Growing in our leadership abilities, including growing in the knowledge of leadership and the relational aspect of leadership, should be a goal for every leader.

Sadly, in my experiencee, many leaders settle for a sort of status quo leadership rather than stretching themselves to continually improve. They settle for mediocre quality of leading, fathering than attempting the hard work of leadership excellence. They remain oblivious to the real health of their leadership and the organizations they lead. They may get by – people may say things are “okay” leaders, but no one would call them exceptional leaders.

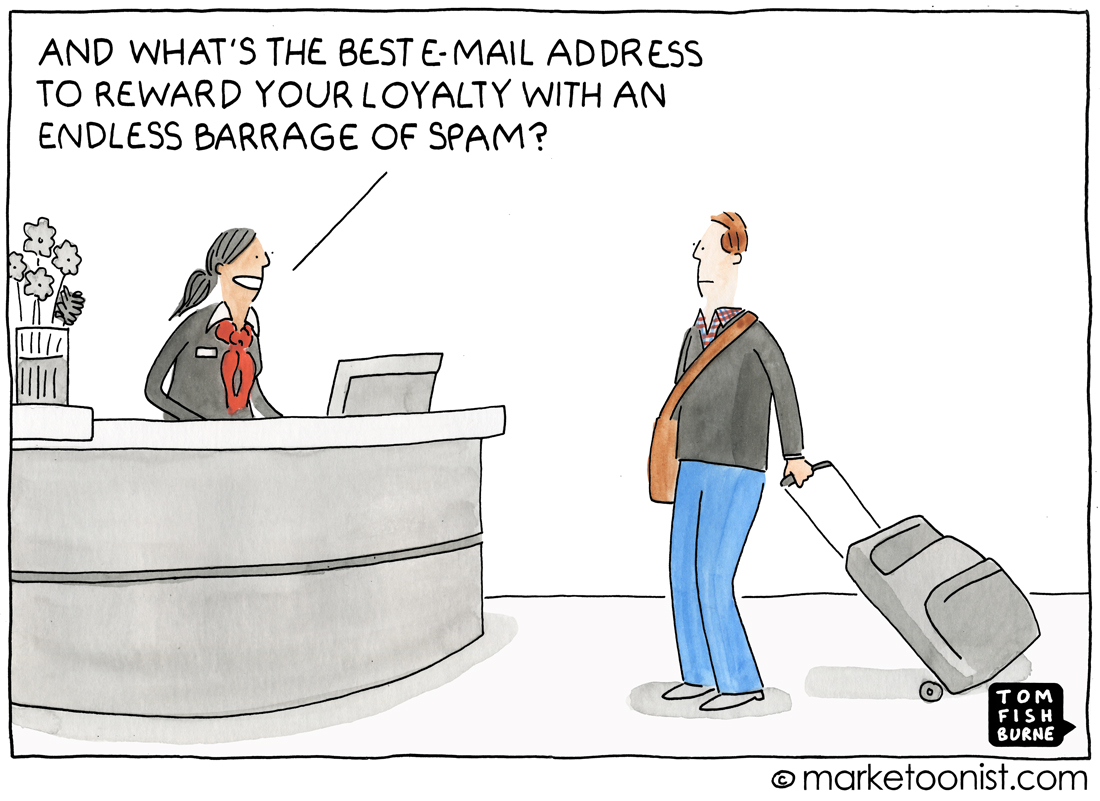

I have often referred to this style of leadership as shallow leadership.

Perhaps you’ve seen this before or maybe you’ve been guilty of providing shallow leadership. For seasons, at least, I am not too proud to admit I certainly have.

If you’re still wondering what shallow leadership looks like, let me offer some suggestions.

7 characteristics of shallow leadership:

Thinking your idea will be everyone’s idea. You assume everyone is on the same page with you. You think everyone thinks like you. That’s because you’ve stopped asking questions of your team. You have stopped evaluating everything. You aren’t open to constructive evaluation – of you.

Believing your way is the only way. You’re the leader- you must be right, right? Maybe you’ve had some success and it went to your head just a little. Perhaps you’ve become – or you’ve always been – a little stubborn or head strong. You may even be controlling. You have to make or sign off on every decision. You may never delegate. Those are all signs of shallow leadership, because you’ve likely shut out some of the best ideas within the organization – which reside among the people you are trying to lead.

Assuming you already know the answer. You think you’ve done it long enough to see it all, so you quit learning. You have stopped reading. You never meet with other leaders anymore.

Pretending to care when really you don’t. This is so common among shallow leaders. Shallow leaders have grown cold in their passion. They may speak the vision, but they’re just words on a page or hung on a wall now. They may even go through all the motions. They are still drawing a paycheck, but if the truth be known, they’d rather be anywhere than where they are right now.

Giving the response, which makes you most popular. Shallow leaders like to be liked. They never make the hard decisions, refuse to challenge, avoid conflict, and run from complainers. They ignore the real problems in the organization so things never really get better.

Refusing to make a decision. Often a shallow leader had a setback at some point. Things didn’t go as planned, so they’ve grown scared or overwhelmed and so they refuse to walk by faith. The team won’t move forward because the leader won’t move forward.

Ignoring the warning signs of poor health. This can be poor health in the organization, the team, or in the leader. Things may not be “awesome” anymore. Momentum may be suffering. Shallow leaders look the other way. And, again, it could be the leader. Your soul may be empty. You may be the one unhealthy. Or the team may be unhealthy. Shallow leaders refuse to see it or do anything about it.

We never achieve our best with shallow leadership. And, the first step is always to admit.