We learned yesterday that the average cost of a family health insurance policy through an employer reached nearly $27,000 this year, 6% higher than what it cost in 2024. As if that weren’t alarming enough, researchers are predicting that the total likely will soar toward $30,000 next year because of rising medical costs and the unrelenting pressure insurers are under from Wall Street to increase their profits. Small businesses will be hit the hardest.

Despite repeated assurances from insurers that we can count on them to hold down the cost of health care – and consequently the premiums they charge – there are now many years of evidence – from researchers like KFF, which tracks annual changes in employer-sponsored coverage – that they have not and cannot deliver on their promises.

Nevertheless, Big Insurance is doing just fine financially as they force America’s employers and workers to shell out increasingly absurd amounts of money for policies that actually cover less than they did ten years ago. A health insurance policy today is generally less valuable than it was a decade ago because families have to spend more and more money out of their own pockets every year before their coverage kicks in. In addition, they are far more likely to be notified that their insurers will not cover the care their doctors say they need.

When you look at KFF’s reports over time, you’ll see that the cost of a family policy has increased 60% since 2014 when it cost an average of $16,834. That is a rate of increase much higher than general inflation and also higher than medical inflation.

Not only has the total cost of an employer-sponsored plan skyrocketed, so has the share of premiums workers must pay. This year, employers deducted an average of $6,850 from their workers’ paychecks for family coverage, up from $4,823 in 2014, a 42% increase.

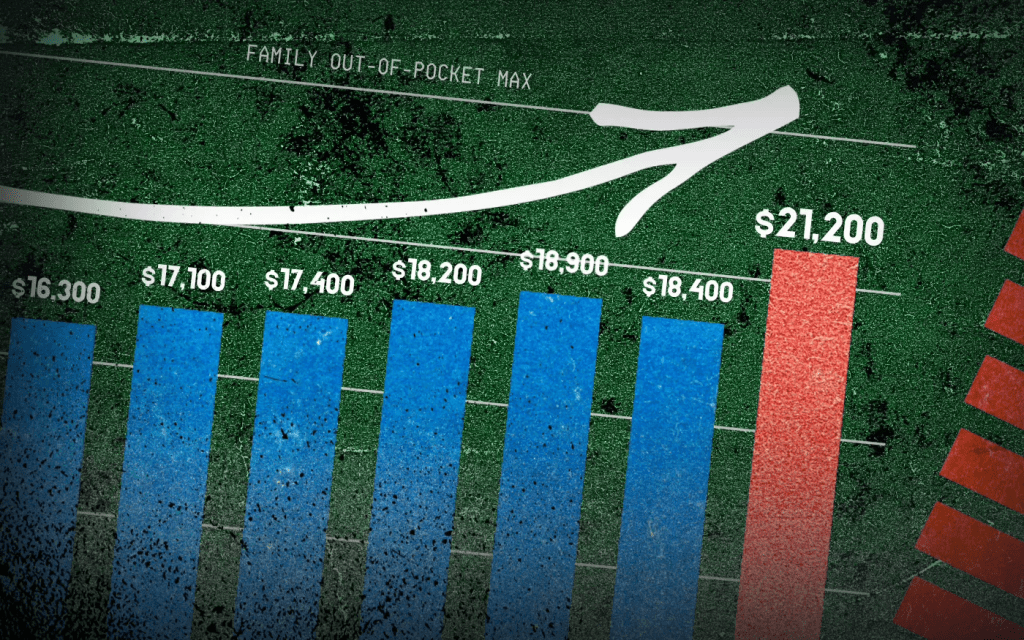

And as premiums have risen, so has the amount of money workers and their dependents are required to spend out of their pockets in deductibles, copayments and coinsurance. The Affordable Care Act, to its credit, instituted a cap on out-of-pocket expenses in 2014, but that cap has been increasing annually along with premiums. (The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services sets the out-of-pocket max every year, pegging it to the average increase in premiums.)

In 2014 the out-of-pocket cap for a family policy was $12,700. Next year, it will rise to $21,200 – a 67% increase. And keep in mind that the cap only applies to in-network care. If you go out of your insurer’s network or take a medication not covered under your policy, you can be on the hook for hundreds or thousands more. While most employer-sponsored plans have caps that are considerably lower, many individuals and families reach the legal max every year.

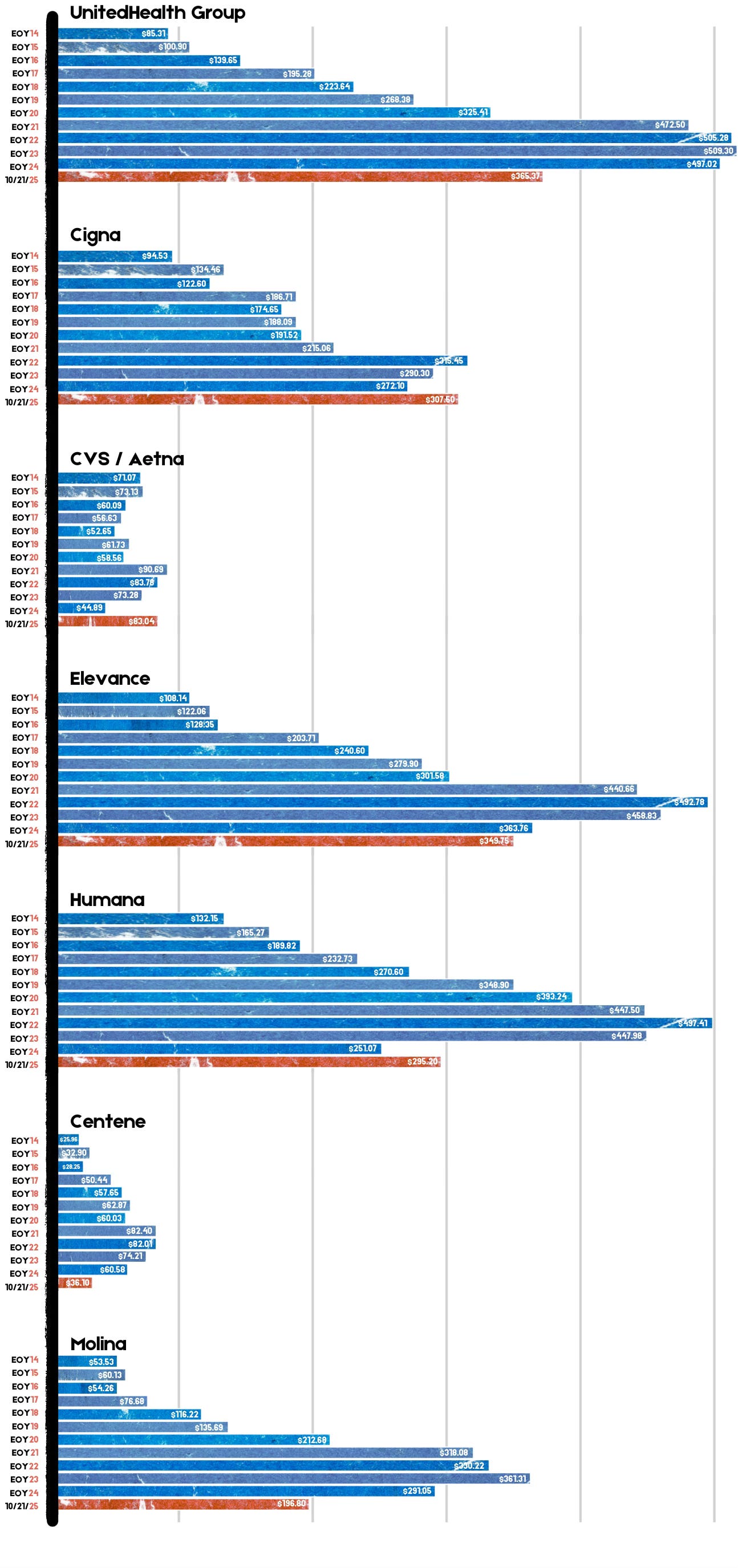

Meanwhile, the seven biggest for-profit health insurers have made hundreds of billions in profits since 2014 as they have jacked up premiums and out-of-pocket requirements and erected numerous barriers, including the aggressive use of prior authorization, that make it more difficult for Americans to get the care and medications they need. Collectively, those seven companies made $71.3 billion in profits last year alone. That was up slightly from $70.7 billion in 2023. Insurers said their 2024 profits were somewhat depressed because more of their health plan enrollees went to the doctor and picked up their prescriptions last year. Investors were furious that insurers couldn’t keep that from happening, as you’ll see in the charts below. Many of them sold some or all of their shares, sending insurers’ stock prices down. But overall, the stock prices of the big insurance conglomerates have increased steadily over the years as we and our employers have had to spend more for policies that cover less.

For example, UnitedHealth Group, the biggest of the seven, saw its stock price increase 483% between 2014 and 2024 – from $85.31 a share on Dec. 31, 2014, to $497.02 on Dec. 31, 2024. Most of the other companies saw similar growth in their shares over that time period.

By contrast, the Dow Jones Industrial Average increased 139% (from $17,823.07 to $42,544.22), and the S&P 500 increased 186% (from $2,058.90 to $5,881.63) during the same period.

Back to those premiums and out-of-pocket requirements. While the KFF numbers pertain to employer-sponsored coverage, people who have to buy health insurance on their own – mostly through the ACA (Obamacare) marketplace – have experienced similar increases. Most Americans who buy their insurance there could not possibly afford it if not for subsidies provided by the federal government on a sliding scale, which is based on income. The most generous subsidies have been available since 2014 to people with income up to 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL). During the pandemic, Congress expanded – or “enhanced” – the subsidies to make them available to people with incomes up to 400% of FPL. Those enhanced subsidies are scheduled to expire at the end of this year. Whether to let them expire or extend them is at the center of the ongoing government shutdown. Most Democrats are insisting they be extended while most Republicans want them to end. It’s important to note that the federal money goes to insurance companies, not to people enrolled in their health plans.

If the enhanced subsidies do end, millions of Americans who get their health insurance through the ACA marketplace will drop their coverage because the premiums will be unaffordable for them and their families. In Pennsylvania where I live, premiums for policies bought on the state’s insurance exchange are expected to increase 102% next year because of the anticipated end of the subsidies and premium inflation.

More than 24 million Americans now get their coverage through the ACA marketplace, primarily because their employers cannot offer health insurance as an employee benefit anymore. Over the past several years, a growing number of small businesses have stopped offering subsidized coverage to their workers because of the expense. Just slightly more than half of U.S. businesses are still in the game. The rest simply can’t afford the premiums. Small businesses can expect an average increase of 11% next year with some of them facing increases of 32%.

It is becoming more clear every passing year that the U.S. has one of the most insidious ways of rationing care. It is rationed based on a person’s ability to pay far more than on a person’s need for care. And among those most disadvantaged by the current system are hard-working low- and middle-income Americans with chronic conditions and those who suddenly get sick or injured.

While the Affordable Care Act prohibited insurers from charging people with pre-existing conditions more than healthier people, insurers have figured out a back door way to discriminate against them: by making them pay hundreds or thousands of dollars out of their own pockets every year – in addition to their premiums – and also by refusing to cover treatments and medications their doctors say they need.

Now you know why Big Insurance is doing so well while the rest of us are getting