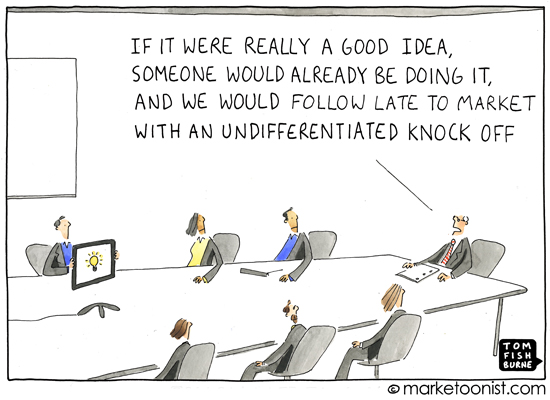

Cartoon – How would you describe my leadership?

Despite the gains in health insurance coverage made under the Affordable Care Act, the United States remains the only high-income nation without universal health coverage. Coverage is universal, according to the World Health Organization, when “all people have access to needed health services (including prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliation) of sufficient quality to be effective while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.”1

Several recent legislative attempts have sought to establish a universal health care system in the U.S. At the federal level, the most prominent of these is Senator Bernie Sanders’ (I–Vt.) Medicare for All proposal (S. 1804, 115th Congress, 2017), which would establish a federal single-payer health insurance program. Along similar lines, various proposals, such as the Medicare-X Choice Act from Senators Michael Bennet (D–Colo.) and Tim Kaine (D–Va.), have called for the expansion of existing public programs as a step toward a universal, public insurance program (S. 1970, 115th Congress, 2017).

At the state level, legislators in many states, including Michigan (House Bill 6285),2 Minnesota (Minnesota Health Plan),3 and New York (Bill A04738A)4 have also advanced legislation to move toward a single-payer health care system. Medicare for All, which enjoys majority support in 42 states, is viewed by many as a litmus test for Democratic presidential hopefuls.5 In recent polling, a majority of Americans supported a Medicare for All plan.6

Medicare for All and similar single-payer plans generally share many common features. They envision a system in which the federal government would raise and allocate most of the funding for health care; the scope of benefits would be quite broad; the role of private insurance would be limited and highly regulated; and cost-sharing would be minimal. Proponents of single-payer health reform often point to the lower costs and broader coverage enjoyed by those covered under universal health care systems around the world as evidence that such systems work.

Other countries’ health insurance systems do share the same broad goals as those of single-payer advocates: to achieve universal coverage while improving the quality of care, improving health equity, and lowering overall health system costs. However, there is considerable variation among universal coverage systems around the world, and most differ in important respects from the systems envisioned by U.S. lawmakers who have introduced federal and state single-payer bills. American advocates for single-payer insurance may benefit from considering the wide range of designs other nations use to achieve universal coverage.

This issue brief uses data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Commonwealth Fund, and other sources to compare key features of universal health care systems in 12 high-income countries: Australia, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, and Taiwan.

We focus on three major areas of variation between these countries that are relevant to U.S. policymakers: the distribution of responsibilities and resources between various levels of government; the breadth of benefits covered and the degree of cost-sharing under public insurance; and the role of private health insurance. There are many other areas of variation among the health care systems of other high-income countries with universal coverage — such as in hospital ownership, new technology adoption, system financing, and global budgeting — that are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Hospitals that serve vulnerable patients have much lower average margins that other providers, according to America’s Essential Hospitals.

The safety-net providers have persistently high levels of uncompensated and charity care that pushed average margins down to one-fifth that of other hospitals in 2017, according to the annual study, Essential Data: Our Hospitals, Our Patients. They operated with an average margin of 1.6 percent in 2017 — less than half their 2016 average and far below the 7.8 percent average of other U.S. hospitals, according to the data from Essential Hospitals’ 300 members.

While these hospitals represent about 5 percent of all U.S. hospitals, they provided 17.4 percent of all uncompensated care, or $6.7 billion, and 23 percent of all charity care, or $5.5 billion in 2017, the study said.

THE IMPACT

Amercia’s Essential Hospitals fears further financial pressure from $4 billion in federal funding cuts to disproportionate share hospitals slated to go into effect on October 1. This represents a third of current funding levels.

The DSH payments are statutorily required and are intended to offset hospitals’ uncompensated care costs. In 2017, Medicaid made a total of $18.1 billion in DSH payments, including $7.7 billion in state funds and $10.4 billion in federal funds, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, or MACPAC.

MACPAC recommends starting with cuts of $2 billion in the first year.

The association and other organizations have been urging Congress to stop or phase-in the cuts. Speaker Nancy Pelosi said Congress must take action to ease the DSH cuts.

TREND

Since 1981, Medicaid DSH payments have helped offset essential hospitals’ uncompensated care costs.

The study data shows essential hospitals provide disproportionately high levels of uncompensated and charity care.

In 2017, three-quarters of essential hospitals’ patients were uninsured or covered by Medicaid or Medicare and 53 percent were racial or ethnic minorities. They served 360,000 homeless individuals, 10 million with limited access to healthy food, 23.9 million living below the poverty line, and 17.1 million without health insurance, the study said.

The association’s members averaged 17,000 inpatient discharges, or 3.1 times the volume of other acute-care hospitals. They operated 31 percent of level I trauma centers and 39 percent of burn care beds nationally.

ON THE RECORD

“Our hospitals do a lot with often limited resources, but this year’s Medicaid DSH cuts will push them to the breaking point if Congress doesn’t step in,” said association President and CEO Dr. Bruce Siegel. “Our hospitals are on the front lines of helping communities and vulnerable people overcome social and economic barriers to good health, and they do much of this work out of their own pocket. They do this because they know going outside their walls means healthier communities and lower costs through avoided admissions and ED visits.”

Here’s this week’s good news in health IT: over 90 percent of hospitals now provide portals or similar platforms allowing patients to electronically access their medical records, according to a new report from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC).

The bad news, however, is that few patients actually use them. Fewer than eight percent of hospitals report that half or more of their patients have activated their patient portal, and nearly 40 percent reported that less than ten percent of patients have logged on. This is in spite of data in the report showing that two-thirds of hospitals offer services like secure messaging, electronic bill pay, and online scheduling that are highly valued by consumers.

The root cause lies in simplicity and connectivity. Each hospital or independent physician practice has its own portal, forcing the patient to manage multiple logins and navigate myriad systems, each of which only displays a slice of their medical records. Rarely can the systems communicate with each other to allow providers access to the patient’s complete record.

Asking patients to navigate multiple portals from different healthcare providers is like asking them to use different web browsers for each site they visit—it’s cumbersome and nonsensical, the hallmark of a design driven by regulatory requirement rather than consumer value.

What’s needed is one, unified consumer portal for healthcare, which integrates all the different providers’ information feeds. For that, we’d need a truly consumer-centric healthcare system, built around and controlled by the individual. Maybe one day.

Healthcare insiders know that clinical quality can be highly variable across providers. But the average patient assumes that the vast majority of providers deliver high-quality clinical care.

The graphic below illustrates the distinction between consumer and physician definitions of “quality”.

Patients’ definition of quality is often closer to what providers consider service quality: was the service available and convenient? Was my appointment on time and efficient? Was the staff courteous and helpful?

As to clinical quality, few patients anticipate a bad outcome, or do extensive research on provider quality unless facing a grave illness. And for those who do, the metrics and methods available to assess quality are hard to interpret, much less to weigh against each other. For example, I know I don’t want a post-op infection, but how much extra am I willing to pay to minimize that risk?

As consumers bear more responsibility for choice of provider—and have a greater range of options to choose from—providers must expand their quality goals beyond clinical quality to encompass service reliability, remembering that the ultimate measure of a good outcome for a patient is whether or not their problem was actually solved.

Frederick Banting discovered insulin in 1921 and didn’t want to profit off of such a life-saving drug. Fast forward to 2019, and the price of insulin continues to increase year over year. Why is that?

To paraphrase Elizabeth Barrett Browning, How do I rig thee? Let me count the ways.

Even research statistics are all too often rigged, according to a commentary in this month’s Journal of the A.M.A. These rigged statistics are being applied to clinical studies of new drugs, devices, and treatments to put them just far enough over the line of “significance” to win Food and Drug Administration approval.

And to win big dollar profits for research companies and the researchers themselves – my claim, not the Journal’s.

This goes beyond what Mark Twain called “lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Twain was referring to “spinning” legitimate statistics to show results in a favorable light.

But Stanford’s John P. A. Ioannidis MD, ScD, calls out statisticians-for-hire for actually cherry-picking, distorting, and manipulating post-hoc the statistical analyses themselves in scientific publications, in the service of Big Pharma.

Ioannidis’s Observations

Here are some of his observations:

Ioannidis’s Solution

Dr. Ioannidis’s offers a solution to keep honest statisticians honest: Require researchers to post in advance, such as at ClinicalTrials.gov, not only the overall research design but also detailed descriptions of

Comment:

Prestigious medical journals could adopt Ioannidis’s solutions without waiting for comprehensive reform of the whole health system. But the Journal’s surfacing of issues around abuse of research statistics illustrates the extent to which that system has fallen under the pall of profits, the depth to which the system has been rigged, and the degree to which Hippocratically-pledged professionals have been coopted. And this means that the full weight of our society, government and nation will be needed to fix it.

Take Action

Now, take action.

The former chief operating officer of Cleveland-based MetroHealth System was sentenced to more than 15 years in prison for his role in a conspiracy to defraud the health system through a series of bribes and kickbacks, according to the Department of Justice.

Five things to know:

1. The sentencing came after former COO Edward Hills, DDS, and three co-defendants — all dentists at MetroHealth — were found guilty of criminal charges in July 2018. The four men were indicted for the crimes in October 2016.

2. According to court documents presented by the Justice Department during the trial, Dr. Hills and two of his co-defendants engaged in a racketeering conspiracy from 2008 through 2016 that involved a series of bribes, witness tampering and other crimes.

3. Federal prosecutors alleged Dr. Hills solicited cash, checks and expensive gifts from the two co-defendants beginning in 2009, and in return took actions on their behalf allowing them to operate their individual private dental clinics during regular business hours while receiving full-time salaries from MetroHealth.

4. Dr. Hills, who also served as interim president and CEO of MetroHealth from December 2012 through July 2013, allowed the co-defendants to hire MetroHealth dental residents to work at their private clinics during regular business hours and did not require them to pay wages or salaries to residents. He allowed the three individuals and others to solicit bribes from prospective dental school residents, which amounted to at least $75,000 between 2008 and 2014.

5. Dr. Hills’ co-defendants are scheduled to be sentenced later this month.