Insurers have said the move will destabilize the individual market and increase premiums by at least 20 percent.

In a move insurers have long said would destabilize the individual market and increase premiums by at least 20 percent, the Department of Health and Human Services late Thursday ended cost-sharing reduction payments.

At least one state attorney general, AG Eric Schneiderman of New York, has said he would sue the decision. The court granted a request to continue funding for the subsidies, Schneiderman said.

California may also sue the administration over the decision.

“I am prepared to sue the #Trump Administration to protect #health subsidies, just as when we successfully intervened in #HousevPrice!” California AG Xavier Becerra tweeted Thursday night.

In May, Schneiderman and Becerra led a coalition of 18 attorneys general in intervening in House v. Price over the cost-sharing reduction payments.

The cost-sharing reductions payments will be discontinued immediately based on a legal opinion from Attorney General Jeff Sessions, said Acting HHS Secretary Eric Hargan and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma.

“It has been clear for many years that Obamacare is bad policy. It is also bad law,” HHS said. “The Obama Administration, unfortunately, went ahead and made CSR payments to insurance companies after requesting – but never ultimately receiving – an appropriation from Congress as required by law. In 2014, the House of Representatives was forced to sue the previous Administration to stop this unconstitutional executive action. In 2016, a federal court ruled that the Administration had circumvented the appropriations process, and was unlawfully using unappropriated money to fund reimbursements due to insurers. After a thorough legal review by HHS, Treasury, OMB, and an opinion from the Attorney General, we believe that the last Administration overstepped the legal boundaries drawn by our Constitution. Congress has not appropriated money for CSRs, and we will discontinue these payments immediately.”

Trump tweeted this morning, “The Democrats ObamaCare is imploding. Massive subsidy payments to their pet insurance companies has stopped. Dems should call me to fix!”

Insurers reached and America’s Health Insurance Plans did not have an immediate comment on the ending of the subsidies.

The move to end CSRs comes weeks before the start of open enrollment on Nov. 1, but many insurers had submitted rates reflecting the end of the subsidies that allowed them to offer lower-income consumers lower deductibles and out-of-pocket costs.

America’s Essential Hospitals said it was alarmed by news of administration decisions that could create turmoil across insurance markets and threaten healthcare coverage for millions.

“This decision could leave many individuals and families with no options at all for affordable coverage,” said Bruce Siegel, MD, CEO of America’s Essential Hospitals. “We call on Congress to immediately shore up the ACA marketplace and to work in bipartisan fashion, with hospitals and other stakeholders, toward long-term and sustainable ways to give all people access to affordable, comprehensive care.”

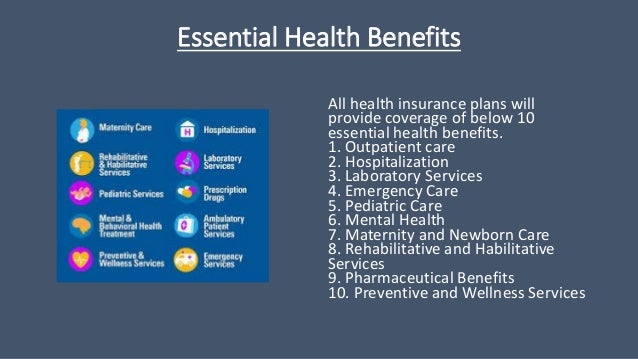

Today’s CSR decision follows yesterday’s executive order from President Trump to allow for association health plans that could circumvent Affordable Care Actmandates on coverage. The executive order must go through the federal rulemaking process and may also face legal challenges.

AHIP was swift to react to Trump’s order.

“Health plans remain committed to certain principles. We believe that all Americans should have access to affordable coverage and care, including those with pre-existing conditions. We believe that reforms must stabilize the individual market for lower costs, higher consumer satisfaction, and better health outcomes for everyone. And we believe that we cannot jeopardize the stability of other markets that provide coverage for hundreds of millions of Americans,” said spokeswoman Kristine Grow. “We will follow these principles – competition, choice, patient protections and market stability – as we evaluate the potential impact of this executive order and the rules that will follow. We look forward to engaging in the rulemaking process to help lower premiums and improve access for all Americans.”

The American Academy of Family Physicians and five other medical associations representing more than 560,000 doctors have expressed serious concerns over the effect of President Trump’s executive order directing federal agencies to write regulations allowing small employers to buy low-cost insurance that provides minimal benefits.

In a joint statement, the AAFP, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Physicians, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Osteopathic Association and the American Psychiatric Association strongly rejected the order they said would allow insurers to discriminate against patients based on their health status, age or gender.

Republicans tried to repeal and replace the ACA, and since that failed are trying to end consumer protections under the law, according to U.S. Representative Bill Pascrell Jr., a Democrat from New Jersey and a member of the Ways and Means Committee.

“Republicans have been on the warpath trying to end important consumer protections that the ACA affords, including protections for people with pre-existing conditions and required coverage for services that people actually need, like mental health care,” Pascrell said. “Now that they’ve failed in that endeavor, the Trump Administration is trying to use the back-door with this executive order.”

A Congressional Budget Office analysis released in August said the CSRs, which cost an estimated $7 billion a year, could end up costing the federal government $194 billion over a decade.