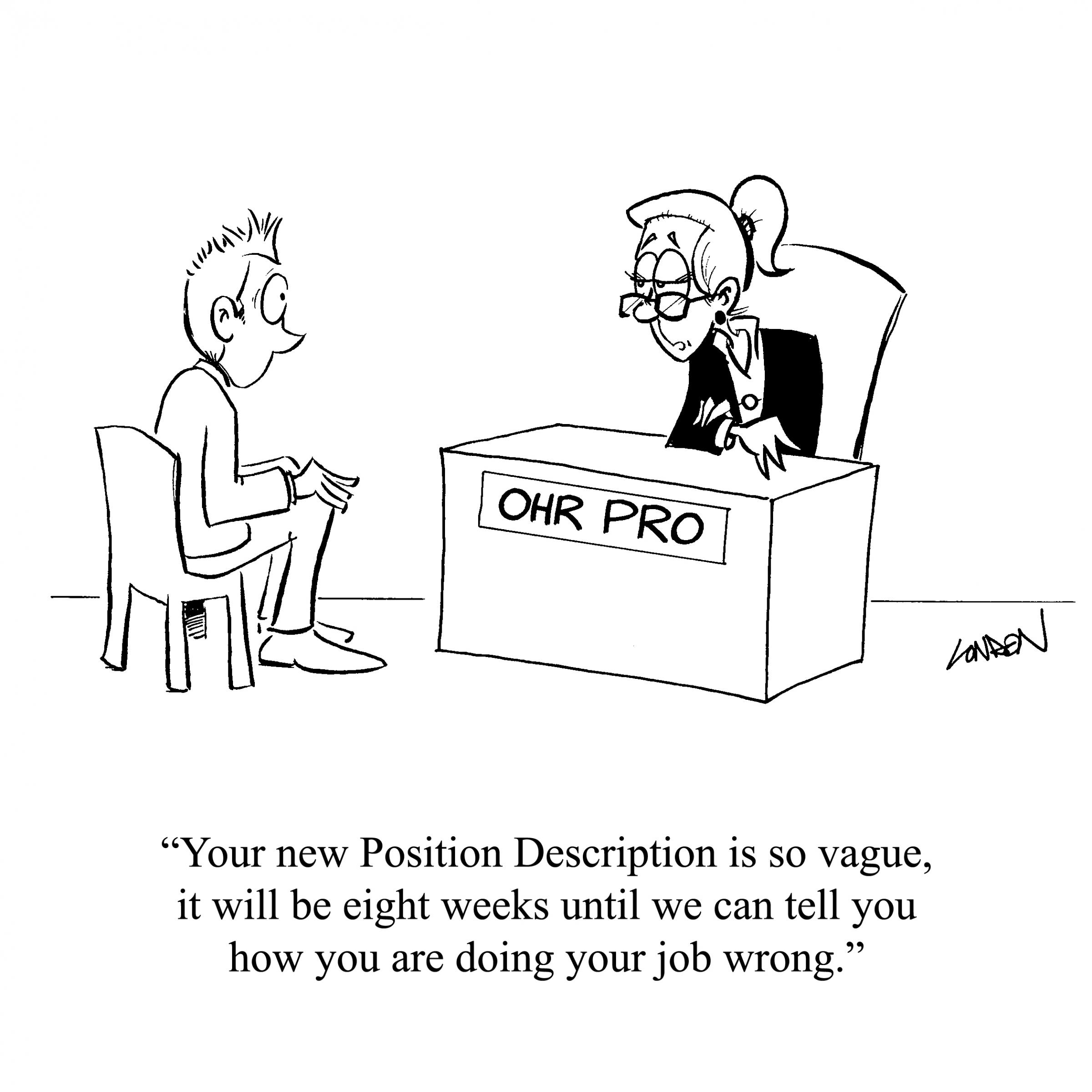

Cartoon – Importance of Reinvention in Today’s Job Market

Nursing and physician shortages aren’t the only staff challenges providers are facing. According to a new STAT poll from the Medical Group Management Association, a majority of healthcare organization leaders said their group can’t find enough qualified applicants for non-clinical positions either.

The poll was conducted on May 1, 2018 with 1,299 applicable responses.

More than 60 percent of respondents said their organizations had a hard time recruiting non-clinical staff. The reasons include larger organizations offering better pay, low unemployment rates and difficulty recruiting in rural areas. One respondent said “recruiting millennials is a completely different game” and another cited lack of future career advancements in the billing and coding field.

“Lack of medical training in colleges and technical schools and reliance on ‘on the job training’ means less qualified non-clinical applicants,” MGMA said.

Other reasons include competition from other medical groups, hospitals and health systems as well as competitive pay from other industries that trigger turnover.

One-third responded they haven’t experienced this shortage, citing low turnover. Those respondents also said they had increased wages to retain staff, MGMA said.

A past poll has shown this high-turnover is prevalent in front-office staff, which some experts have argued are the face of a practice and the first ones to interact with patients, often setting a tone for the care episode making it a crucial influence of patient satisfaction.

When there is high turnover, new employees are often not as well-versed in office policies and procedures because they likely haven’t been there very long. This can lead to mistakes, inaccuracies and bumpy interactions with patients who expect staff to know operations inside and out. It can also lead to costly errors not just on the part of new employees, but veteran staff who are busy training and juggling multiple tasks at any given moment. The trickle down effect could mean patients wait longer to be seen, appointments go longer and collections and claims may be riddled with mistakes.

Medical group leaders know that it isn’t just doctors and nurses who make their practices successful and run smoothly, so they would be well-advised to treat retention of non-clinical staff with urgency.

Since a third of respondents reported lower turnover after raising wages for non-clinical staff, decision-makers for practices may want to consider researching current competitive rates for these positions and potentially raising wages such that staff would be less inclined to seek higher-paying employment elsewhere.

Practices also might consider how else to boost employee benefits and the workplace environment so that employees experience greater satisfaction. Turnover leads to operational hiccups, less efficient service for patients and lower satisfaction rates.

“While finding qualified candidates is a challenge for medical groups, practice leaders can begin by assessing how they are approaching retention of their best employees and mitigating turnover before it becomes an issue,” MGMA said.

http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180505/NEWS/180509944

Sending a senior executive off-site to expand his perspective was part of the Cincinnati-based health system’s leadership institute, which aims to develop the skills of some 1,000 administrative and physician executives and prepare them for new roles.

While many executives move around within their organization’s network, the approach aimed to expose the employee—who had spent much of his career at TriHealth—to another corporate culture and operations.

“We obsess about spending $2 million on a CT scanner, but we can’t find a way to spend $10,000 on investing in our leaders,” said TriHealth CEO Mark Clement, who launched the system’s leadership institute about ½ years ago. “I would argue that investments on improving talent within our organization produce dividends far greater than a piece of equipment.”

For many providers, it’s the end of an era. Hospital, health system and physician group executives are seeking new leaders. They are prompted by an exodus of top healthcare executives, a generational transfer of power highlighted by the departures of senior managers like Dr. Toby Cosgrove, former Cleveland Clinic CEO; Michael Murphy, CEO of Sharp HealthCare who is retiring in 2019; and outgoing Mayo Clinic CEO Dr. John Noseworthy.

Organizations are actively searching for what’s next and who will take them there. Industry consolidation is accelerating that conversation. But there is wide variation on their approach and level of preparation.

There’s a lot at stake, both from a cultural and financial perspective, said Mark Armstrong, vice president of consulting operations at Quorum Health Resources. Good managers translate to engaged employees, he said.

But only about 33% of U.S. workers are actively engaged in their jobs, and a mere 15% of employees strongly agree the leadership of their organization makes them enthusiastic about the future, according to a 2016 poll by Gallup. The firm estimates that disengaged employees cost the U.S. $483 billion to $605 billion each year in lost productivity.

“Even when systems know someone is retiring, it is interesting how few of them still don’t have an assertive plan in place,” Armstrong said. “Any kind of turnover can be disruptive, especially if there has been a trend of declining performance. It’s not unusual for a ratings agency to have heightened concerned when a CEO leaves.”

Almost every system grapples with a huge retention problem, which can make it difficult to plan ahead, said Alan Rolnick, CEO of Employee Engagement and Retention Advisors. The most costly departures are often experienced nurses, he said.

“It’s not just the cost of replacement but the loss of institutional knowledge,” Rolnick said.

TriHealth’s leadership program highlights potential candidates within the system who could fill upcoming vacancies. It puts executives on a multiyear track that assesses potential areas for improvement and exposes them to systemwide quarterly leadership training sessions and other development opportunities. The company’s vice president of finance, Brian Krause, spent a week at BJC HealthCare in St. Louis, relying on connections TriHealth had with the organization. Krause is also planning on spending some time at the University of Pennsylvania Health System, as well as a few other systems.

Since launching the institute—which is conducted with the help of the consultancy Studer Group—TriHealth’s employee engagement improved from the 26th to the 74th percentile, which has helped the organization generate a 3.5% operating margin—one of its highest margins in recent history, Clement said. Its patient experience scores are also up from the 50th percentile to the 75th, helping to drive an increase in admissions, bucking the national trend.

Ideally, promoting from within will ensure cultural and operational continuity and motivate executives, Clement said. “When you bring new senior executives in from other organizations, it can be a threat to the culture,” he said. “For an organization like ours that has invested a lot of money in building a culture based on value, engaging team members and flattening the organization, it’s often best to promote from within.”

Ascension also recently launched a diversity inclusion campaign that seeks to cultivate minority leaders.

“The types of leaders are changing,” Ascension CEO Anthony Tersigni said at the American College of Healthcare Executives’ 2018 Congress on Healthcare Leadership in March. “The time for guys like me who started as a hospital operator is passing.”

The CEO of a Fortune 100 company told Tersigni several years ago that he spends about 30% of his time on leadership development. Tersigni, who at the time only spent a fraction of that on cultivating executives, said that interaction completely changed his perspective. Ascension has since partnered with a number of universities to build a better leadership curriculum and management pipeline.

“Disruption in the healthcare industry is not going to come from the hospital across the street, it has been coming from outside the industry,” Tersigni said. “We need to understand how they think, how they act, how they make decisions, because it is a lot faster than healthcare can dream of.”

Renton, Wash.-based Providence St. Joseph in 2017 partnered with the University of Great Falls in Montana, in part, to create a stable pipeline of managers to feed into the integrated health system. The university, which was renamed University of Providence, will include professional and certificate programs for Providence St. Joseph’s more than 111,000 employees.

The health system has also implemented mentoring and leadership development programs that have increased its women executive cohort by 50% over a three-year period.

“Diversity begets diversity,” said Dr. Rod Hochman, CEO of Providence St. Joseph, adding that women and minority leaders will help the system better understand its most vulnerable populations. “We are looking for folks with different perspectives who can help lead us through this time of change.”

Whether the successors are internal or external, establishing a strong executive pipeline requires a proactive and standardized approach, and the board should take the lead, industry analysts said.

A health system should identify the competencies it needs to lead the team going forward and where the gaps are, said Craig Deao, a senior leader at Studer Group. “The three keys leaders of tomorrow need to have are getting people to do things better—performance improvement; getting them to do new things—innovation; and helping people do those things—engagement,” he said.

Managing the process rather than the people will translate to more innovative and engaged employees, according to Rolnick. It starts with communication, he said.

“Today, the average employee of a hospital has no idea of the strategic direction of their organization and what their role is,” Rolnick said. “You have to tell them as much as you can, and be open and honest.”

Beyond employee engagement, executives need to understand how to interact with patients. As the industry adapts to thinking of patients as consumers, that requires a different lens, Deao said.

“People need to understand how to shape behavior and apply concepts of psychology to running the business,” he said.

Healthcare is becoming more consumer- and technology-oriented. Health systems are also focusing more on nutrition, transportation, education, fitness and other social factors that influence an individual’s health.

Novant Health, for instance, is launching a new leadership program that looks to train untapped community leaders in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C. The program involves a combination of teaching sessions and mentoring that aims to reach individuals who otherwise wouldn’t have access to programs that hone their leadership skills, said Tanya Blackmon, executive vice president and chief diversity and inclusion officer at Novant.

While there is a significant learning curve, experience in consumer insight, marketing or technology can better equip individuals to tackle healthcare’s current challenges, said David Schmahl, executive vice president of consultancy SmithBucklin and chief executive of its healthcare and scientific industry practice.

“The experience people are obtaining in leadership roles outside the healthcare field is critical,” he said.

The role of healthcare leadership has evolved into a platform used to convey a moral foundation, spanning conversations from racism to gun control. They have to balance their role as an influencer while dealing with budgets, managing their boardrooms, implementing both long-term visions and short-term goals, and maintaining an engaged workforce.

The average tenure of healthcare executives and managers is also decreasing, particularly among CEOs, nurses and physicians, which exacerbates labor shortages. A C-suite executive’s pay is still tied to financial metrics, but quality, safety and patient satisfaction are becoming a more prominent determinant.

While Novant’s initiative isn’t necessarily geared to develop successors, it signifies how the definition of a leader is evolving.

“We are looking at trying to tap talent across all spectrums,” Blackmon said. “We’re not leaving any area untapped.”

“The trend toward our hospitals being primarily populated with nurses with less than two years’ experience is worrisome.”

At least three colleagues who’ve recently been patients in hospitals or had family members who were have remarked on the youthful nurses they encountered—and on their lack of experience. In two of the conversations, my colleagues cited instances in which this lack of experience was detrimental to care, one of them dangerous. That “sixth sense,” that level of awareness that comes with lived experience and becomes part of expert clinical knowledge, is important for safe, quality patient care.

In the February editorial, I report on the answers I received when I queried our editorial board members about new nurses’ inclination to work in acute care for only two years to gain experience and then leave to pursue NP careers. Many of the board members have seen a similar trend, one reflected by research on nurse retention, some of it published in AJN (most recently, see Christine Kovner’s February 2014 study on the work patterns of newly licensed RNs, free until February 6).

As one board member noted:

“The narrative must be shifted to embrace the full range of roles and contributions of all nurses. Our health care system depends upon a well-trained, experienced workforce. The trend toward our hospitals being primarily populated with nurses with less than two years’ experience is worrisome.”

It’s a complex issue, and no one is faulting new RNs for the career paths they pursue. But as this trend accelerates, what can be done to ensure that there are enough experienced nurses at the bedside to protect patient safety? Let us know your thoughts.

Few roles are as important as the chief financial officer at most companies, but the CFOs today who are thinking about tomorrow are growing nervous about a key talent issue. They just don’t think anyone else in the company can assume their role.

Indeed, according to a new Korn Ferry survey, 81% of CFOs surveyed say they want to groom the next CFO internally, but they don’t believe that there’s a viable candidate in-house. Currently, about half of new roles are filled internally.

“The current CFO is the one charged with identifying and developing that talent, and since they know best the skills required to meet what’s coming, they are realizing the internal bench isn’t fully prepared,” says Bryan Proctor, senior client partner and Global Financial Officers practice lead at Korn Ferry.

The lack of confidence is owed in part to CFOs feeling that their firms’ leadership development programs haven’t kept up with the rapidly changing role of CFO. Core functions such as finance and accounting are increasingly being combined under one role, with CFOs citing a lack of resources or skills and career development opportunities as reasons for the merging. Korn Ferry surveyed more than 700 CFOs worldwide, asking them about their own internal talent pipelines. The top two abilities CFOs feel their direct reports need to develop are “leadership skills and executive presence” and “strategic thinking.”

“The tapestry of skills and experiences CFOs of today and tomorrow need are vastly different than what was needed in the past,” says John Petzold, senior client partner and CXO Optimization lead at Korn Ferry. “The reason subfunctions are merging is because the focus is less on a role or person and more about the capabilities that need to be covered by a set of individuals.”

In essence, the CFO function is being deconstructed for optimization. Leaders are breaking down necessary functions based on their organization’s strategy and identifying people with a combination of those skills and piecing them together to get the right set of talent to execute against that plan. Core financial functions such as taxes, capital allocation, and M&A still need to be done accurately and in compliance with regulations, of course. But experts say the CFO role is becoming more about adapting and deploying talent in the most efficient manner possible.

“The leadership profile of the future CFO is less about tactical, direct experience, and more about learning agility, adaptability, and big-picture global perspective,” says Proctor. “That kind of nimbleness and ability to pivot isn’t naturally ingrained in the typical CPA.”

So far in 2018, approximately 12 hospital and health system executives have suddenly left their roles. While there are myriad reasons for the departures — ranging from being ousted to personal issues — most of them occurred with little or no notice. Whatever the reason, the question remains: How can executives mitigate the potential fallout?

According to Cody Burch, executive vice president at healthcare executive consulting and search firm B.E. Smith, any potential fallout from a sudden departure can be mitigated if executives remain positive and transparent.

“It doesn’t necessarily have to have a negative impact on [a] healthcare executive’s chances of landing another job,” he says.

There are several reasons behind a healthcare executive suddenly stepping down from their role. Common ones include burnout, termination for cause, personal issues and structural changes in the organization, says Mr. Burch. More recent reasons include consolidation, facility closures and demand for new skill sets. An executive may find they are not the right fit for the role anymore as the demands of the role or organization have changed.

An executive who has suddenly left an organization may find they have fewer opportunities in the job market. Mr. Burch says sometimes organizations looking to fill positions may only consider candidates who are currently employed, so executives who have recently left their roles may see a narrower job market than before.

Job seekers with a sudden departure on their resume may have to navigate challenging waters as they look for new opportunities. Here are five key considerations for these executives:

1. Remember honesty is key. Healthcare is very well connected. Healthcare executives and recruiters know each other, often having crossed paths over several years working in the same industry. The best strategy for executives who are looking for a new job after an abrupt departure is to be honest about their past circumstances.

“It is easy for people to find out the real story in an industry like healthcare,” says Mr. Burch. “Communicate about it honestly.”

2. Proactively address the one question every recruiter will ask. Most recruiters will ask the inevitable question, namely some version of, “Why did you leave your previous role?” Mr. Burch suggests healthcare executives expect that question and address it before the recruiter can even ask it. This gives the executive control over the messaging and narrative.

Mr. Burch says executives need to prepare their response to the question carefully. As much as possible:

• Try to disconnect the reason you are no longer in your previous role from the future.

• Communicate what you learned from your previous experience.

• Keep your answer short and focused on the positives.

• Reiterate your qualifications for the current opportunity.

• Explain why you are great fit for the new organization.

3. Stay positive. Although an abrupt departure can be a negative experience, it is important not to lose your positivity and perspective. “I think there is something to be said for either [the executive] or the employer identifying that the fit just isn’t there in the current organization,” says Mr. Burch. “Being able to come to a conclusion and reflect, truly reflect, on why it didn’t work.”

Finding an organization that is a better fit for the executive is a good thing for both the executive and the organization. It is important not to become bitter or emotional. Take the high road regardless of how things ended with the previous employer.

4. Keep networking. Keep your CV up to date and leverage your relationships within the industry, Mr. Burch says. Networking is always critical, but especially so at times of sudden change. Don’t be afraid to ask for help with your CV and partner with a recruiting firm if needed, he adds.

5. Leverage interim leadership. Executives looking to get back into the industry after a sudden departure can look for interim leadership roles. Use these roles to build confidence and demonstrate their value, says Mr. Burch. This will also help connect you to new people within the industry and potentially, new advocates for your leadership expertise.

“If you handle that transition well and get into a good opportunity for your career, the transition no longer matters,” says Mr. Burch. “People aren’t going to look back at that situation unless it happens commonly and frequently [in your career].”