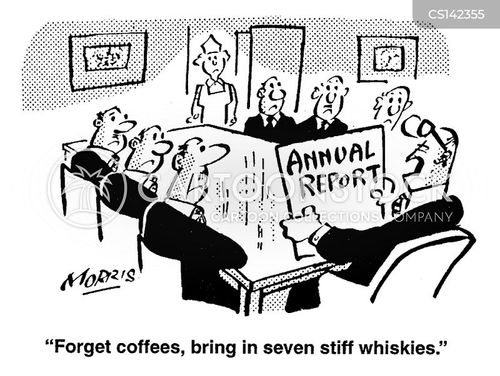

Cartoon – Moving Up from Senior to Aged Executive

Why the Theranos saga and Holmes’ trial is good for innovation

“Fake it until you make it” is an oft-repeated phrase among entrepreneurs promising to revolutionize, disrupt or transform. It can, however, have severe consequences for the healthcare sector when doctors and patients place their trust in the new or evolving venture. The criminal trial of Elizabeth Holmes, who faces a 20-year prison sentence, will help healthcare entrepreneurs see the legal ramifications of over-promising and under-delivering presumed medical advances.

This trial will generate headlines. More importantly, it will be a teachable moment for all of us trying to innovate our way through a deeply complicated and entrenched healthcare system – especially regarding patient-empowering technology. Holmes, and the company she founded, Theranos, marketed a means to disrupt traditional diagnostic business models where two large companies dominate a $54 billion market. The idea was to put patients in control of blood testing, using less amounts and creating a faster, lower-cost alternative. The business model envisioned consumers using Theranos equipment at retail locations including drug stores and supermarkets. As the marketing phrase goes, that was the “steak,” or substance to her pitch, but there was also “sizzle.”

The young, telegenic, and articulate Holmes became the widely-known public face of the company. Wearing black turtlenecks to draw comparisons to Steve Jobs and calling one of her blood-test devices “Edison” to align herself with the famous inventor, the media could not resist the story. That part worked: Theranos at one point was valued at $9 billion. Holmes declared her lab-test device was “the most important thing humanity ever built.” Much of the narrative she created about Theranos will now be used as evidence in her criminal trial just as it was in a separate Securities and Exchange civil fraud case in March.

Here is something we already know from the federal indictment handed down last month: prosecutors will cite Theranos press releases, media interviews, and promotional materials to support allegations that Holmes knowingly committed criminal fraud. In one example, the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Northern District of California cites a specific interview in which Holmes told a media outlet that Theranos could run “any combination of tests” from a single small blood sample. The indictment goes on to list public statements such as one on the company’s website that, “one tiny drop changes everything.”

In the Securities and Exchange Commission civil case, which Holmes settled, media interviews with the business press, which in turn were said to solicit investors, are likewise cited as evidence of financial fraud. The SEC’s civil complaint states that in 2013, “Holmes and Theranos began publicly touting Theranos’ proprietary analyzers in interviews with the media, notwithstanding Theranos’ use of commercially-available analyzers for patient testing.” Here too, several interviews with financial media outlets were used as examples including an e-mail exchange between Holmes and a reporter in which she tried to shape the story. As is widely known, the generally favorable media coverage that accelerated in 2013 abruptly ended.

Her company came under the scrutiny of The Wall Street Journal in 2015 when company whistleblowers went public raising questions about the underlying technology. This put Holmes and her company on the government’s radar. The narrative soon changed to actions intended to correct the company’s mistakes. Most notably, Theranos voided or corrected nearly a million blood-test results, calling into question untold numbers of health decisions made between doctors and patients.

Judges and juries take an especially harsh view of potentially harmful impacts on consumers. The FBI agent who investigated the case described charges of misleading consumers and doctors as endangering “health and lives.” Likely the most serious charge among the 11 counts Holmes faces is being unable to produce accurate and reliable results for numerous blood tests, including the detection of HIV, despite assertions to the contrary.

Yet Holmes is only the most recent and well-known among many healthcare practitioners who face charges or convictions of fraud. We can go back to the patent medicine movement in the early 1900’s, where a popular advertising slogan at the time was “a cure for what ails you.” In the late 1800’s there was actually a real-life snake oil salesman who traveled the country and gave demonstrations with live reptiles on how he made his product. Such antics with fake medicine led to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. So, a century later, why does this keep happening?

One recurring theme leading to healthcare fraud is what medical scholars have labeled “eminence-based” medicine. Simply put, this is an over-reliance on personality and stature from the individual believed to have authority on a particular medical subject. The term is a play on the words “evidence-based” medicine, where facts are supposed to be used to evaluate medical advances.

Some lessons are already being learned. Early stage and start-up blood-testing companies are emphasizing peer-reviewed data and clinical trials. One telling insight from an entrepreneur, as reported in Marketwatch, describes Theranos as a “big crater in the industry.” The founder of privately-held Athelas, a blood-testing firm, said Theranos, if executed correctly, “would make a massive impact in a really old, archaic industry.”

Faking it until you make it may work to a certain point and allow entrepreneurs a limited degree of latitude among investors as they develop technical approaches to support business models. As an entrepreneur myself, I am well aware of the need to convincingly show the promise of an invention – even before it is fully finished. However, it becomes financial fraud — potentially criminal activity — when you are not honest about the risk. Medical and consumer fraud, when patients are sucked into the hype and subsequently misled, becomes exponentially more serious. Neither is acceptable. The bottom line: Holmes’ trial will offer insight leading to less hype and more high-quality innovation.

The Trump administration is proposing huge changes in the way Medicare pays doctors for the most common of all medical services, the office visit, offering physicians basically the same amount, regardless of a patient’s condition or the complexity of the services provided.

Administration officials said the proposal would radically reduce paperwork burdens, freeing doctors to spend more time with patients. The government would pay one rate for new patients and another, lower rate for visits with established patients.

“Time spent on paperwork is time away from patients,” said Seema Verma, the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. She estimated that the change would save 51 hours of clinic time per doctor per year.

But critics say the proposal would underpay doctors who care for patients with the greatest medical needs and the most complicated ailments — and could discourage some physicians from taking Medicare patients. They also say it would increase the risk of erroneous and fraudulent payments because doctors would submit less information to document the services provided.

Medicare would pay the same amount for evaluating a patient with sniffles and a head cold and a patient with complicated Stage 4 metastatic breast cancer, said Ted Okon, the executive director of the Community Oncology Alliance, an advocacy group for cancer doctors and patients. He called that “simply crazy.”

Dr. Angus B. Worthing, a rheumatologist, said he understood the administration’s objective. “Doctors did not go to medical school to type on a computer all day,” he said.

But, he added: “This proposal is setting up a potential disaster. Doctors will be less likely to see Medicare patients and to go into our specialty. Patients with arthritis and osteoporosis may have to wait longer to see the right specialists.”

Private insurers often follow Medicare’s lead, so the proposed change has implications that go far beyond the Medicare program.

The proposal, part of Medicare’s physician fee schedule for 2019, is to be published Friday in the Federal Register, with an opportunity for public comment until Sept. 10. The new policies would apply to services provided to Medicare patients starting in January.

“We anticipate this to be a very, very significant and massive change, a welcome relief for providers across the nation,” Ms. Verma said, adding that it fulfills President Trump’s promise to “cut the red tape of regulation.”

“Evaluation and management services” are the foundation of an office visit. Medicare now recognizes five levels of office visits, with Level 5 involving the most comprehensive medical history and physical examination of a patient, and the most complex decision making by the doctor.

Level 1 is mostly for nonphysician services: for example, a five-minute visit with a nurse to check the blood pressure of a patient recently placed on a new medication.

A Level 5 visit could include a thorough hourlong evaluation of a patient with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, high blood pressure and diabetes with blood sugar out of control.

“The differences between Levels 2 to 5 are often really difficult to discern and time-consuming to document,” said Dr. Kate Goodrich, Medicare’s chief medical officer.

Medicare payment rates for new patients now range from $76 for a Level 2 office visit to $211 for a Level 5 visit. The Trump administration proposal would establish a single new rate of about $135. That could mean gains for doctors who specialize in routine care, but a huge hit for those who deal mainly with complicated patients, such as rheumatologists and oncologists.

For established patients, the proposal calls for a payment rate of about $93, in place of current rates ranging from $45 to $148 for the four different levels of office visits.

“This proposal is likely to penalize physicians who treat sicker patients, even though they spend more time and effort and more resources managing those patients,” said Deborah J. Grider, who has audited tens of thousands of medical records and written a book on the subject.

Dr. Atul Grover, the executive vice president of the Association of American Medical Colleges, said, “The single payment rate may not reflect the resources needed to treat patients we see at academic medical centers — the most vulnerable patients, those who have complex medical needs.”

While the proposal would redistribute money among doctors, it is not intended to cut spending under Medicare’s physician fee schedule, which totals roughly $70 billion a year.

If the new rules really do simplify their work, doctors say, they will be elated.

“We can focus more on patient care and less on the administrative burden of documentation and billing,” said Dr. David B. Glasser, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “We sometimes joke that it can be more complicated trying to get the coding level right than it is to figure out what’s wrong with the patient.”

But, Dr. Glasser said, the financial impact of the proposal on eye doctors is not yet clear.

Documentation requirements have increased in response to growing concerns about health care fraud and improper payments that cost Medicare billions of dollars a year.

In many cases, federal auditors could not determine whether services were actually provided or were medically necessary. In some cases, they found that doctors had billed Medicare — and patients — for more costly services than they actually performed.

In a report required by federal law, officials estimated early this year that 18 percent of Medicare payments for office visits with new patients were incorrect or improper, about three times the error rate for established patients.

To prevent fraud and abuse, Medicare officials have repeatedly told doctors to document their claims. “If it is not documented, it has not been done” — that is the principle set forth in Medicare’s billing manual for doctors.

The Trump administration is moving away from that policy.

“We have proposed to move to a system with minimal documentation requirements for Levels 2 to 5 and one single payment rate,” Dr. Goodrich said.

Doctors now must provide more documentation for higher levels of care. Under the proposal, “practitioners would only need to meet documentation requirements currently associated with a Level 2 visit.” That would reduce the need for audits to verify the level of office visits.

Medicare officials acknowledged that doctors who typically bill at Levels 4 and 5 could see financial losses under the proposal. But they said some of the losses could potentially be offset by “add-on payments” for primary care doctors and certain other medical specialists.

With such adjustments, Medicare officials said, the impact on most doctors would be relatively modest. A table included in the proposed rule indicates that obstetricians and gynecologists would gain the most, while dermatologists, rheumatologists and podiatrists would lose the most.

LifePoint Health owns hospitals in mostly rural areas.

For-profit hospital system LifePoint Health is nearing a deal to sell itself to private equity firm Apollo Global Management for $6 billion, including debt, Reuters reports. Apollo acquired a separate hospital chain — RegionalCare Hospital Partners, which is now known as RCCH HealthCare Partners — in 2015.

Why it matters: Private equity is craving health care deals right now, and this buyout would further consolidate the hospital industry, which is attempting to turn around a pattern of stagnant admissions.

Reuters reported Friday that private equity firm Apollo Global Management was considering buying LifePoint Health in a deal valued at $6 billion, which included debt. Axios’ Bob Herman breaks down the proposed deal…

Thought bubble, per Bob: Private equity has its hands all over the health care industry these days. But it’s a little surprising to hear such a large price tag for a company that owns mostly rural hospitals, which have struggled with fewer admissions and have relied more on the lower-paying Medicare and Medicaid programs.

The bottom line: Gary Taylor, an analyst with J.P. Morgan Securities, wrote this to hospital investors over the weekend, “We certainly do not expect another superior offer for a low-growth, challenged rural hospital company.”

A public health care plan — once deemed too liberal to make it into the Affordable Care Act — is now the more moderate position for many Democrats who are uncomfortable with the party’s rapid embrace of “Medicare for All.”

Yes, but: Democrats haven’t decided yet what a public option should look like.