Are implants for opioid addicts a new hope or a new scam?

If a stake could be driven through the vampire heart of the nation’s opioid epidemic, it might look something like this: Four tiny spines, each smaller than a matchstick, sunk into a drug addict’s upper arm.

These implants remain beneath the skin for months, delivering a continuous dose of a drug called buprenorphine, which blunts the euphoria of an opioid high. Ideally, its manufacturer says, patients will get the implants replaced every six months, helping achieve the lasting sobriety that currently eludes an estimated 2.5 million Americans who are addicted to heroin or other opioids.

As the addiction crisis grows, implants that deliver buprenorphine, naltrexone and opioid-blocking drugs like them might offer light in an otherwise oppressive darkness. One recent study found that nearly 86 percent of the people who used the buprenorphine implant refrained from using opioids during a six-month window. And in Russia, more than half of heroin-addicted patients who got a naltrexone implant were abstinent over a six-month clinical trial.

But here in Southern California — a region known as Rehab Riviera because there are so many drug and alcohol recovery centers — implants might also be a new way to turn an illicit buck.

In one of the latest twists on the profit-before-patient mindset so common in the addiction treatment industry, addicts are demanding to be paid for agreeing to get implants, knowing that rehab centers and the doctors who surgically insert the devices can bill insurance providers thousands of dollars per patient, according to professionals in the rehab industry.

“Hey Bud. I have at least me and 3 other people looking to come … and all 4 of us want the implant,” said a text from an addict to an executive with New Existence Treatment Center in Fountain Valley, according to screen shots of a text exchange reviewed by the Southern California News Group.

“If I can get others with the same insurance any chance I could possible (sic) make little something, I got nothing… ”

Requested payouts for agreeing to the treatment, according to an apparently unsent text on the addict’s phone, were $700 for his implant plus $300 for each additional person he recruited to get implants.

Dylan Walker, one of New Existence’s owner-operators, was trading texts with the addict, and said he did nothing irregular. “If you actually read them, nowhere in there does it say I’m paying clients to get the implant,” Walker said when contacted about the exchange.

Later, in a prepared statement, the company said Walker simply offered encouragement and support to a former client, nothing more.

“New Existence has not and will not engage in any unlawful or unethical treatment or business practice such as payments to clients or other organizations for procedures or treatments,” it said by email.

“Unfortunately, the addiction treatment industry is fraught with questionable practices, and we have encountered similar requests or demands in the past—which have all been rejected.”

New Existence — a non-medical enterprise — also said it is carefully reviewing its own policies and procedures “to ensure that our communication with clients regarding treatment are clear, making sure that they understand their treatment plan as it relates to their own recovery process.”

Other addiction professionals say such demands aren’t unusual. Paying addicts to get implants – and other forms of insurer-covered treatments – is at least widespread enough to prompt some addicts to make the request.

“Does it surprise me? No. That’s part of toxic behavior.,” said Cynthia Moreno Tuohy, executive director of the National Association for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors.

The requests amount to, “Give me money to help me help you get money,” she said, and they constitute a basic corruption of how the industry should work.

“In our code of ethics, you can’t do that.”

Probuphine — the brand name of the implant that delivers buprenorphine — was developed by Braeburn Pharmaceuticals of New Jersey with partner Titan Pharmaceuticals in San Francisco. Company officials didn’t say if they’ve heard of the shakedown proposed by the addict, but promised to probe further.

“We take all reports of potential misconduct, violations of internal Braeburn policy or applicable laws, very seriously,” said Braeburn spokeswoman Nancy Leone by email.

Officials with BioCorRx, the Anaheim company that’s working on FDA approval for implants delivering naltrexone, said they have received demands for money directly from addicts.

“We have an 800 number and people just flat-out ask, ‘How much will you pay me to get your implant?’ ” said Brady Granier, the company’s chief executive. “We tell them we don’t treat people, and the people we work with don’t do that. It shouldn’t be happening.

“It’s a form of patient-brokering,” he added. “And it gives what we do a bad name.”

Naltrexone implants are inserted into the abdomen and last several months. They’ve been widely used in Europe for years and have been prescribed in the U.S. as well, even without the FDA’s official stamp of approval – which is usually required before health insurers will agree to pay for them.

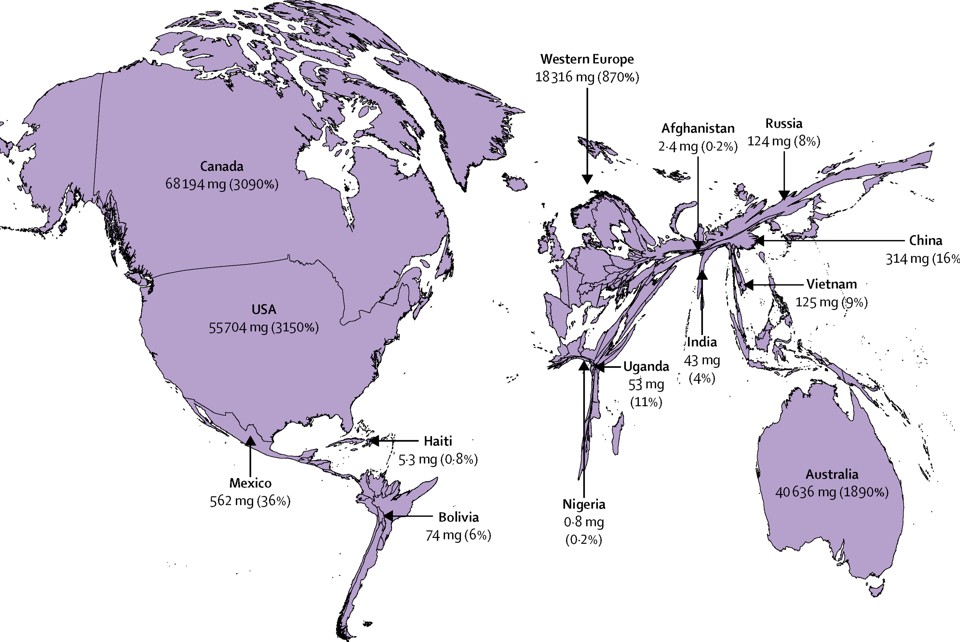

The chatter is that some illicit implants are imported from overseas, Granier said.

“There’s a black market for them. Patients who are considering this should always ask their doctor, ‘Where are you getting your implants?’”

Billing opportunity

Probuphine is, for now, the only long-acting FDA-approved implant for opioid addiction. It got the green light last year, hit the market in January, and lasts six months.

A single Probuphine implant costs $5,000, and billings for follow-up care can run thousands more. It’s covered by most private and public health insurance plans and, in a recent statement, the FDA backed such coverage, saying “expanded use and availability of medication-assisted treatment is a top priority of federal effort to combat opioid epidemic.”

Since most insurance companies don’t cover naltrexone implants yet, those are often billed as surgeries, insiders said.

Health insurance officials confirmed that they’ve heard of irregularities connected to anti-opioid implants. Many insurers and treatment providers are embroiled in lawsuits over alleged billing fraud on other fronts, and insurers claim they’ve seen all manner of creative billings in the addiction treatment industry.

“We have heard anecdotally of a California facility that makes its own implants… for use with its clients,” said Mark Slitt, spokesman for Cigna. “We would not cover that.”

Ashton Abernethy of AVA medical billing, a Costa Mesa company that works with behavioral health centers, said she started hearing about pay-for-implants scams over the last 18 months or so.

Abernethy, who said she works with rehab operators to help them understand the law, said the implant situation reminds her of the “sweaty palms” surgeries of about a decade ago. In those operations, doctors paid people with generous insurance policies to undergo unnecessary surgeries. Authorities later said the schemes generated $154 million in fraudulent billing.

The Southern California News Group recently investigated the addiction industry and found it peppered with financial abuses that bleed untold millions from public and private pockets, can upend neighborhoods and often fails to set addicts on a path to sobriety. The revolving door between detox centers, treatment facilities, sober living homes and, often, the streets generates huge money for operators who know how to game the system. And even obvious fixes prohibiting patient brokering can be hard to enact.

Some professionals in the industry, frustrated by what they see as abuses, are trying to force change from within.

David Skonezny created “It’s Time for Ethics in Addiction Treatment,” a closed Facebook group for industry professionals that has more than 2,000 members. It’s a destination for people to challenge themselves and have honest dialogue about ethics in the industry, he said, and where people are calling out what they deem as questionable behavior.

News of the pay-for-implant texts recently created a social media firestorm.

“Changing the face of addiction treatment needs to happen, and I’ve jumped on the grenade to do that,” said Skonezny, a certified drug and alcohol counselor who has served on the board of directors for California Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals.

“I’m ether in the process of doing really good work, or committing career suicide.”

Why implants?

Walter Ling, professor of psychiatry and founding director of the integrated Substance Abuse Programs at UCLA, says most people don’t really understand how much time drug addicts think about getting drugs.

It’s on their minds constantly.

When the freeway collapsed during the 1994 Northridge quake, he said, the panic for some addicts wasn’t about houses falling; it was about being unable to get to the local methadone clinic, where they could get at least a substitute for heroin.

The power of long-acting anti-opioid implants, he said, is that they can interrupt that pattern.

“Anything that can free (addicts) from the constant preoccupation with (their drug of choice) allows them to think about getting a life,” said Ling.

Implants can offer a consistency that’s lacking in other medications aimed at preventing relapse, he said. Methadone, the best known anti-opioid drug, must be taken daily and essentially marries an addict to a methadone clinic. Naltrexone blocks the effects of opioids by turning off pleasure receptors, and patients often hate it. Buprenorphine, Ling said, strikes something of a middle ground.

The current delivery systems for most of these drugs are pills or under-the-tongue film strips that a patient must keep in the mouth for 15 minutes, one or more times a day, to get the full dose. Addicts often grow weary of the routine and drop out. Pills and strips also become a commodity on the street, bought and sold from one addict to another.

Injectable drugs taken weekly or monthly, and implants, offer potential solutions to those problems. The addict isn’t making a daily decision about taking the anti-opioid, reducing the odds of relapse though not entirely wiping it out. Also, injections and implants can be invisible, meaning sobriety doesn’t include the stigma of visiting a methadone center or popping pills every day.

The manufacturers claim this helps addicts keep jobs, take care of their families and lead productive lives.

Ling is inclined to agree. He was the lead researcher on a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2010, which found that buprenorphine implants were indeed effective in treating opioid dependence over the six months following implantation.

“Of particular clinical importance are the favorable urinalysis toxicology results and the good patient retention—with 65.7% of patients who received the active implants completing 24 weeks of treatment without experiencing craving or withdrawal symptoms that necessitated withdrawal from the study,” the study said.

Naltrexone implants worked wonders as well. “The implant device, which releases a steady dose of naltrexone continuously for two months, averted relapse to heroin use three times as effectively as daily oral doses of the medication,” said the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Drug abusers are notoriously ambivalent, said study co-leader Dr. George Woody, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, in a NIDA statement. Just because they decide to quit using heroin one week doesn’t mean they’ll be motivated to quit a week later. The rationale for extended-release implants is to protect against that ambivalence.

The implants’ success in preventing relapse cuts a marked contrast to traditional social-based treatment approaches. Addicts have a relapse rate between 40 and 60 percent, according to the U.S. Surgeon General’s most recent probe, and it can take as long as 8 or 9 years to achieve sustained recovery.

Taking medication is the best guarantee that you don’t die from an overdose and actually stay off drugs, Ling said. “You can’t get a life if you can’t stay off drugs. And you can’t stay off drugs for long if you can’t get a life.”

Michael M. Miller, past president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine and medical director of the Herrington Recovery Center at Rogers Memorial Hospital in Wisconsin, also likes the idea of making it easier for an addict to get medicine for treatment, but says implants are only one way to do that. He is on the manufacturer’s physicians advisory committee for Probuphine, a paid position, but has not yet prescribed it.

“Implants probably have a role, but probably a fairly small role,” Miller said. “The 30-day injectables are going to have tremendous impact.”

On the street, stories about addicts who’ve cut implants out of their skin so they can get high are not uncommon, and some physicians worry about potential complications.

Both Miller and Ling said many in the addiction field resist the idea of using drugs as a long-term treatment. That patients might need to be on medication for the rest of their lives to manage their addiction makes physicians and patients uncomfortable; Ling chalks it up to a strain of Puritanism that runs through American culture.

Moreno Tuohy, executive director of the NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals, believes that medication is one piece of the treatment puzzle, but that counseling is essential to address the psychological, social and spiritual aspects of an addict’s behavior.

Medications may make patients more available to do the work they need to do in counseling to fully recover, she said. She also predicted that the number of medications designed to fight opioid and other addictions is going grow considerably over the next few years.

“The hope is it will help people to reduce cravings for marijuana and cocaine and other drugs, and become more available to comprehensive treatment,” Moreno Tuohy said. “That’s the goal, not just (short-term) recovery.”