https://hbr.org/2017/10/the-critical-skills-for-leading-major-change-in-americas-health-system

At a time of profound volatility in the U.S. health system, change management is an essential skill for public and private leaders alike. For these leaders — and young people aspiring to careers as health care managers — one very practical question emerges: What are the critical skills for leading major change in our health system?

As someone who has led large change management projects in both the federal government and a large private health system, my view is that effective leadership of fundamental change requires the following: a commitment to transparency; involving stakeholders so they feel that their voices are heard; making listening a personal priority of the leader; going overboard in communicating; emphasizing that the sought-after change is achievable; and developing a motivating narrative.

Two personal stories illustrate these points.

The first concerns the challenge of creating the meaningful use program for the HITECH Act when I served as national coordinator of health information technology from 2009 to 2011, at the beginning of the Obama administration. The second involves the task of replacing the electronic health record system (EHR) at Harvard-affiliated Partners HealthCare, the largest health system in New England. The latter was a project I led after returning to Partners in 2011. This was a $1.2 billion capital investment, the biggest in the organization’s history.

Both challenges were fundamentally political with a small “p.” And the road to success was in many ways the same.

The HITECH Act, which was part of the federal stimulus program enacted in response to the financial crisis of 2008, tasked the Obama administration and its Department of Health and Human Services with creating a nationwide, interoperable, private, and secure electronic-health-information system. The president made this goal even more formidable by promising that every American would have an electronic health record by 2014.

The HITECH Act provided a wide array of authorities:

- As much as $30 billion in new spending under Medicare and Medicaid. This was for incentive payments and supplemental reimbursement for services provided by health professionals and hospitals that became meaningful users of IT.

- $3 billion in discretionary spending authority for the national coordinator to set up the national infrastructure needed to support and facilitate the adoption and meaningful use of EHRs.

- Authority to write new regulations defining meaningful use of these systems, creating a certification process for EHRs, and specifying standards that would enable records to support meaningful use, as defined by regulation.

The HITECH Act also included constraints — many about timing. Regulations setting out standards had to be issued within about nine months from the time I arrived. Furthermore, payments to providers for conforming to meaningful use were to be available under the law in less than two years — by January 1, 2011. So any infrastructure supports to assist providers in becoming meaningful users had to be in place very fast — by early 2010 at the latest.

Still another constraint — one of those important details that are appreciated by students of management — was that the Office of the National Coordinator that I inherited was tiny (a total of 35 FTEs) and had never written a regulation or made a grant before. There was, for example, no grants-management office even though we were expected to rapidly expend $3 billion in infrastructure grants and contracts to prepare the nation for meaningful use.

Though the implementation of the HITECH Act seemed superficially like a technology project, I gradually came to realize that it was much more than that. Nothing in the law required hospitals or doctors to adopt or meaningfully use electronic health records. They had incentives to do so, but they could easily refuse.

In fact, we were actually engaged not in a technology-implementation program but in a huge change-management initiative. We had to convince hundreds of thousands of health professionals and thousands of hospitals and hospital managers to take on the difficult, complex, costly, disruptive, and frustrating task of changing the way they managed what is arguably the most critical resource used in daily patient care: information. We were in a contest for the hearts and minds of professionals running our health care system. This larger battle for hearts and minds conditioned everything we did in applying our authorities and meeting our practical challenges.

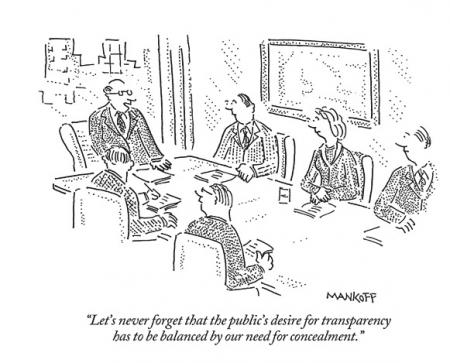

First, to create the credibility and trust we needed to lead this movement, we insisted on transparency. We formulated the meaningful-use regulation in public through a series of hearings and public deliberations, which were streamed live. Whenever we faced the option of whether to make a decision in public or private, we chose the public approach. We held scores of open meetings involving our advisory committees during the two years I was national coordinator.

Second, to deepen public trust, we made listening a priority. Understanding that people affected by government policy want to be heard, I took every meeting I could with representatives of health care stakeholders, especially physicians and hospitals. After one meeting, I got feedback about what a great exchange we had. In fact, I had said nothing at all beyond introducing myself at the outset.

Third, we communicated extensively. When we released the proposed rule, we did so with a press event in the Great Hall of the Department of Health and Human Services with a packed crowd. I then went on a national tour — to Tampa, Minneapolis, Tucson, Salt Lake City, Omaha, Burlington, Buffalo, Houston, and beyond — to explain the proposed regulation.

Fourth, we emphasized the feasibility of complying with the meaningful-use rule. We needed to make clear that becoming a meaningful user was not a superhuman task. We wanted adoption to be so manageable that non-adopters would be embarrassed among their peers at golf outings or weekend cocktail parties.

Fifth, we sought narratives — metaphors for what we were trying to accomplish — and I used them repeatedly in my speeches. The one that stuck was an escalator image: We were getting on an escalator toward increasingly sophisticated and powerful uses of EHRs. We were starting on the first step, but the rest would follow in due time.

We also spoke of inevitability. It was inconceivable, we argued, that within 10 years, physicians and hospitals would still be walled off from the information age. They could make the conversion now — with government support — or they could wait and do it on their own. But either way, they were going to have to make the change. They were going to have to get on that escalator.

The meaningful-use program has had its problems, but it did succeed in one of its most fundamental purposes: the adoption of EHRs, which are now ubiquitous in medical practice. In the end, the program got very close to fulfilling President Obama’s promise that every American would have an electronic health record by 2014.

Now let’s turn to the task of implementing a new EHR in a large operating health system that included two major teaching institutions (Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital); multiple community hospitals; a rehab hospital; a nationally-known, inpatient, psychiatric facility; a half-dozen community health centers; a home-health-care agency; thousands of community-based physicians; and the largest non-profit, private, biomedical-research program in the world.

The Partners HealthCare System was already sophisticated electronically. The problem was that it had multiple, homegrown, electronic health records onto which local physician-developer teams had layered a wide variety of specialty specific applications. The result was an electronic tower of Babel that was becoming increasingly expensive to service and modernize. But the key problem was that the records were not internally interoperable, which had become a growing barrier to improving quality and efficiency in an increasingly demanding local-health-care environment.

Before I arrived in 2011, Partners leadership had made the decision to replace all this complexity with a single, commercial EHR. It was my job to lead the process of picking one and rolling it out.

Now, though Partners was legally a single health-care-delivery system, I knew from having worked there for much of my professional life that it was in fact a loose confederation of independent institutions populated by equally independent and skeptical professionals. Winning their support, and that of managers throughout the system, was critical to success. Once again, we were battling for hearts and minds, which meant that many of the approaches we relied on in government were relevant.

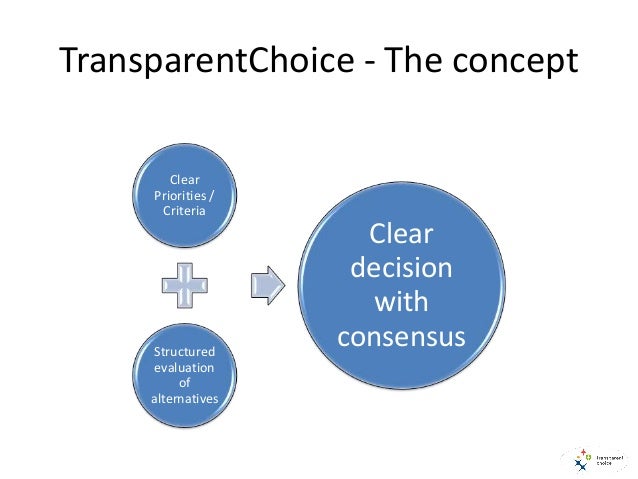

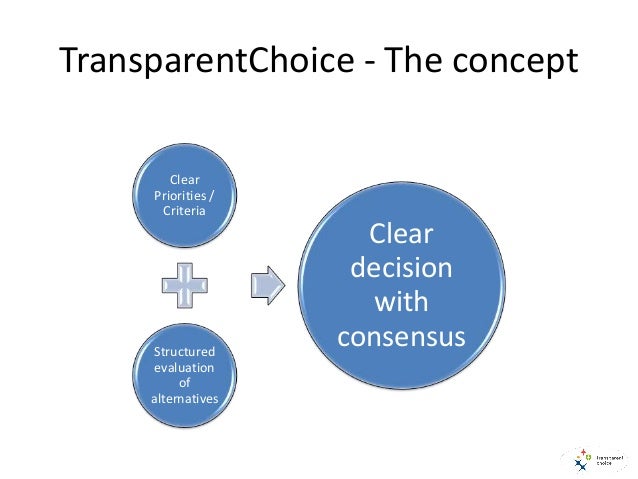

Building trust through a transparent decision process was the first strategy we pursued. The initial and critical decision we faced was which EHR to purchase. There were two finalists. To choose, we collected evidence, evaluated the alternatives, and made decisions in highly public and inclusive ways. We invited thousands of professionals to test and rate the two products. We reported the results publicly on a project website. We conducted site visits to health care organizations around the country using the products we were considering. Site visit teams were diverse and representative of major Partners institutions and stakeholders. They rated the sites’ experiences with the EHRs, using a standardized protocol. We reported results on the website.

Then, we held a public debate between advocates of the two contending records — in which teams argued about relative merits before the audience voted. The vote was highly influential in our final choice. This transparent and inclusive decision-making process included an enormous amount of built-in listening and feedback from affected staff, another critical part of the change-management process.

To address the need for inclusive governance and representative decision making, we put in place a governing council for the EHR project. Members included representatives of critical Partners institutions and stakeholder groups. This council approved all major decisions with respect to the choice of the EHR and implementation policy. We then took those approved decisions to senior management of Partners, and ultimately to the Partners board, for final endorsement. Obviously, the fact that a representative body had approved our recommendations enormously increased their weight with management and board members.

As in the case of the meaningful-use program, communication was important. It didn’t require traveling the country, but it did require visiting all the major Partners institutions to speak with their staff and management, to answer questions, and to take in feedback.

Finally, we needed a rationale and a narrative that conveyed the necessity of undertaking this admittedly expensive and disruptive change in Partners affairs. The rationale and narrative focused on the institution’s obligation to its patients. This was conveyed first in a motto: one patient, one record, one billing statement. To make this motto concrete, we made a video of a patient describing how she had had to carry a paper record from one Partners institution to another — all of which had siloed EHRs — as she got care for her breast cancer: surgery at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, chemotherapy at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and radiation at the Massachusetts General Hospital. I recall vividly the impact this video had during a presentation I made to the academic chairs of departments at Mass General. Patients’ stories had an almost unimpeachable legitimacy, even with the most senior Harvard academic leaders.

Before I left Partners to join the Commonwealth Fund in 2013, we had chosen the EHR and begun the rollout of the new IT infrastructure. While that rollout has not been perfect and, typical of such massive implementations, there have been plenty of complaints about the difficulty of using the new record, it has largely proceeded according to plan.

Change management is at the core of everything that public and private institutions are striving to achieve in reforming national policy and care-delivery approaches in order to improve the quality and cost of health care services provided daily to Americans. The effectiveness of leaders in both the public and private sectors in managing ambitious change efforts will determine their ultimate success. And my experience suggests that the skills required in these two sectors are remarkably similar — because change management, regardless of setting, involves convincing human beings to give up something they know for something new and uncertain.