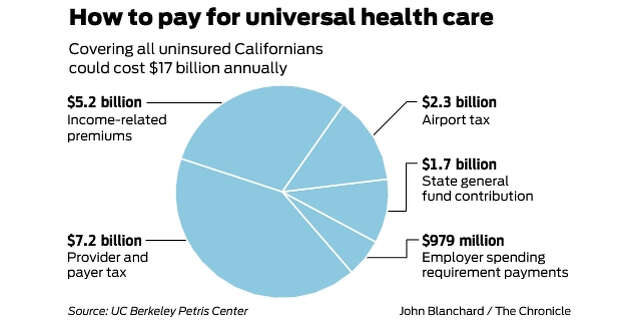

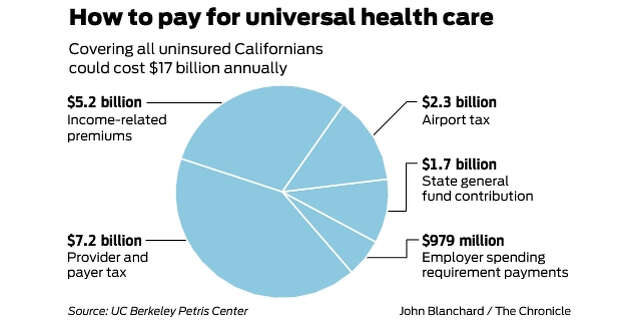

Universal health care in California could cost $17.3 billion a year, under one plan proposed Friday by UC Berkeley health policy researchers.

The paper offers one path for getting about 3 million uninsured Californians health coverage. It is one of several recent estimates from researchers and legislators who have devised various ways to work toward universal coverage in the state. It is not a plan for a single-payer system.

The figure is significantly higher than other analyses, which found that working toward universal coverage by expanding Medi-Cal insurance for the poor would cost less than half of that. That is because the paper builds in the assumption that the uninsured would get on private health insurance plans, whereas other estimates factor in federal funding for getting more people on Medi-Cal, which is jointly paid for by the federal and state governments.

The paper, by Richard Scheffler and Stephen Shortell of Berkeley’s School of Public Health, proposes a mix of new taxes on the health care industry, California employers and airline travelers, paired with contributions from the state’s general fund and premium payments from individuals who are now uninsured.

The ideas, presented Friday to a group of California health policy researchers and advocates, are considered one early stab at financing universal coverage and are not included in legislative proposals.

The largest source of financing, 41 percent, would come from a 3 percent tax on the revenue of hospitals, nursing homes, drug companies, home care providers and insurance companies, which would generate an estimated $7.2 billion a year. The tax would not apply to public hospitals.

The next largest source of funding, 31 percent or $5.2 billion, would come from currently uninsured residents who would pay a monthly premium for a health plan — envisioned as a plan bought through the insurance marketplace Covered California. The premium would be paid by those who earn too much to qualify for Medi-Cal, the insurance program for the poor, and would average out to $123 a month per person. The authors do not specify how many people would pay this premium, or address how to incentivize this population — many of whom are undocumented and hesitant to participate in government programs — to buy into the system.

The paper also proposes a tax on international and business class travelers who fly into and out of California’s five largest airports: Los Angeles International Airport, San Francisco International Airport, San Diego International Airport, Oakland International Airport and San Jose International Airport. The taxes would be $50 per ticket for domestic business class passengers, $60 per ticket for for economy international passengers and $250 per ticket for international business passengers. These five airports see a collective 188 million passengers each year, according to the authors’ analysis of California Department of Transportation air passenger traffic data. The tax would generate $2.3 billion a year.

The remaining funding would come from the state’s general fund in the amount of $1.7 billion, and a tax on employers that would generate $979 million. The employer tax would be modeled after Healthy San Francisco, a program started in 2007 to cover the city’s 14,000 uninsured residents. It would require employers that don’t provide insurance to their workers to pay into a fund by levying a 4 percent surcharge on customers. It would apply to for-profit employers with more than 20 workers and nonprofit employers with more than 50 workers.

Under the plan, the revenue generated through these proposed new taxes would go toward what’s known as integrated care systems to expand their geographic reach and offer more insurance plans on Covered California. The biggest and most well-known integrated system is Kaiser, which provides both the insurance coverage and health care services to its patients, but others have started forming their own integrated care systems in recent years including Sutter Health’s HMO plan, Sharp Health Care in San Diego and HealthCare Partners in Los Angeles. Those integrated care plans would be offered on Covered California.

Scheffler and Shortell say they hope their ideas are a starting point for debate and will inspire action by state legislators.

“We’re hoping for some interest from Sacramento,” Scheffler said.

Some policy experts who reviewed the paper raised questions about some of the proposed taxes and the cost estimate. Ken Jacobs, chair of the UC Berkeley Labor Center, said $17 billion is much too high for achieving universal coverage because it doesn’t take into account the federal dollars that would be available if the state were to expand Medi-Cal to more uninsured people.

A state-level employer mandate could face legal challenges, as Healthy San Francisco did, because of federal preemption issues under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, or ERISA, Jacobs said. Similarly, the airline tax might run afoul of federal laws regulating interstate commerce and airlines. And the tax on hospitals would need a two-thirds vote in the Legislature and buy-in from health care providers.

“I look at the (financing) as throwing some ideas on the table to start a discussion,” Jacobs said.

Other proposed measures and analyses put different cost estimates for getting California closer to universal coverage. A report released this month by Covered California found that providing more financial assistance to consumers to buy plans would cost between $2.1 billion and $2.7 billion a year.

One bill, AB-4, proposes expanding Medi-Cal to all undocumented adults — a move the Legislative Analyst’s Office has estimated would cost $3 billion annually. Another bill, AB-174, aims to provide financial assistance to those making between $48,000 and $72,000 to buy insurance. It would cost $40 million to $75 million a year, according to estimates included in a previous bill.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed budget included expanding Medi-Cal coverage to undocumented young adults between ages 19 and 25, and providing state-funded financial assistance to help Californians buy insurance — both of which would be steps toward universal coverage in the state. It is unclear how much the initiatives would cost.