Category Archives: Leadership Culture

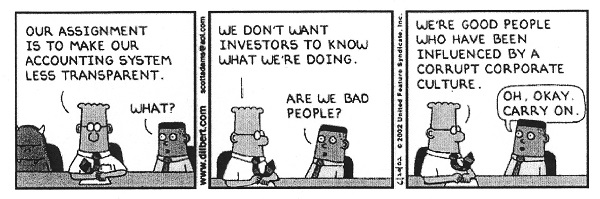

Cartoon – Questions of Ethics

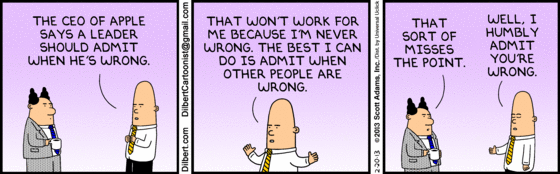

Cartoon – Importance of Culture

Cartoon – Influenced by Corrupt Corporate Culture

Don’t Let Your Hospital Be Boeing

If you haven’t noticed (but I am sure you have) American business can be very unsettling from time to time, and occasionally the bigger the business, the more unsettling it gets. Exhibit A right now for this observation is, of course, the Boeing Company.

For years Boeing was an iconic, high reliability company; a worldwide leader in the growth of airplane transportation. As Bill Saporito wrote in the January 23 New York Times, Boeings’ airplanes were industry-changing, including the 707 jet in 1957, the 747 introduced in 1970, and perhaps the most successful commercial plane in aviation history, the 737.

But when things go bad, they can, indeed, go very bad. The newly designed 737 MAX crashed twice, once in 2018 and again in 2019, with a loss of life of 346 people. Now this year, a door plug fell off the Alaska Airlines Boeing 737 Max 9 at 16,000 feet and subsequent investigation revealed the possibility of missing bolts. All 737 MAX 9s were grounded while a special investigation was convened. Manufacturing airplanes is a special enterprise; lives are at stake. Airlines and the flying public take these Boeing problems very seriously.

What went wrong at Boeing?

Everybody has an opinion. One popular interpretation goes all the way back to Boeing’s merger in 1997 with McDonell Douglas. Recent articles suggest that prior to 1997 Boeing had a very dominant “engineering” culture. After the McDonell Douglas merger, the Boeing culture took a more “business” turn. That is the speculation anyway.

What strikes me here is the similarity between Boeing and the American hospital industry. Boeing “manufactures” planes and hospitals “manufacture” healthcare.

Neither industry can make mistakes; manufacturing errors in both cases change lives and cause real personal and societal pain. For both Boeing and hospitals, high reliability and error-free execution is the only acceptable business model.

Why is this analogy to Boeing apt and important?

Because American healthcare is likely the most intricate enterprise humanity has ever engineered. Therapeutic interventions are increasingly effective but demand pinpoint diagnoses and precision treatment. All of this is happening within profound technological complexity. The opportunity for regrettable manufacturing error—in fact the likelihood of such error—is so significant that no American hospital can possibly take for granted that high reliability processes and culture are properly in place and remain in place.

So what can hospitals do to keep from being Boeing?

In all candor, this question is over my paygrade, so for an experienced and nuanced answer, I turned to Allan Frankel, MD. Dr. Frankel is an anesthesiologist and former hospital executive who founded Safe and Reliable Healthcare after evaluating one too many disasters in healthcare delivery. He is currently an Executive Principal at Vizient Inc. Dr. Frankel offered the following high reliability tutorial:

- High reliability manufacturing is directly dependent on the culture of the organization in question. Everyday excellence which leads to high reliability is dependent on the collective mindset and social norms of your workforce. Any high reliability workforce must trust its leadership and believe that the workforce values and leadership values are aligned. Further, a high reliability culture gives the workforce a sense of purpose and the opportunity to be their best professional selves on the job.

- In the workplace, bi-directional communication is essential. Leaders and managers must round, see the actual work firsthand, learn what it is like to perform the work, and talk to individuals about the challenges of doing the work. Under best practices senior leaders should round 10% to 20% of their time. Line managers should round 80% to 90% of their time.

- Workers, on the other hand, must have a sense of voice and agency. Voice means that workers are able to speak up about their concerns and ideas. Agency means that when workers do speak up, they see their ideas and concerns influence their work environment for the better.

- Voice and agency require that workers feel safe in the high reliability process and that when identifying defects in the manufacturing process, they will be treated fairly. And importantly, that having the courage to speak up is an organizational attribute that is perceived as worthy. Such worthiness is described by discrete concepts including “psychological safety,” just culture,” and “respect.” Each of these concepts is definable and requires focused and ongoing training.

- Concepts 3 and 4 require close attention and care and feeding. Functionally, this happens by robust leader rounding, robust managerial huddles, and timely feedback regarding manufacturing concerns and weaknesses. These activities need to be structural and must be built into a system of operations—such systems are often referred to as “standard work.” These changes plus the right frame of mind functionally drive improvement and change. Dr. Frankel noted “it’s not complicated, but as the Boeing example illustrates, the high reliability philosophy must be perpetually nourished.”

- Once all the above is in place, there needs to be an effector arm. Process improvement skills are required to take ideas and concerns and test and implement them. Quality personnel must check on the changes as they are being made and audit operations. Dr. Frankel adds that this part of the high reliability journey is very often under-resourced in healthcare organizations, with the result that the overall process feels less effective so the activities stop occurring.

- Training and skills are paramount. Skills come from training and reading. You should be thinking here about the “10,000 hours concept.” Worthy attitudes must be defined by your organization and then uniformly expected of all staff. Finally, behaviors can be structured, expectations set, and measures and metrics identified.

As you can see from the suggested activities, the foundations of high reliability are not rocket science. They require the right frame of mind, attention to detail, and clear accountability of all involved. No hospital should let that metaphorical 737 MAX 9 door plug fall off at 16,000 feet. It was, without question, a terrifying manufacturing moment.

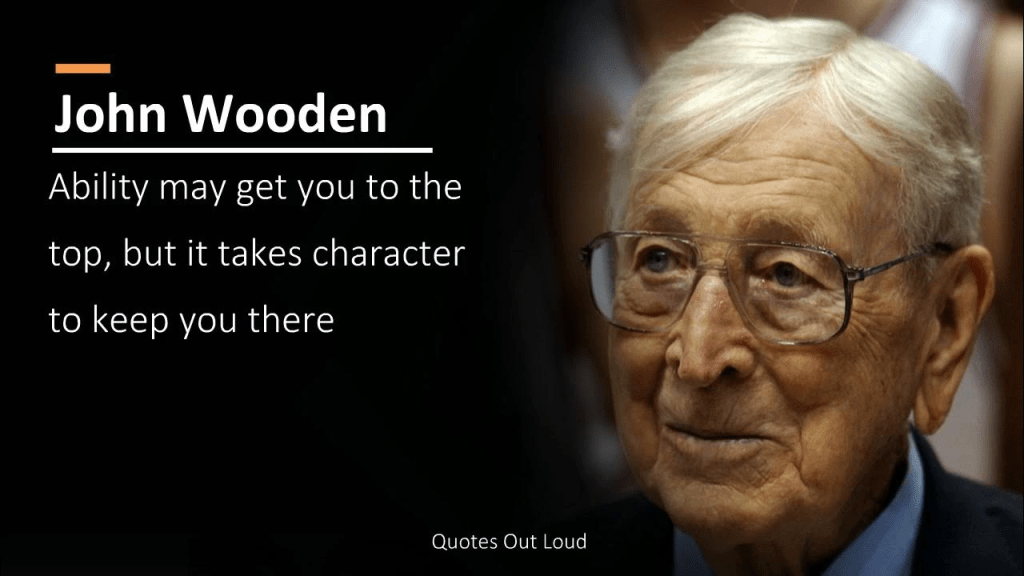

The Leadership Theories of Coach John Wooden: “Be Quick—But Don’t Hurry”

The struggle continues as hospital executives work overtime to return their organizations to necessary profitability, essential competitiveness, and offering an appropriate level of clinical access.

As noted in this blog several months ago, management guru Peter Drucker always maintained that hospitals were the hardest of all American organizations to run successfully. If Drucker were still alive, he would—without question—double down on that observation.

The question must be asked whether historical hospital leadership structures and strategies are still adequate to cope with a fast-changing healthcare industry that features a different level of financial problems, an unrecognizable workforce, and a shape-shifting patient population? This is a leadership question that requires a thoughtful and sophisticated answer.

To paraphrase Albert Einstein, we cannot solve our hospital management problems with the same level of leadership that created them.

So, we are collectively on the hunt for leadership and managerial solutions. The leadership ideas must be different, original, and challenge conventional thinking. Successful healthcare executives these days must be active readers and learners. Winning ideas are everywhere but you need to be both curious and aggressive to find them.

In that regard, let’s turn our curiosity toward the theories and teachings of Coach John Wooden. For our younger readers, John Wooden was the coach of the of the UCLA men’s basketball program from 1948 to 1975. During that time, he won 10 NCAA national championships in 12 years and at one point his teams won 88 games in a row. ESPN’s “Page 2” readers voted him the greatest coach of all time.

But John Wooden wasn’t just a basketball coach; he was a manager, an executive, a teacher, and a philosopher. There was nothing random or laissez-faire about his approach to leadership. Coach Wooden led through a series of principles that he applied with absolute consistency.

Players changed, the opposition changed, and external factors changed, but Coach Wooden’s essential approach to leadership did not vary or change.

The central tenet of Coach Wooden’s leadership philosophy was the somewhat Zen-like principle of “be quick—but don’t hurry.”

At first blush, this organizing principle doesn’t seem to make much sense, especially to the casual reader. John Wooden believed and taught that there were two keys to successful performance, both in sports and otherwise. First, quickness and a sense of urgency was absolutely necessary to winning in a competitive environment. But for Coach Wooden, quickness itself was not sufficient for consistent success. Quickness had to be accompanied by emotional and professional balance in order to achieve team and organizational excellence. So, from Coach Wooden’s perspective, a great athlete or a great executive had to not just move and think quickly, but also had to make sure that he or she was moving to a place of personal balance. Coach Wooden believed that this concept of personal balance was the key to real success at both the team and individual level. To find that place of balance you needed to be quick, but to retain that balance you had to be sure not to hurry. In other words, “be quick—but don’t hurry.”

“Be quick—but don’t hurry” was the central principle of John Wooden’s leadership style but “be quick—but don’t hurry” was also the platform on which an entire management and leadership theory was built. This led to other key Wooden tenets including:

- Focus on Effort, Not Winning. Amazingly for a coach that won 10 national championships, the UCLA players always said that Coach Wooden never talked much about winning. Instead, he talked about individual and team effort. He talked about the process, the belief that the right leadership combined with exceptional effort would inevitably deliver remarkable results.

- A Good Leader Is First a Teacher. John Wooden’s first job out of college was teaching high school English. And for the rest of his career, he always thought of himself as a teacher. Wooden taught through four components: demonstration, imitation, correction, and repetition. Coach Wooden had this absolutely right from my perspective: To be a great leader and executive, you almost always have to be a great teacher first.

- Teamwork Is a Necessity. Bill Walton, one of Coach Wooden’s most accomplished and greatest players, said it best: “Coach Wooden challenged us to believe that something special could come from the group effort. We live in a society that is constantly pushing us to be individual, to be selfish. But Coach Wooden constantly focused on the group, and how there could be no success unless everybody believed in the same goal and everybody came out of there feeling good about the success of others.”

- Failing to Prepare Is Preparing to Fail. This quote is often attributed to Coach Wooden, but it was first said by Benjamin Franklin. Coach Wooden was extraordinarily well-prepared. Even after years and years of amazing and unprecedented success, Coach Wooden still scripted each and every practice. He was famous for arriving to practice early to make sure everything was in order and that, in fact, he and the team were completely prepared to get the most out of that afternoon. Hospitals and health systems have “practices” as well: They are called “meetings.” What is the standard for preparation in your hospital organization? What is the quality of the work both before and after meetings? What is the level of preparation for consequential meetings such as rating agency presentations, Board approval of major initiatives, and important discussions with external parties? The longer my consulting and business career goes on, the more I have come to believe in and rely on impeccable preparation.

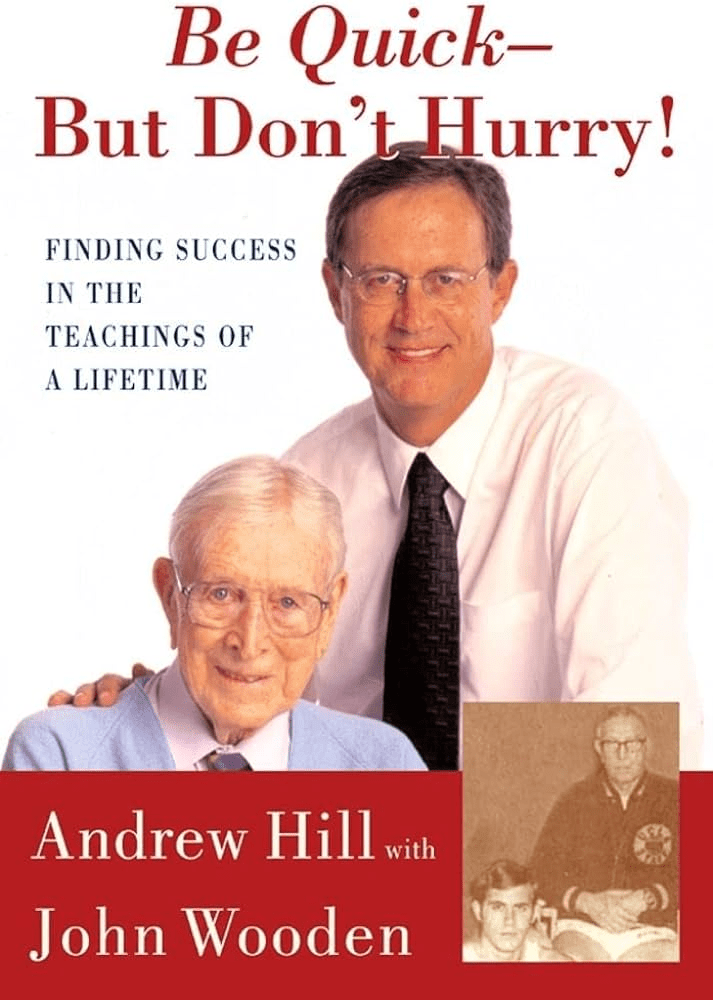

This blog covers just a few of Coach Wooden’s many approaches to and commentaries on management and leadership. But the above observations are a useful start. It is important to disclose that this blog post was guided by and drew quotes from an excellent book, Be Quick—But Don’t Hurry: Finding Success in the Teachings of a Lifetime, which was written by Andrew Hill (a former UCLA player) with the assistance of John Wooden. The book was published by Simon & Schuster in 2001 but as readers can easily see, the book by Messrs. Hill and Wooden remains absolutely relevant today. The book is a short read but will prove to be a good use of your time and your curiosity.

Learn and be smart. Those are the key attributes for today’s healthcare executives. Yesterday’s executive techniques are no longer getting the job done. Hospital leaders must be better in order to deal with the long list of obstacles that are preventing hospital success. Coach Wooden invented a unique roadmap to executive learning and leadership. That Wooden roadmap is definitely “old school,” but that roadmap and its attendant theories and methods are absolutely worth your attention.

Is our collaborative culture slowing down our ability to act quickly?

https://mailchi.mp/cd8b8b492027/the-weekly-gist-january-26-2024?e=d1e747d2d8

“We have a collaborative culture; it’s one of our system’s core values. But it takes us far too long to make decisions.” A health system CEO made this comment at a recent meeting, giving voice to a dilemma many system executives are no doubt facing. Of course, leaders want their teams to collaborate—in any important decision, we want to hear different voices, consider diverse points of view, and incorporate various areas of expertise.

On the other hand, collaboration takes time, which we don’t have right now. It also can add complexity, be the enemy of clear direction, and muddy accountability. This CEO went on to make an essential connection: “My concern is that this protracted decision making isn’t just a process problem, but that it’s showing up in our results.

Take performance improvement—we all quickly agreed we need to cut costs, but it’s taking far too long for us to act, and I fear we’ll have trouble holding the new line over time.” She further mused

“I wonder if this problem is, at least in part, due to how we make decisions. We don’t make them quickly enough, they aren’t clear enough, and we don’t have the most effective system of accountability.”

On one hand, traditional hospital culture is rightly grounded in the safety, hierarchy, and tradition of a do-no-harm world. But on the other hand, today’s economic, technological, and competitive environments require an approach to operations, revenue, and growth that has the aggressiveness of a Fortune 50 company. This should not be an either-or situation. Health systems can uphold a culture of safety while also fostering nontraditional values that will drive the organization assertively toward the future – all while committing to change.

The Emotional IQ of Leadership

I recently had dinner with my good friend and colleague, Dave Blom. For many years, Dave was the President and CEO of Ohio Health. During his tenure, Ohio Health was one of America’s most successful health systems by any measure. Dave Blom was known nationally as a calm, steady, and thoughtful hospital leader.

Dave and I were talking about the difficulties of leading and managing complex healthcare organizations in the post-Covid era. The hospital problems of finance, staffing, access, and inflation have been well itemized and documented. While the day-to-day operating problems are undeniably significant and persistent, Dave and I agreed that the hospital leadership issues that really matter right now center around the ability of hospital executives to possess and demonstrate an authentic emotional IQ to lead a diverse workforce in such difficult circumstances.

Such a realization is supported by the recognition that no matter how technically excellent they are, hospitals are just not like other organizations in other industries. Taking care of patients—in fact, taking care of communities—is not only managerially complicated but emotionally testing. Leadership gets much more complicated in the current environment.

Having moved the conversation to this point Dave and I then took on the definition of a workable and effective leadership emotional IQ. That emotional IQ is characterized by the following:

- Empathy. During Covid, when leadership was challenged at every level and at every American organization, the value of personal empathy moved to the forefront. Empathy is defined as “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” More directly, a hospital CEO needs to understand and share the feelings of his or her entire organization. Great hospital leaders understand the difference between sympathy and empathy. Sympathy is a passive emotion, an emotion that notes and cares about a problem but doesn’t necessarily act on that problem. Empathy is an active emotion. A leader with empathy not only notes the problem but immediately moves to be of help either at the personal or organizational level, whichever is required.

- Vulnerability. Vulnerability is defined as “the willingness to show emotion or to allow one’s weakness to be seen or known.” Historically, executive leadership—especially in corporate situations—has been trained and encouraged not to show emotion or weakness. But organizations are changing, and the composition of the hospital workforce is different. The patient care process is emotional in and of itself and the daily operational interaction demands a different kind of leadership—a leadership that is comfortable with both emotion and weakness.

- Humility. Executives who show humility “are willing to ask for help and don’t insist on everything done their way; they are quick to forgive and are known for their patience.” Humility also reflects changing organizational ecosystems. Humility is not generally indicative or compatible with the “military command” model of leadership. It is more supportive of a collaborative and cooperative leadership model, which has at its core a heavy dose of decentralization and delegation.

As our dinner was coming to a close, we took note of two other leadership observations.

First, when you create a leadership team that fully embraces the principles of empathy, vulnerability, and humility, then that emotional IQ combination creates the highest order goal of organizational trust. All of this is exceptionally meaningful since organizational trust is more important than ever, given that it is in such short supply at all levels of American society. Dave Blom then advanced the discussion to one further point. When you gain the full value of empathy, vulnerability, and humility and you add to that the organizational trust you have established, all the principled prerequisites for establishing corporate and managerial integrity are in place. Empathy plus vulnerability plus humility equals organizational trust. And then empathy plus vulnerability plus humility plus trust equals organizational integrity.

The emotional IQ of leadership is not created by accident. It requires a hyper-aware organization at both the management and Board level. It requires governance and executive leaders who understand that hospital success cannot be achieved by technical and clinical excellence alone. That success must be built on a platform of an emotional IQ that is supported, valued, and shared by the entire hospital community.

10 signs your board has a strong pulse

Great systems are usually governed by great boards, who are made up of people who match the following 10 descriptions.

Great board members do more than comply with corporate governance structure and rules. Too often, board members have loose ties to one another, are passive to the wants and views of the CEO or are not as informed about the specifics of healthcare as they ought to be. We view all of these traits, and more, as signs that a board has lost its charge and is no longer effectively governing.

We consider the following 10 items as descriptors of a board member who has a strong pulse and adds value to a governing body.

1. The board member is active, engaged and passionate about being a board member. No board can afford to have disengaged members. Bylaws and attendance requirements are important, but simply complying with them does not necessarily equate to being an active, contributing and passionate trustee. Engaged board members show up to meetings, and they show up prepared. While members typically refrain from meddling in day-to-day operations, boards with high levels of trust and candor make a point to communicate with the CEO outside of scheduled board meetings. Quality of board engagement is an important contributing factor to board performance, and there is a correlation between board engagement and the ability to attract board members. Everything that follows is dependent on board engagement.

2. The board member has a point of view on what the organization must be great at, and the board member is vehement about it. Health systems cannot be all things to all people, although the opportunities to attempt this are ample. The best organizations are not static, but disciplined. Well-governed systems know the specialties they are great in, and they continue to double down on their strengths. Their boards are cognizant of where revenues come from and ensure resources are allocated accordingly.

3. The board member realizes that her top job is to ensure the system has great leadership in place. Leaders can fall short in all sorts of ways, some more visible and easily detectable than others. The active, engaged and vehement board does not easily accept disappointment. Boards have many steps at their disposal to manage a problem before firing a CEO or senior leader, but they should never function in a way where termination is unthinkable. Boards cause great damage when they tolerate mediocre performance or compromised values among people at the top of the organization.

4. The board member understands accountability for patient safety and quality of care rests firmly in the boardroom. It rests on board members to insist that they receive sufficient, timely information about patient safety and care quality from the CEO. It rests on board leadership to ensure members have access to expertise and resources to properly obtain, process and interpret this information. It is not a bad idea for quality expertise to be included in board members’ competency profiles and for boards to undergo training and continued education in quality and safety. This is especially relevant for board members who come from industries outside of healthcare. It rests on the board when care quality declines or when lapses in patient safety are unaddressed: It is unacceptable for a board to say it missed the memo on care outcomes or that it did not understand the information in front of it.

5. The board member is a watchdog on societal, governance and audit issues. Informed citizens make for strong board members. It is important to not only be plugged in and aware of the issues and challenges confronting the organization today, but to be aware of broader societal issues that could affect system strategy and performance tomorrow. This is not hypothetical thinking. The past year was a master class in how broader issues affected healthcare in acute and direct ways: systemic racism, a global supply chain and a churning labor market are just three. Good boards are made up of members who stay informed and are biased toward anticipatory thinking, in which they are eager to explore the ways in which issues larger than or outside of their industry may come to affect the organization they help govern.

6. The board member supports the leadership team, but also questions it and holds it accountable. Board members cannot be pushovers for leadership. Directors are nominated by existing board directors on the nominating committee, which often includes the CEO. As a result, trustees can empathize with the CEO of the organization on whose board they sit. Empathy does not equate to blind acceptance, but this is nonetheless a dynamic trustees should be aware of and work to keep in check. It is not unusual for board members to struggle when giving candid feedback to the CEO, for example. As a result, chief executives carry on and live in a bigger and bigger bubble.

It’s worth noting that the reverse can occur within boardrooms as well, in which board members disagree about strategy and seek a CEO they can easily influence. At the end of the day, being a pushover is not associated with strong leadership and should be avoided by both trustees and senior executives. Instead, trustees need to embrace constructive tension in the boardroom. Questions, challenges and disagreements that reach resolution can drive valuable dialogue and stronger outcomes.

7. The board member allows others to voice their thoughts. In many boardrooms, a small number of the participants do most of the talking while the majority stays relatively quiet. A powerful or well-connected member may dominate discussions. Ideally, boards embrace the middle in interpersonal communication, with trustees contributing not too much nor too little. Either goes against the board’s very reason for being.

8. The board member helps ensure the board as a whole reflects the racial, ethnic, gender, religious and socioeconomic diversity of the community served by the organization. This is important for a number of reasons, with health equity being principal. Trustees are stewards for the communities they serve. For hospitals and health systems to increase opportunities for everyone to be healthier — including those who face the greatest obstacles — they need visions, strategies and goals that begin at the top from individuals who have viewpoints from the community. Without these insights, the board simply can’t govern effectively. Additionally, research has consistently found that teams of people who have diversity in knowledge and perspectives — as well as in age, gender and race — can be more creative and better avoid groupthink.

9. The board member is accessible. Just as no board wants its CEO in a bubble, governing bodies must actively resist this risk. For a stretch of time, boards were less visible groups of people who would meet four to six times a year in a mahogany-paneled room to decide the future of an organization that employs tens of thousands and serves even more. This dynamic cannot hold in healthcare. Community members and employees should know — or be able to easily learn — who serves on their health system’s board. If stakeholders bring issues or concerns to a board member, the trustee should be prepared to respond and follow up. In 2021’s healthcare, board members cannot breathe rarified air.

10. The board member emulates the values of the health system. So often when people talk about the tone being set at the top, they have the CEO in mind. The board is just as responsible, if not more responsible, for this charge. What a board permits, it promotes. Board members that emulate system values are better positioned to collaborate with mutual respect, candor and trust. Board members whose values are mismatched or personal agendas are at cross-purposes with the good of the organization should be replaced.