Cartoon – Have you hugged a Veteran today?

Vaccination is underway for the 2017-2018 seasonal flu, and next year will mark the 100-year anniversary of the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed roughly 40 million people. It is an opportune time to consider the possibility of pandemics – infections that go global and affect many people – and the importance of measures aimed at curbing them.

The 1918 pandemic was unusual in that it killed many healthy 20- to 40-year-olds, including millions of World War I soldiers. In contrast, people who die of the flu are usually under five years old or over 75.

The factors underlying the virulence of the 1918 flu are still unclear. Modern-day scientists sequenced the DNA of the 1918 virus from lung samples preserved from victims. However, this did not solve the mystery of why so many healthy young adults were killed.

I started investigating what happened to a young man who immigrated to the U.S. and was lost during World War I. Uncovering his story also brought me up to speed on hypotheses about why the immune systems of young adults in 1918 did not protect them from the flu.

Certificates picturing the goddess Columbia as a personification of the U.S. were awarded to men and women who died in service during World War I. One such certificate surfaced many decades later. This one honored Adolfo Sartini and was found by grandnephews who had never known him: Thomas, Richard and Robert Sartini.

The certificate was a message from the past. It called out to me, as I had just received the credential of certified genealogist and had spent most of my career as a scientist tracing a gene that regulates immune cells. What had happened to Adolfo?

To follow up, I posted a query on the “U.S. Militaria Forum.” Here, military history enthusiasts explained that the Army Corps of Engineers had trained men at Camp A. A. Humphreys in Virginia. Perhaps Adolfo had gone to this camp?A bit of sleuthing identified Adolfo’s ship listing, which showed that he was born in 1889 in Italy and immigrated to Boston in 1913. His draft card revealed that he worked at a country club in the Boston suburb of Newton. To learn more, Robert Sartini bought a 1930 book entitled “Newton War Memorial” on eBay. The book provided clues: Adolfo was drafted and ordered to report to Camp Devens, 35 miles from Boston, in March of 1918. He was later transferred to an engineer training regiment.

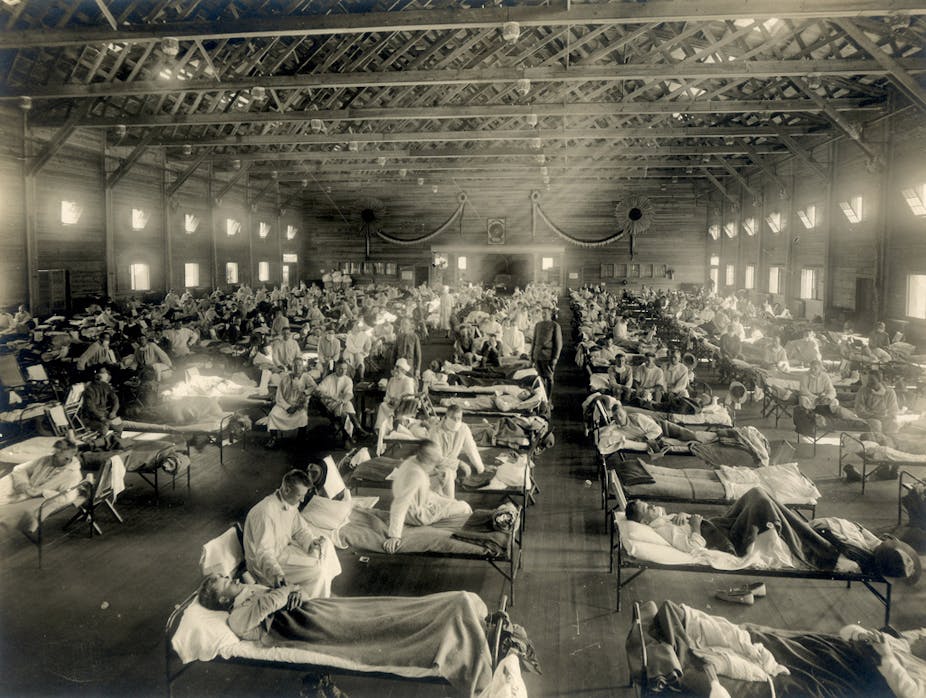

While a mild flu circulated during the spring of 1918, the deadly strain appeared on U.S. soil on Tuesday, Aug. 27, when three Navy dockworkers at Commonwealth Pier in Boston fell ill. Within 48 hours, dozens more men were infected. Ten days later, the flu was decimating Camp Devens. A renowned pathologist from Johns Hopkins, William Welch, was brought in. He realized that “this must be some new kind of infection or plague.” Viruses, minuscule agents that can pass through fine filters, were poorly understood.

With men mobilizing for World War I, the flu spread to military installations throughout the U.S. and to the general population. It hit Camp Humphreys in mid-September and killed more than 400 men there over the next month. This included Adolfo Sartini, age 29½. Adolfo’s body was brought back to Boston.

His grave is marked by a sculpture of the lower half of a toppled column, epitomizing his premature death.

The quest to understand the 1918 flu fueled many scientific advances, including the discovery of the influenza virus. However, the virus itself did not cause most of the deaths. Instead, a fraction of individuals infected by the virus were susceptible to pneumonia due to secondary infection by bacteria. In an era before antibiotics, pneumonia could be fatal.

Recent analyses revealed that deaths in 1918 were highest among individuals born in the years around 1889, like Adolfo. An earlier flu pandemic emerged then, and involved a virus that was likely of a different subtype than the 1918 strain. These analyses engendered a novel hypothesis, discussed below, about the susceptibility of healthy young adults in 1918.

Support for this hypothesis was seen with the emergence of the Hong Kong flu virus in 1968. It was in “Group 2” and had severe effects on people who had been children around the time of the 1918 “Group 1” flu.Exposure to an influenza virus at a young age increases resistance to a subsequent infection with the same or a similar virus. On the flip side, a person who is a child around the time of a pandemic may not be resistant to other, dissimilar viruses. Flu viruses fall into groups that are related evolutionarily. The virus that circulated when Adolfo was a baby was likely in what is called “Group 2,” whereas the 1918 virus was in “Group 1.” Adolfo would therefore not be expected to have a good ability to respond to this “Group 1” virus. In fact, exposure to the “Group 2” virus as a young child may have resulted in a dysfunctional response to the “Group 1” virus in 1918, exacerbating his condition.

What causes a common recurring illness to convert to a pandemic that is massively lethal to healthy individuals? Could it happen again? Until the reason for the death of young adults in 1918 is better understood, a similar scenario could reoccur. Experts fear that a new pandemic, of influenza or another infectious agent, could kill millions. Bill Gates is leading the funding effort to prevent this.

Flu vaccines are generated each year by monitoring the strains circulating months before flu season. A time lag of months allows for vaccine production. Unfortunately, because the influenza virus mutates rapidly, the lag also allows for the appearance of virus variants that are poorly targeted by the vaccine. In addition, flu pandemics often arise upon virus gene reassortment. This involves the joining together of genetic material from different viruses, which can occur suddenly and unpredictably.

An influenza virus is currently killing chickens in Asia, and has recently killed humans who had contact with chickens. This virus is of a subtype that has not been known to cause pandemics. It has not yet demonstrated the ability to be transmitted from person to person. However, whether this ability will arise during ongoing virus evolution cannot be predicted.

The chicken virus is in “Group 2.” Therefore, if it went pandemic, people who were children around the time of the 1968 “Group 2” Hong Kong flu might have some protection. I was born much earlier, and “Group 1” viruses were circulating when I was a child. If the next pandemic virus is in “Group 2,” I would probably not be resistant.

It’s early days for understanding how prior exposure affects flu susceptibility, especially for people born in the last three to four decades. Since 1977, viruses of both “Group 1” and “Group 2” have been in circulation. People born since then probably developed resistance to one or the other based on their initial virus exposures. This is good news for the near future since, if either a “Group 1” or a “Group 2” virus develops pandemic potential, some people should be protected. At the same time, if you are under 40 and another pandemic is identified, more information would be needed to hazard a guess as to whether you might be susceptible or resistant.

Veterans Day had its start as Armistice Day, marking the end of World War I hostilities. The holiday serves as an occasion to both honor those who have served in our armed forces and to ask whether we, as a nation, are doing right by them.

In recent years, that question has been directed most urgently at Veterans Affairs hospitals. Some critics are even calling for the dismantling of the whole huge system of hospitals and outpatient clinics.

President Obama signed a US$16 billion dollar bill to reduce wait times in 2014 to do things like hire more medical staff and open more facilities. And while progress has been made, much remains to be done. The system needs to improve access and timeliness of care, reduce often challenging bureaucratic hurdles and pay more attention to what front-line clinicians need to perform their duties well. There is no question that the VA health care system has to change, and it already has begun this process.

Over the past 25 years, I have been a medical student, chief resident, research fellow and practicing physician at four different VA hospitals. My research has led me to spend time in more than a dozen additional VA medical centers.

I know how VA hospitals work, and often have a hard time recognizing them as portrayed in today’s political and media environment. My experience is that the VA hospitals I know provide high-quality, compassionate care.

I don’t think most people have any sense of the size and scope of the VA system. Its 168 medical centers and more than one thousand outpatient clinics and other facilities serve almost nine million veterans a year, making it the largest integrated health care system in the country.

And many Americans may not know the role VA hospitals play in medical education. Two out of three medical doctors in practice in the U.S. today received some part of their training at a VA hospital.

The reason dates to the end of World War II. The VA faced a physician shortage, as almost 16 million Americans returned from war, many needing health care.

At the same time, many doctors returned from World War II and needed to complete their residency training. The VA and the nation’s medical schools thus became partners. In fact, the VA is the largest provider of health care training in the country, which increases the likelihood that trainees will consider working for the VA once they finish.

The VA network specializes in the treatment of such war-related problems as post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide prevention. It has, for example, pioneered the integration of primary care with mental health.

Many veterans live in rural parts of the U.S., are of advanced age and have chronic medical conditions that make travel challenging. So the VA is a national leader in telemedicine, with notable success in mental health care.

The VA’s research programs have made major breakthroughs in areas such as cardiac care, prosthetics and infection prevention.

I can vouch for the VA’s nationwide electronic medical records system, which for many years was at the cutting edge.

A case in point: Several years ago a veteran, in the middle of a cross-country trip, was driving through Michigan when he began feeling sick. Within minutes of his arrival at our VA hospital, we were able to access his records from a VA medical center over a thousand miles away, learn that he had a history of Addison disease, a rare condition, and provide prompt treatment.

I am therefore not surprised that the studies that have compared VA with non-VA care have found that the VA is, overall, as good as or better than the private sector. In fact, a recently published systematic review of 69 studies performed by RAND investigators concluded: “…the available data indicate overall comparable health care quality in VA facilities compared to non-VA facilities with regard to safety and effectiveness.”

The most remarkable aspect of VA hospitals, though, is the patient population, the men and women who have sacrificed for their country. They have a common bond. A patient explained it this way:

“The VA is different because everyone has done something similar, whether you were in World War II or Korea or Nam, like me. You’re not thrown into a pot with other people, which would happen at another kind of hospital.”

The people who work at VA hospitals have a special attitude toward their patients. It takes the form of respect and gratitude, of empathy, of a level of caring that is nothing short of love. You can see it in the extra services provided for patients who are often alone in the world, or too far from home to be visited.

Take a familiar scene: a medical student taking a patient for a walk or wheelchair ride on the hospital grounds. It is common for nurses to say “our veteran” when discussing a patient’s care with me.

Volunteers and chaplains rotate through VA hospitals on a regular basis, to a degree unknown in most community hospitals. The social work department is also more active. The patients are not always so patient, but these visitors persevere. “They’re a good bunch of people,” one veteran said of the staff. “I know because I’m irritable most of the time and they all get along with me.”

Physicians everywhere are under heavy pressure these days, in part because of the increase in the number of complex patients they care for. Yet I have spent hours observing doctors in VA hospitals around the country as they sit with patients, inquiring about their families and their military service, treating the veterans with respect and without haste.

Earlier this year, I cared for a veteran in his 50’s, a house painter, whom we diagnosed with cancer that had metastasized widely. We offered him chemotherapy, which could have given him an extra few months, but he chose hospice. He told me he wanted to go home to be with his wife and play the guitar. One of the songs he wanted to sing was “Knocking on Heaven’s Door.”

I was deeply moved. I liked and admired the man, and I was disturbed that we had been unable to save him. My medical student had the same feelings. Before the patient left, the student told me, “He shook my hand, looked me in the eyes, and said, ‘Thanks for being a warrior for me.’”

That’s the special kind of patient who shows up at a VA hospital. Every single one of them should have the special kind of care they deserve. And we must ensure that the care is superb on this and every day.