, health outcomes, and health care equity. In reviewing the data, four key themes emerged:

- There was more improvement than decline in states’ health system performance.

- States that expanded Medicaid saw greater gains in access to care.

- Premature death rates crept up in almost two-thirds of states.

- Across all measures, there was a threefold variation in performance, on average, between top- and bottom-performing states, signifying opportunities for improvement.

By 2015, fewer people in every state lacked health insurance. Across the country, more patients benefited from better quality of care in doctors’ offices and hospitals, and Medicare beneficiaries were less frequently readmitted to the hospital. The most pervasive improvements in health system performance occurred where policymakers and health system leaders created programs, incentives, or collaborations to ensure access to care and improve the quality and efficiency of care. For example, the decline in hospital readmissions accelerated after the federal government began levying financial penalties on hospitals that had high rates of readmissions and created hospital improvement innovation networks to help spread best practices. (notes)

Still, wide performance variation across states, as well as persistent disparities by race and economic status within states, are clear signals that our nation is a long way from offering everyone an equal opportunity for a long, healthy, and productive life. Looking forward, it is likely that states will be challenged to provide leadership on health policy as the federal government considers a new relationship with states in public financing of health care. To improve the health of their residents, states must find creative ways of addressing the causes of rising mortality rates while also working to strengthen primary and preventive care.