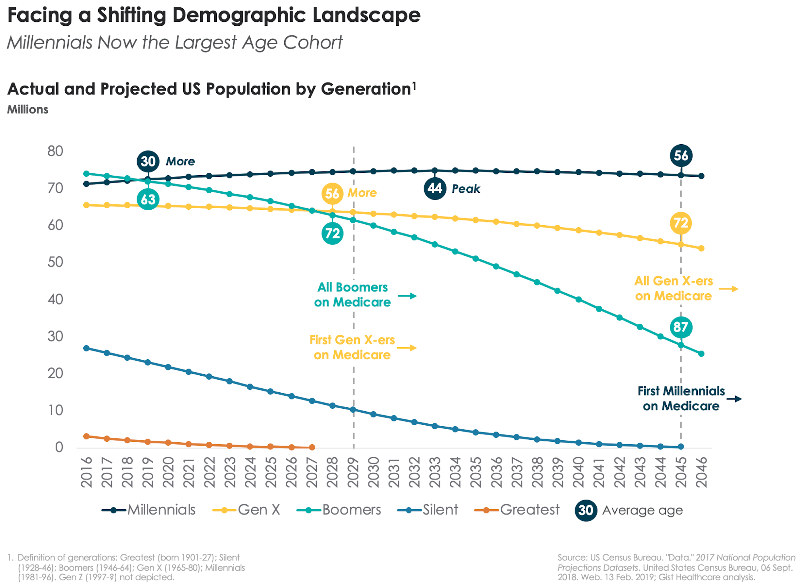

We spend an awful lot of time in healthcare talking about the Baby Boomers. No surprise, America has spent decades—six-and-a-half of them, to be exact—contending with the impact of this historically large generation on nearly every aspect of our national life. From politics to economics to culture, the Baby Boom reshaped almost every facet of our society, and healthcare has been no exception. The fact that over 10,000 Boomers join the Medicare ranks every day means they’ll have a transformative effect on how healthcare is delivered and paid for—up to and including the sustainability of the Medicare program itself. So it may come as a shock to Boomers to learn that, starting in 2019, it’s no longer All About Them. This year America passes a new milestone: Baby Boomers are now outnumbered by Millennials. As the chart below shows, Boomers (whose average age is now 63), will be surpassed this year by America’s new Largest Generation. Born between 1981 and 1996, the Millennials are now 30 years old on average, and there are 72.5M of them, compared to 72.0M Boomers—a gap that will continue to widen. (Thanks to immigration, we have another 14 years until we hit “peak” Millennial, according to Census Bureau projections.)

This demographic achievement alone ought to earn Millennials a participation trophy—obviously, not their first. (Forgive the sarcasm…we’re Gen X-ers, it’s what we do.) But this changing demographic landscape brings big implications for healthcare. Boomers are just entering their peak “senior care” consumption years now, and we’ll have a quarter-century or more of very expensive care to fund for a generation that is by all indications more riven with chronic disease but more likely to live into very old age than previous cohorts. That creates the imperative for population health approaches that allow care for seniors to be delivered in lower-acuity settings. At the same time, however, Millennials are really just entering the healthcare system. For the next several years, most of their care needs will be driven by having babies and caring for growing families. But just as the last of the Boomers get their Medicare cards in 2029, the Millennials will begin to enter their “upkeep” years—demanding a variety of diagnostics, surgeries, and procedures to keep them thriving. Who will pay for all of that specialty care, and where will it be delivered? Today’s health system planners would do well to begin to look ahead to future capacity needs, and economic models.

The Millennials bring dramatically different service expectations as well. This is a generation raised in the era of Amazon. One-click purchases, same-day delivery, frictionless transactions, personalized offerings, low institutional loyalty—all of that will shape the way this generation thinks about consuming healthcare, with huge implications for providers. This is a high-information generation, whose adult years have seen a pervasive shift from physical to digital commerce, and they’ll expect healthcare to follow that trend. Ask today’s pediatric providers how different the Millennials are as parent-consumers—you’ll quickly get the picture. Even as physicians, hospitals and others scramble to retool care delivery to more efficiently manage the swelling ranks of seniors, they’ll need to keep a close eye on the preferences of Millennials, upon whom their future fortunes will rely, and who won’t tolerate the hurry-up-and-wait ethos that still pervades American medicine.

(Spoiler alert: waiting in the wings is Gen Z, digital natives born in 1997 and after. Guess what? There’s even more of them!)