A defining symbol of a profession may also be teeming with harmful bacteria and not washed as often as patients might hope.

A recent study of patients at 10 academic hospitals in the United States found that just over half care about what their doctors wear, most of them preferring the traditional white coat.

Some doctors prefer the white coat, too, viewing it as a defining symbol of the profession.

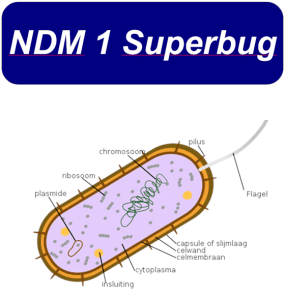

What many might not realize, though, is that health care workers’ attire — including that seemingly “clean” white coat that many prefer — can harbor dangerous bacteria and pathogens.

A systematic review of studies found that white coats are frequently contaminated with strains of harmful and sometimes drug-resistant bacteria associated with hospital-acquired infections. As many as 16 percent of white coats tested positive for MRSA, and up to 42 percent for the bacterial class Gram-negative rods.

Both types of bacteria can cause serious problems, including skin and bloodstream infections, sepsis and pneumonia.

It isn’t just white coats that can be problematic. The review also found that stethoscopes, phones and tablets can be contaminated with harmful bacteria. One study of orthopedic surgeons showed a 45 percent match between the species of bacteria found on their ties and in the wounds of patients they had treated. Nurses’ uniforms have also been found to be contaminated.

Among possible remedies, antimicrobial textiles can help reduce the presence of certain kinds of bacteria, according to a randomized study. Daily laundering of health care workers’ attire can help somewhat, though studies show that bacteria can contaminate them within hours.

Several studies of American physicians found that a majority go more than a week before washing white coats. Seventeen percent go more than a month. Several London-focused studies had similar findings pertaining both to coats and ties.

A randomized trial published last year tested whether wearing short- or- long-sleeved white coats made a difference in the transmission of pathogens. Consistent with previous work, the study found short sleeves led to lower rates of transmission of viral D.N.A. It may be easier to keep hands and wrists clean when they’re not in contact with sleeves, which themselves can easily brush against other contaminated objects. For this reason, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America suggests clinicians consider an approach of “bare below the elbows.”

With the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer — often more effective and convenient than soap and water — it’s far easier to keep hands clean than clothing.

But the placement of alcohol-based hand sanitizer for health workers isn’t as convenient as it could be, reducing its use. The reason? In the early 2000s, fire marshals began requiring hospitals to remove or relocate dispensers because hand sanitizers contain at least 60 percent alcohol, making them flammable.

Fire codes now limit where they can be placed — a minimum distance from electrical outlets, for example — or how much can be kept on site.

Hand sanitizers are most often used in hallways, though greater use closer to patients (like immediately before or after touching a patient) could be more effective.

One creative team of researchers studied what would happen if dispensers were hung over patients’ beds on a trapeze-bar apparatus. This put the sanitizer in obvious, plain view as clinicians tended to patients. The result? Over 50 percent more hand sanitizer was used.

Although there have been fires in hospitals traced to alcohol-based hand sanitizer, they are rare. Across nearly 800 American health care facilities that used alcohol-based hand sanitizer, one study found, no fires had occurred. The World Health Organization puts the fire risk of hand sanitizers as “very low.”

An article in The New York Times 10 years ago said the American Medical Association, concerned about bacteria transmission, was studying a proposal “that doctors hang up their lab coats — for good.” Maybe one reason the idea hasn’t taken hold in the past decade is reflected in a doctor’s comment in the article that “the coat is part of what defines me, and I couldn’t function without it.”

It’s a powerful symbol. But maybe tradition doesn’t have to be abandoned, just modified. Combining bare-below-the-elbows white attire, more frequently washed, and with more conveniently placed hand sanitizers — including wearable sanitizer dispensers — could help reduce the spread of harmful bacteria.

Until these ideas or others are fully rolled out, one thing we can all do right now is ask our doctors about hand sanitizing before they make physical contact with us (including handshakes). A little reminder could go a long way.