The Affordable Care Act turned 14 on March 23. It has done a lot of good for a lot of people, but big changes in the law are urgently needed to address some very big misses and consequences I don’t believe most proponents of the law intended or expected.

At the top of the list of needed reforms: restraining the power and influence of the rapidly growing corporations that are siphoning more and more money from federal and state governments – and our personal bank accounts – to enrich their executives and shareholders.

I was among many advocates who supported the ACA’s passage, despite the law’s ultimate shortcomings. It broadened access to health insurance, both through government subsidies to help people pay their premiums and by banning prevalent industry practices that had made it impossible for millions of American families to buy coverage at any price. It’s important to remember that before the ACA, insurers routinely refused to sell policies to a third or more applicants because of a long list of “preexisting conditions” – from acne and heart disease to simply being overweight – and frequently rescinded coverage when policyholders were diagnosed with cancer and other diseases.

While insurance company executives were publicly critical of the law, they quickly took advantage of loopholes (many of which their lobbyists created) that would allow them to reap windfall profits in the years ahead – and they have, as you’ll see below.

Among other things, the ACA made it unlawful for most of us to remain uninsured (although Congress later repealed the penalty for doing so). But, notably, it did not create a “public option” to compete with private insurers, which many advocates and public policy experts contended would be essential to rein in the cost of health insurance. Many other reform advocates insisted – and still do – that improving and expanding the traditional Medicare program to cover all Americans would be more cost-effective and fair.

I wrote and spoke frequently as an industry whistleblower about what I thought Congress should know and do, perhaps most memorably in an interview with Bill Moyers. During my Congressional testimony in the months leading up to the final passage of the bill in 2010, I told lawmakers that if they passed it without a public option and acquiesced to industry demands, they might as well call it “The Health Insurance Industry Profit Protection and Enhancement Act.”

A health plan similar to Medicare that could have been a more affordable option for many of us almost happened, but at the last minute, the Senate was forced to strip the public option out of the bill at the insistence of Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Connecticut), who died on March 27, 2024. The Senate did not have a single vote to spare as the final debate on the bill was approaching, and insurance industry lobbyists knew they could kill the public option if they could get just one of the bill’s supporters to oppose it. So they turned to Lieberman, a former Democrat who was Vice President Al Gore’s running mate in 2000 and who continued to caucus with Democrats. It worked. Lieberman wouldn’t even allow a vote on the bill if it created a public option. Among Lieberman’s constituents and campaign funders were insurance company executives who lived in or around Hartford, the insurance capital of the world. Lieberman would go on to be the founding chair of a political group called No Labels, which is trying to find someone to run as a third-party presidential candidate this year.

The work of Big Insurance and its army of lobbyists paid off as insurers had hoped. The demise of the public option was a driving force behind the record profits – and CEO pay – that we see in the industry today.

The good effects of the ACA:

Nearly 49 million U.S. residents (or 16%) were uninsured in 2010. The law has helped bring that down to 25.4 million, or 8.3% (although a large and growing number of Americans are now “functionally uninsured” because of unaffordable out-of-pocket requirements, which President Biden pledged to address in his recent State of the Union speech).

The ACA also made it illegal for insurers to refuse to sell coverage to people with preexisting conditions, which even included birth defects, or charge anyone more for their coverage based on their health status; it expanded Medicaid (in all but 10 states that still refuse to cover more low-income individuals and families); it allowed young people to stay on their families’ policies until they turn 26; and it required insurers to spend at least 80% of our premiums on the health care goods and services our doctors say we need (a well-intended provision of the law that insurers have figured out how to game).

The not-so-good effects of the ACA:

As taxpayers and health care consumers, we have paid a high price in many ways as health insurance companies have transformed themselves into massive money-making machines with tentacles reaching deep into health care delivery and taxpayers’ pockets.

To make policies affordable in the individual market, for example, the government agreed to subsidize premiums for the vast majority of people seeking coverage there, meaning billions of new dollars started flowing to private insurance companies. (It also allowed insurers to charge older Americans three times as much as they charge younger people for the same coverage.) Even more tax dollars have been sent to insurers as part of the Medicaid expansion. That’s because private insurers over the years have persuaded most states to turn their Medicaid programs over to them to administer.

Insurers have bulked up incredibly quickly since the ACA was enacted through consolidation, vertical integration, and aggressive expansion into publicly financed programs – Medicare and Medicaid in particular – and the pharmacy benefit space. Premiums and out-of-pocket requirements, meanwhile, have soared.

We invite you to take a look at how the ascendency of health insurers over the past several years has made a few shareholders and executives much richer while the rest of us struggle despite – and in some cases because of – the Affordable Care Act.

BY THE NUMBERS

In 2010, we as a nation spent $2.6 trillion on health care. This year we will spend almost twice as much – an estimated $4.9 trillion, much of it out of our own pockets even with insurance.

In 2010, the average cost of a family health insurance policy through an employer was $13,710. Last year, the average was nearly $24,000, a 75% increase.

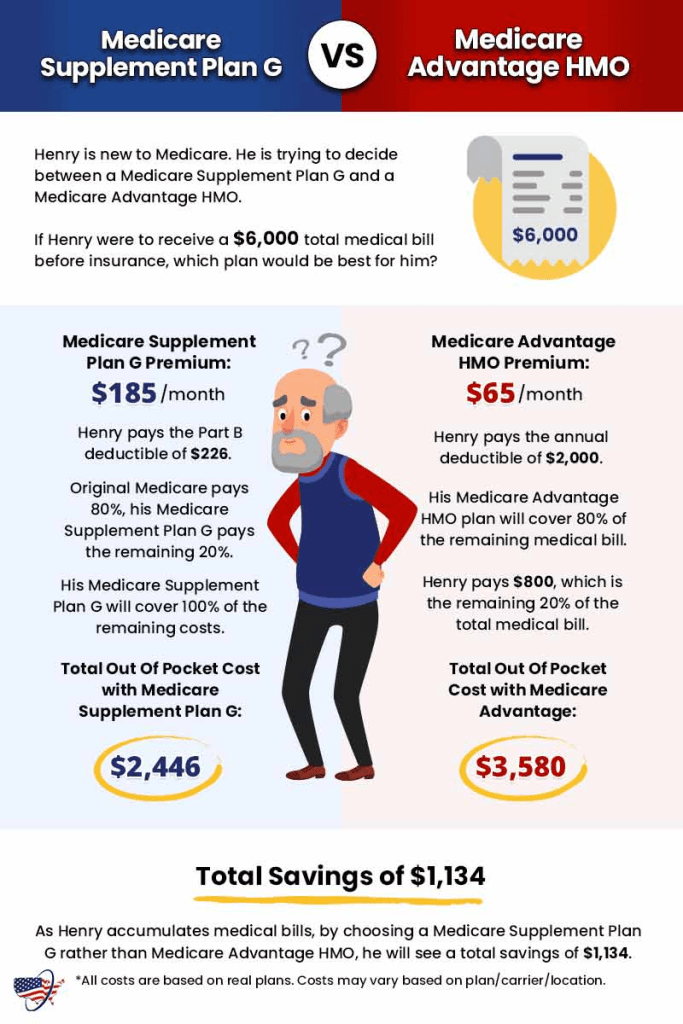

The ACA, to its credit, set an annual maximum on how much those of us with insurance have to pay before our coverage kicks in, but, at the insurance industry’s insistence, it goes up every year. When that limit went into effect in 2014, it was $12,700 for a family. This year, it has increased by 48%, to $18,900. That means insurers can get away with paying fewer claims than they once did, and many families have to empty their bank accounts when a family member gets sick or injured. Most people don’t reach that limit, but even a few hundred dollars is more than many families have on hand to cover deductibles and other out-of-pocket requirements. Now 100 million Americans – nearly one of every three of us – are mired in medical debt, even though almost 92% of us are presumably “covered.” The coverage just isn’t as adequate as it used to be or needs to be.

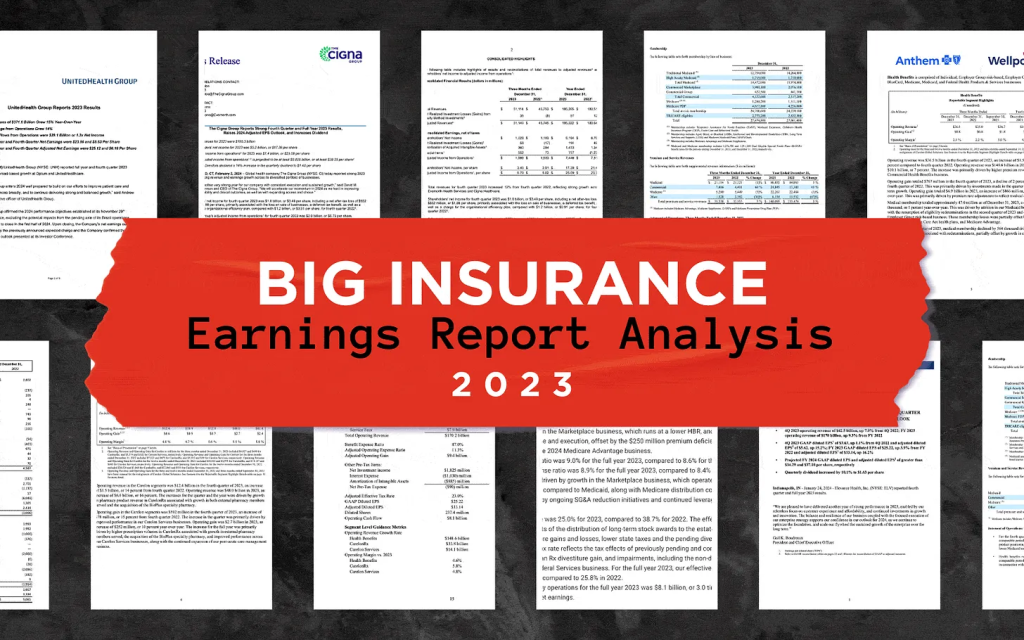

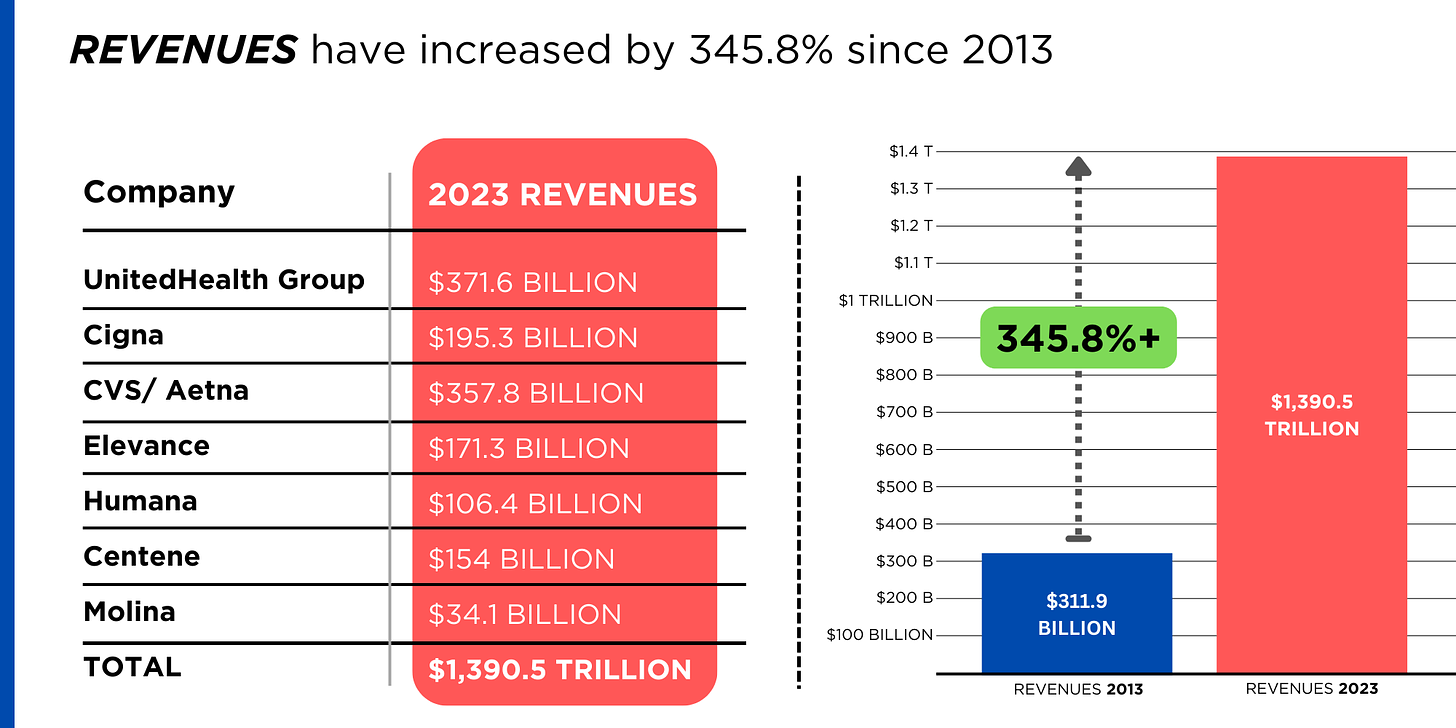

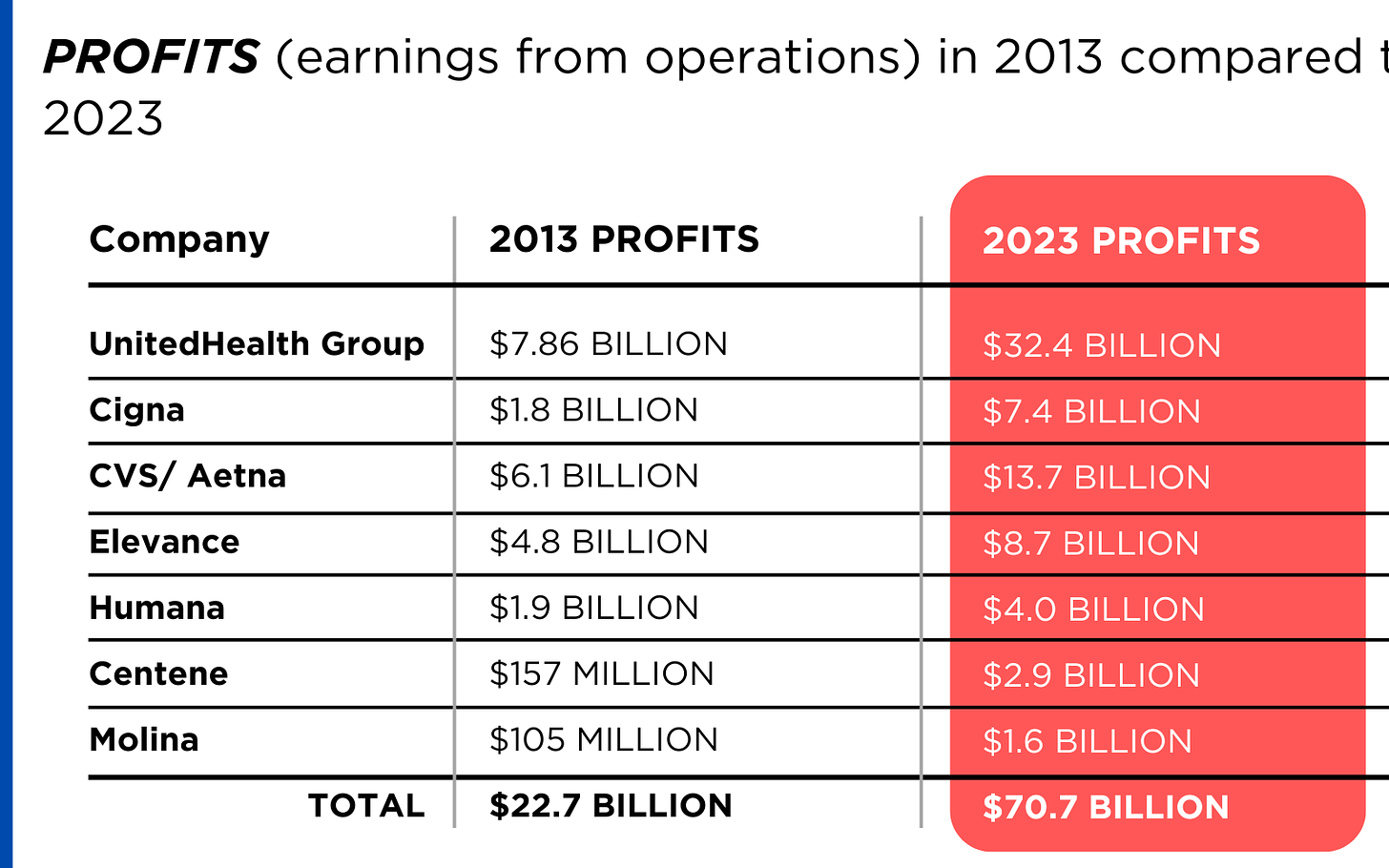

Meanwhile, insurance companies had a gangbuster 2023. The seven big for-profit U.S. health insurers’ revenues reached $1.39 trillion, and profits totaled a whopping $70.7 billion last year.

SWEEPING CHANGE, CONSOLIDATION–AND HUGE PROFITS FOR INVESTORS

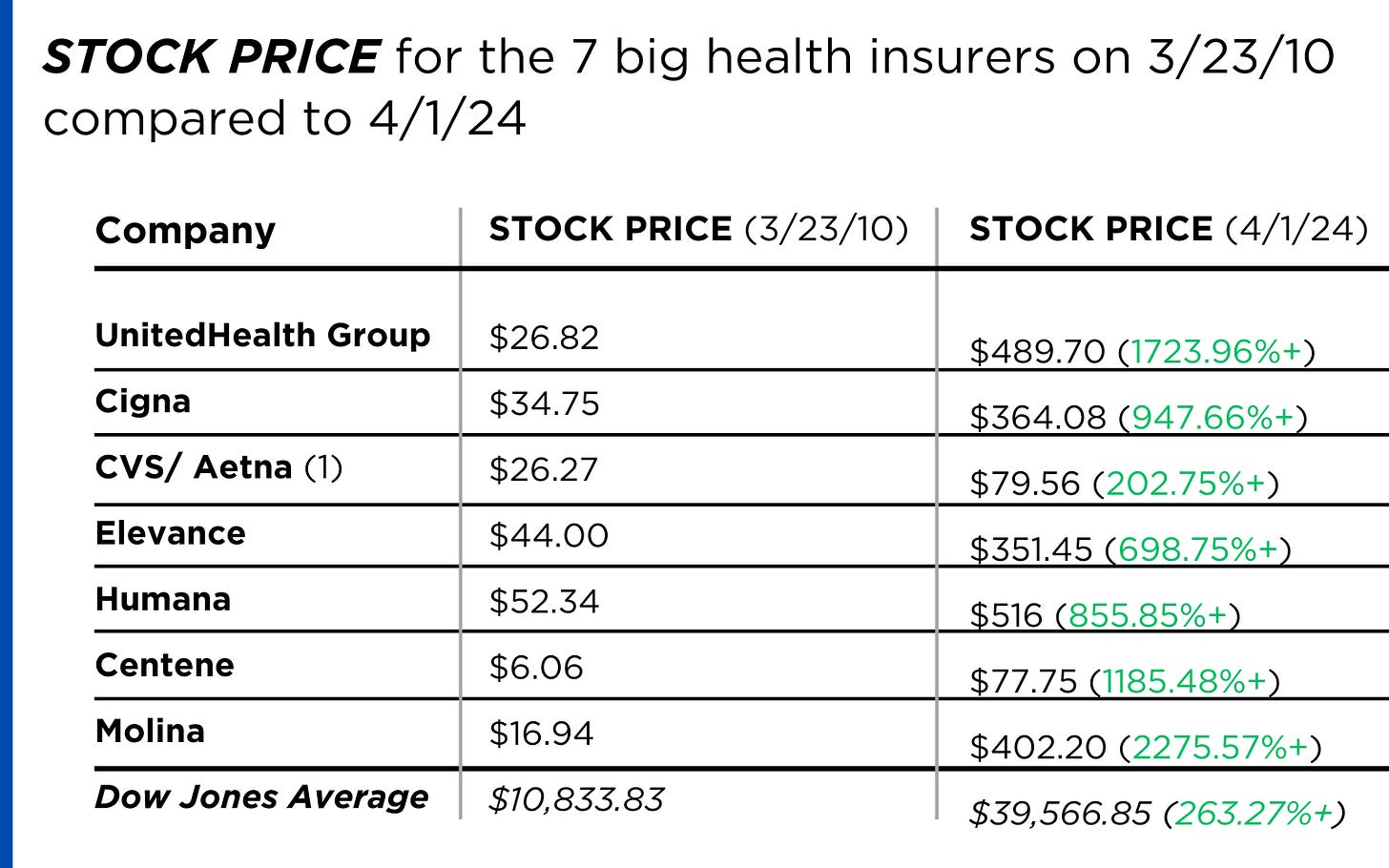

Insurance company shareholders and executives have become much wealthier as the stock prices of the seven big for-profit corporations that control the health insurance market have skyrocketed.

REVENUES collected by those seven companies have more than tripled (up 346%), increasing by more than $1 trillion in just the past ten years.

PROFITS (earnings from operations) have more than doubled (up 211%), increasing by more than $48 billion.

The CEOs of these companies are among the highest paid in the country. In 2022, the most recent year the companies have reported executive compensation, they collectively made $136.5 million.

U.S. HEALTH PLAN ENROLLMENT

Enrollment in the companies’ health plans is a mix of “commercial” policies they sell to individuals and families and that they manage for “plan sponsors” – primarily employers and unions – and government/enrollee-financed plans (Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare for military personnel and their dependents and the Federal Employee Health Benefits program).

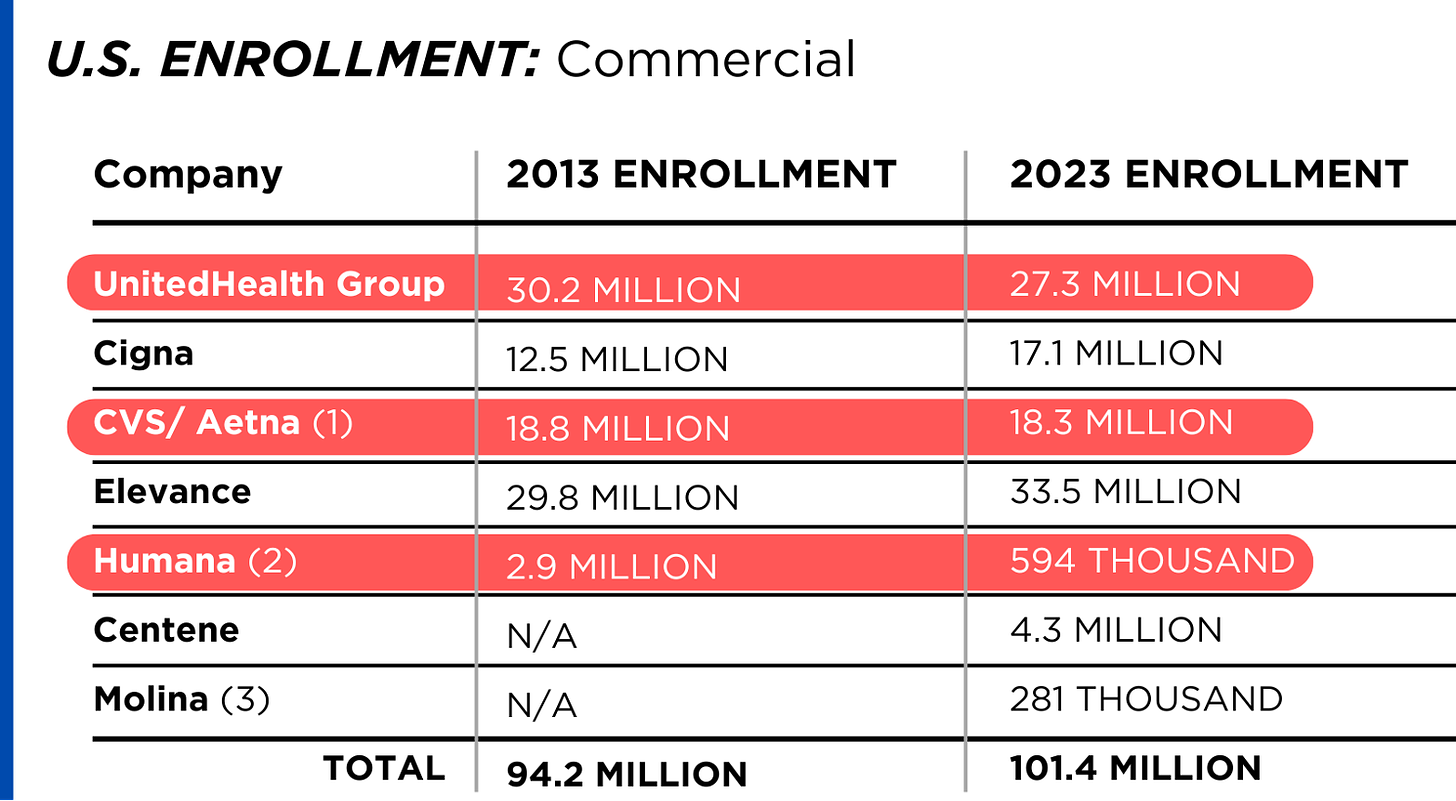

Enrollment in their commercial plans grew by just 7.65% over the 10 years and declined significantly at UnitedHealth, CVS/Aetna and Humana. Centene and Molina picked up commercial enrollees through their participation in several ACA (Obamacare) markets in which most enrollees qualify for federal premium subsidies paid directly to insurers.

While not growing substantially, commercial plans remain very profitable because insurers charge considerably more in premiums now than a decade ago.

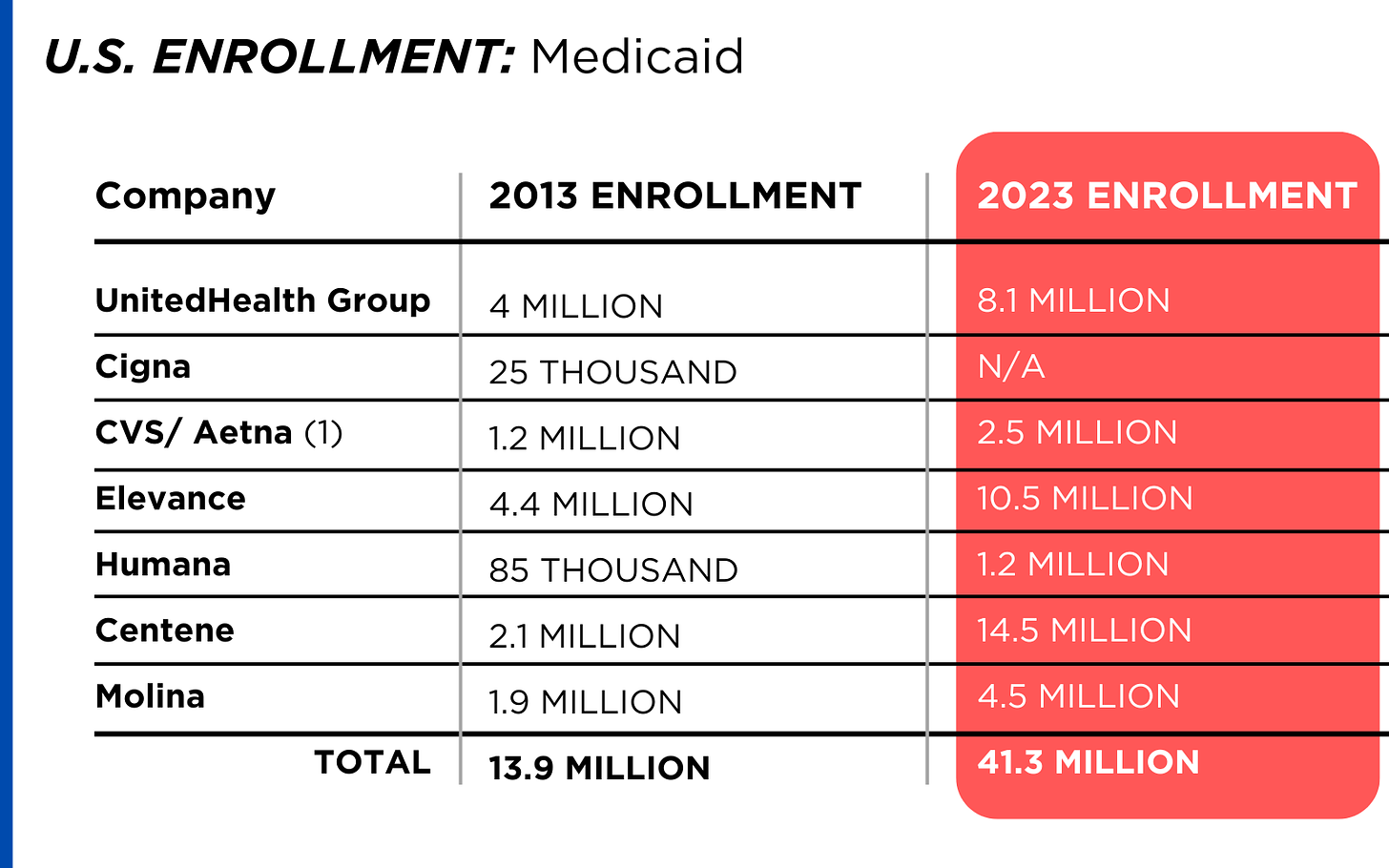

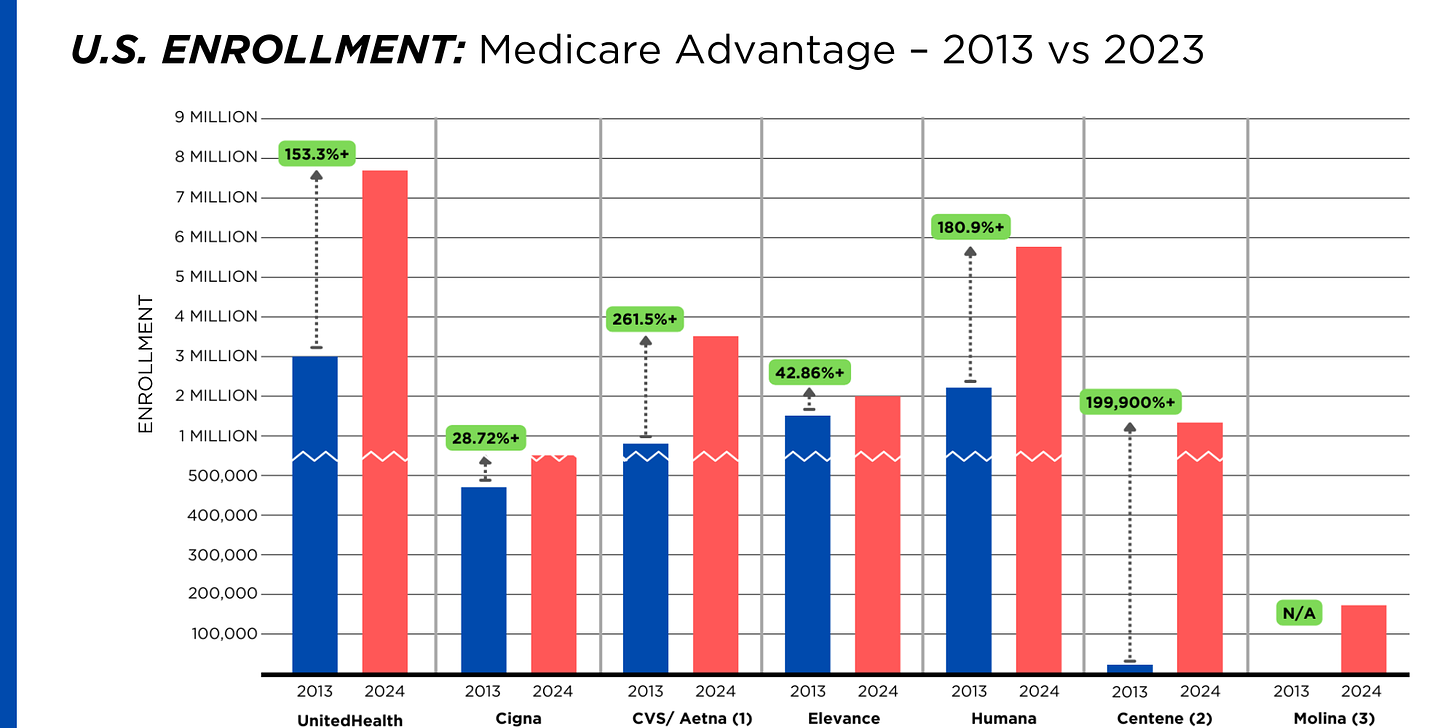

By contrast, enrollment in the government-financed Medicaid and Medicare Advantage programs has increased 197% and 167%, respectively, over the past 10 years.

Of the 65.9 million people eligible for Medicare at the beginning of 2024, 33 million, slightly more than half, enrolled in a private Medicare Advantage plan operated by either a nonprofit or for-profit health insurer, but, increasingly, three of the big for-profits grabbed most new enrollees.

Of the 1.7 million new Medicare Advantage enrollees this year, 86% were captured by UnitedHealth, Humana and Aetna.

Those three companies are the leaders in the Medicare Advantage business among the for-profit companies, and, according to the health care consulting firm Chartis, are taking over the program “at breakneck speed.”

It is worth noting that although four companies saw growth in their Medicare Supplement enrollment over the decade, enrollment in Medicare Supplement policies has been declining in more recent years as insurers have attracted more seniors and disabled people into their Medicare Advantage plans.

OTHER FEDERAL PROGRAMS

In addition to the above categories, Humana and Centene have significant enrollment in Tricare, the government-financed program for the military. Humana reported 6 million military enrollees in 2023, up from 3.1 million in 2013. Centene reported 2.8 million in 2023. It did not report any military enrollment in 2013.

Elevance reported having 1.6 million enrollees in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program in 2023, up from 1.5 million in 2013. That total is included in the commercial enrollment category above.

PBMs

As with Medicare Advantage, three of the big seven insurers control the lion’s share of the pharmacy benefit market (and two of them, UnitedHealth and CVS/Aetna, are also among the top three in signing up new Medicare Advantage enrollees, as noted above). CVS/Aetna’s Caremark, Cigna’s Express Scripts and UnitedHealth’s Optum Rx PBMs now control 80% of the market.

At Cigna, Express Scripts’ pharmacy operations now contribute more than 70% to the company’s total revenues. Caremark’s pharmacy operations contribute 33% to CVS/Aetna’s total revenues, and Optum Rx contributes 31% to UnitedHealth’s total revenues.

WHAT TO DO AND WHERE TO START

The official name of the ACA is the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The law did indeed implement many important patient protections, and it made coverage more affordable for many Americans.

But there is much more Congress and regulators must do to close the loopholes and dismantle the barriers erected by big insurers that enable them to pad their bottom lines and reward shareholders while making health care increasingly unaffordable and inaccessible for many of us.

Several bipartisan bills have been introduced in Congress to change how big insurers do business. They include curbing insurers’ use of prior authorization, which often leads to denials and delays of care; requiring PBMs to be more “transparent” in how they do business and banning practices many PBMs use to boost profits, including spread pricing, which contributes to windfall profits; and overhauling the Medicare Advantage program by instituting a broad array of consumer and patient protections and eliminating the massive overpayments to insurers.

And as noted above, President Biden has asked Congress to broaden the recently enacted $2,000-a-year cap on prescription drugs to apply to people with private insurance, not just Medicare beneficiaries. That one policy change could save an untold number of lives and help keep millions of families out of medical debt. (A coalition of more than 70 organizations and businesses, which I lead, supports that, although we’re also calling on Congress to reduce the current overall annual out-of-pocket maximum to no more than $5,000.)

I encourage you to tell your members of Congress and the Biden administration that you support these reforms as well as improving, strengthening and expanding traditional Medicare. You can be certain the insurance industry and its allies are trying to keep any reforms that might shrink profit margins from becoming law.