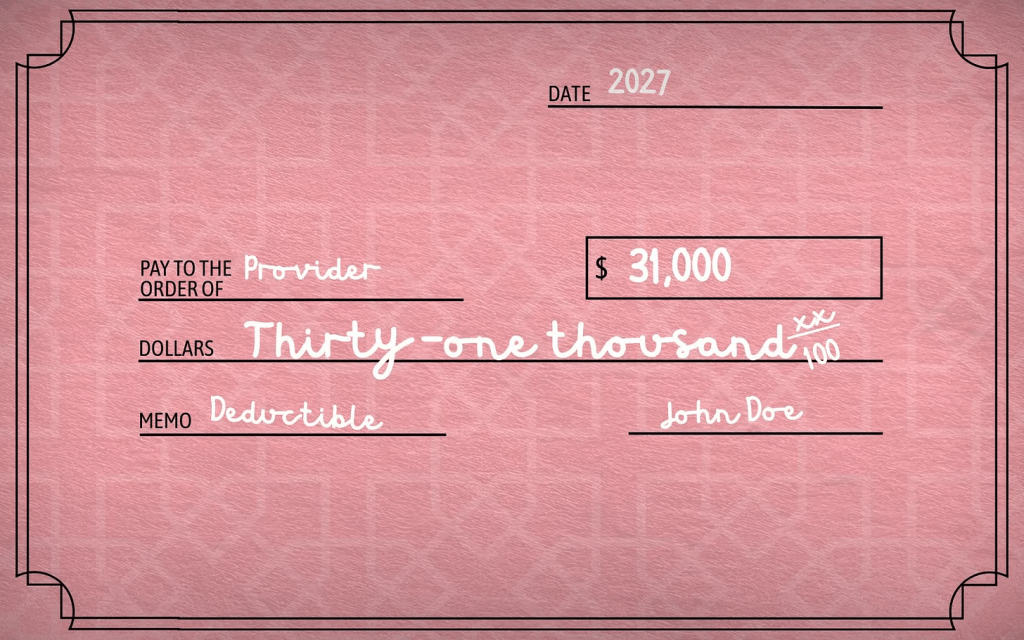

Trump’s proposal would revive “catastrophic” plans with deductibles as high as $31,000 — shifting even more costs onto patients with cancer, chronic illness, and medical emergencies.

On Friday, Erica Bersin – who has two chronic illnesses, including multiple sclerosis – wrote about the challenges of finding a decent and affordable health plan in the ACA marketplace. As a sole proprietor, the only plan with a manageable premium ($330 a month) came with a $10,000 deductible. MS drugs are expensive and many people with the disease have to pay hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars out of their own pockets before their coverage kicks in. Sadly, the way the ACA plans are structured, Americans with chronic conditions – and others who are diagnosed with cancer or have a heart attack or other acute medical event and have no option for coverage other than the ACA marketplace – are penalized financially far more than the rest of us..

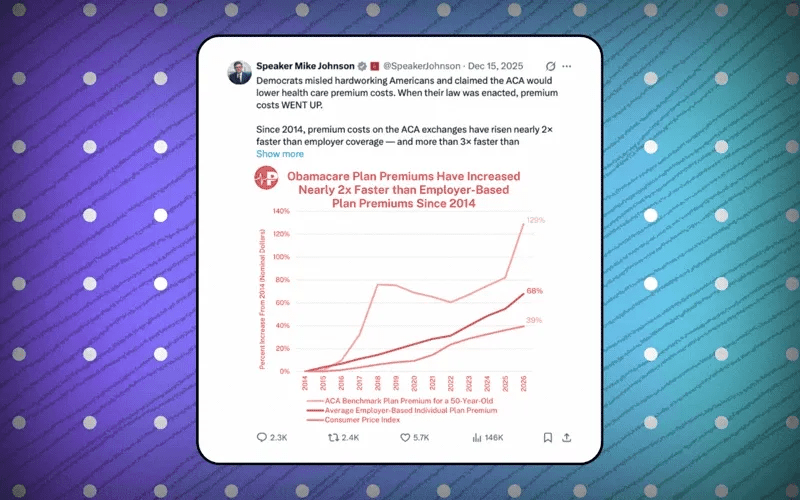

But instead of helping those folks out, the Trump administration is proposing to change the marketplace in ways that will make a $10,000 deductible seem like a bargain. Say hello to a $31,000 family deductible. And even if you’re covered by an employer-sponsored plan and in no imminent danger of being enrolled in a plan like that, know that their reappearance (they were outlawed 16 years ago), will push your premiums even higher than they already are. That’s because hospitals and physician practices know people enrolled in those plans will not be able to pay their bills. They’ll have no option but to increase their prices to cover the additional bad debt.

Health insurance policies with deductibles that high were prevalent before the Affordable Care Act was enacted in 2010. When I was a health insurance executive, I knew some insurers were selling policies with family deductibles north of $50,000. Not only that, many of them had annual and lifetime caps and wouldn’t pay for any care related to a preexisting condition.

They were officially called “catastrophic” plans. Patient and consumer advocates had a more appropriate name for them: junk plans. They were outlawed by the ACA, and I thought they had been buried for good. Unfortunately, the Trump administration is bringing them back to life.

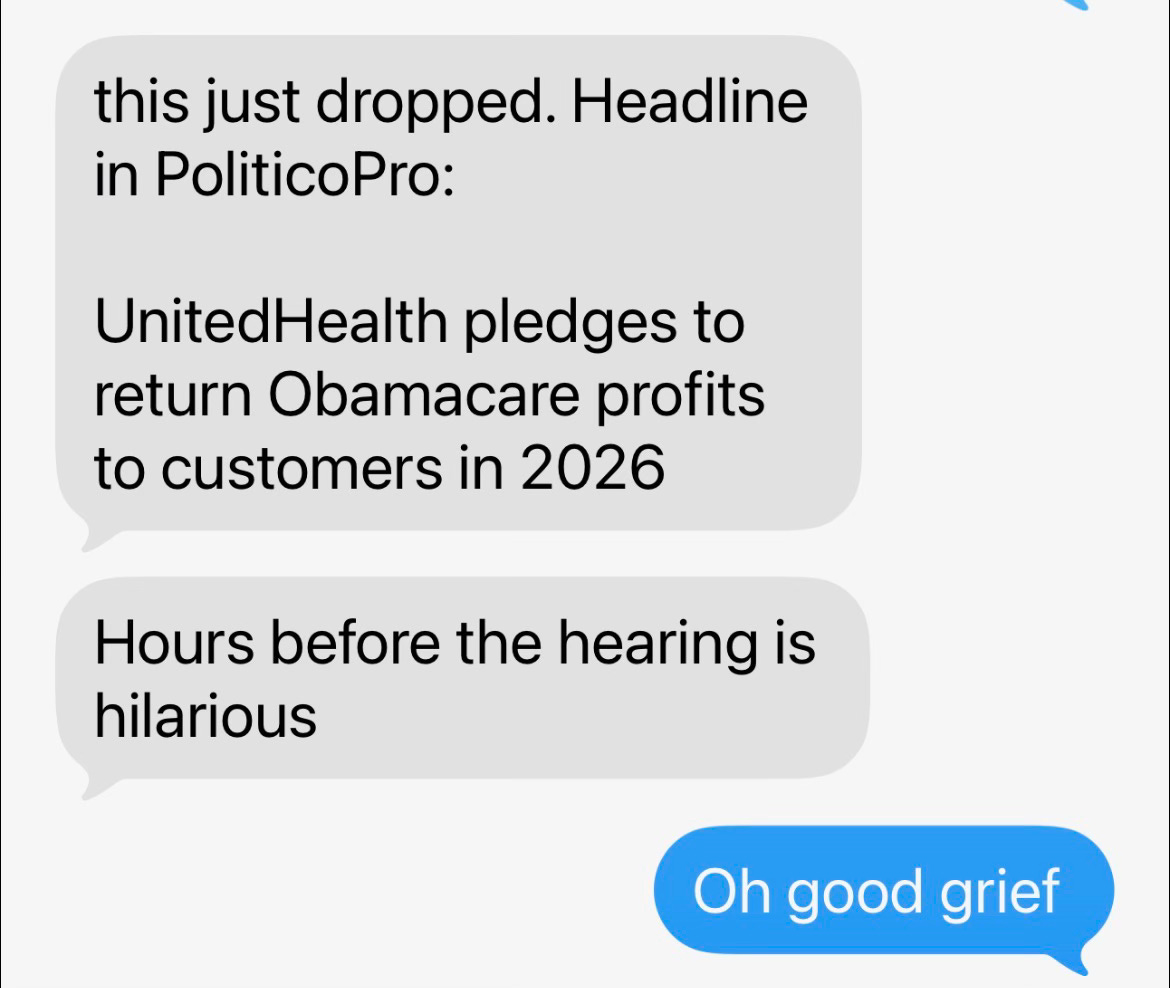

I’m sure my former colleagues in the health insurance business went to work immediately getting those plans ready to sell once again to unsuspecting customers. That’s because they can be very, very profitable. Imagine having to pay $50,000 – or even $31,000 – out of your own pocket every year before your insurer will cover the care your doctor says you need. Cigna, where I worked, as well as Aetna and UnitedHealthcare, the country’s biggest health insurers, sold plans like that and collected billions in premiums every month but paid little if anything out in claims during a given year.

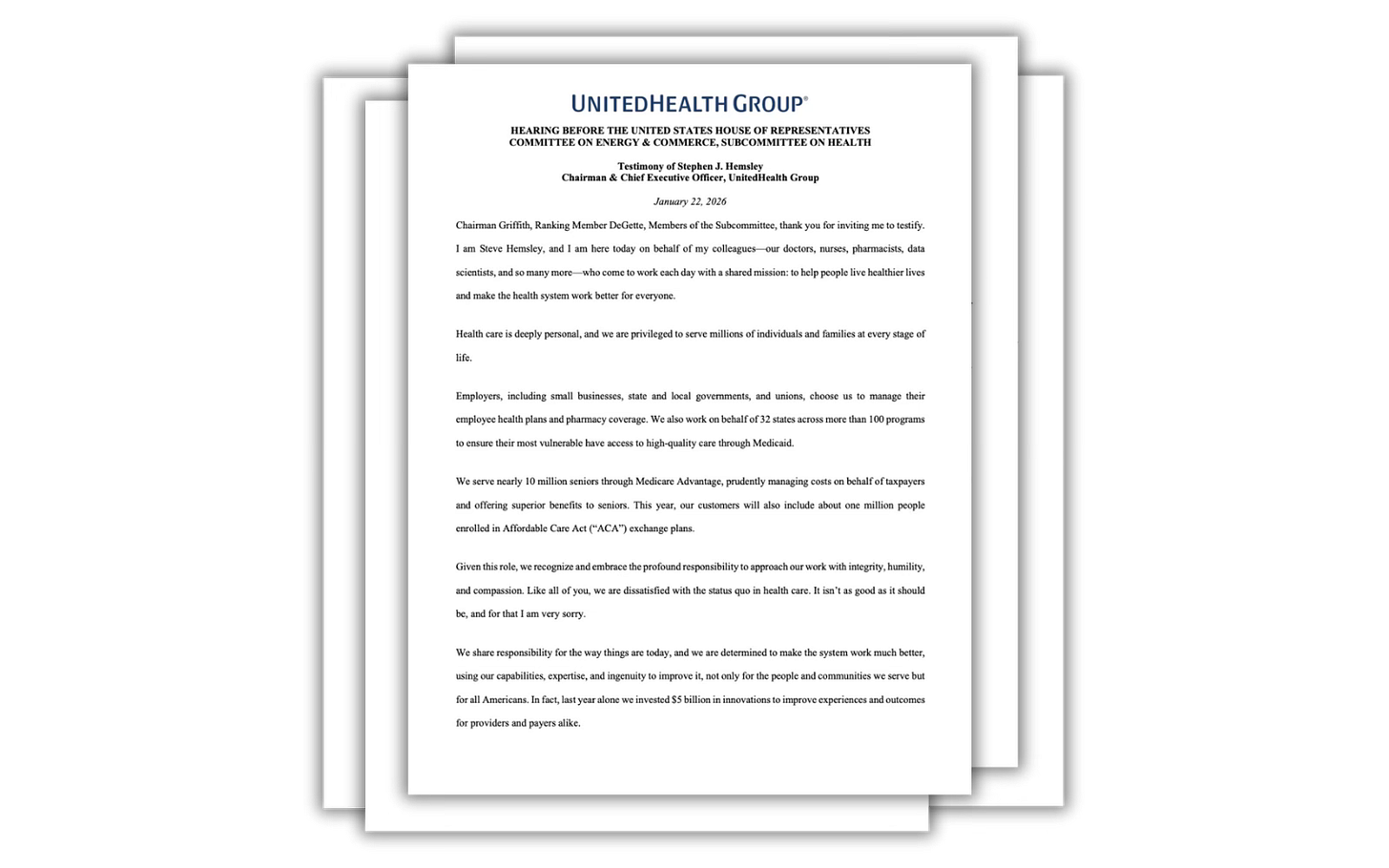

When I first testified before Congress, I was one of three people at the witness table, and all of us knew a lot about those plans – including Nancy Metcalf, who was senior program editor at Consumer Reports at the time. She in particular knew about the many shortcomings of those plans because she had heard horror story after horror story from people who had enrolled in a junk plan. She urged lawmakers to outlaw them – or at least make insurers put warning labels on them so people would know what they were buying and how little protection those plans provided. As Nancy testified:

Consumers need to be told, in big letters, what their policy’s out-of-pocket limit is, and right next to it, in equally big letters, if there are any expenses that don’t count towards that. They need to know approximately what their out-of-pocket costs will be for expensive treatments such as cancer chemotherapy, or heart surgery, or infusions of patented biologic drugs. They need, in other words, a fighting chance not to be ripped off by junk insurance.

As Reed Abelson of The New York Times reported last week, the administration’s proposal “involves a type of plan known as a catastrophic or skinny policy. While they may be appropriate for someone who is young and healthy, a sudden emergency room or unexpected hospital stay could cost thousands of dollars in unforeseen bills. People with chronic medical conditions also might have to pay for much – if not all – of their care out of their own pockets.”

Commonwealth Fund president Joseph Betancourt pointed out in the Times’ story that people are already struggling to pay for their medical care:

There’s no doubt that we have an affordability crisis. As we move forward to shifting more of the burden to patients, there’s a chance to really exacerbate the crisis.

Abelson noted that under the proposed rule change, insurance companies could not only sell the catastrophic plans on a multiyear basis once again, they could also sell plans that do not offer an established network of hospitals and doctors. “Those plans,” she wrote, “would instead pay a fixed amount for a doctor’s visit or procedure, and patients would have to pay any difference in price.”

Abelson also warned of another risk associated with sky-high deductibles: Because their premiums are lower, they “will end up being used as the benchmark for the level of subsidies in a given market. People who want a traditional plan with an established network could end up paying more because they receive a lower subsidy.”

As I mentioned, all of us will likely pay more for our coverage when these plans become legal again next year. As BenefitsPro reported last month – quoting the CEO of Community Health Systems, a big hospital chain – most patients who are currently in ACA plans with lower but still high deductibles and coinsurance requirements can’t pay very much of the “big out-of-pocket bills” hospitals have to send them.

It’s only going to get worse.