Cartoon – Sign of the Times (Pandemic)

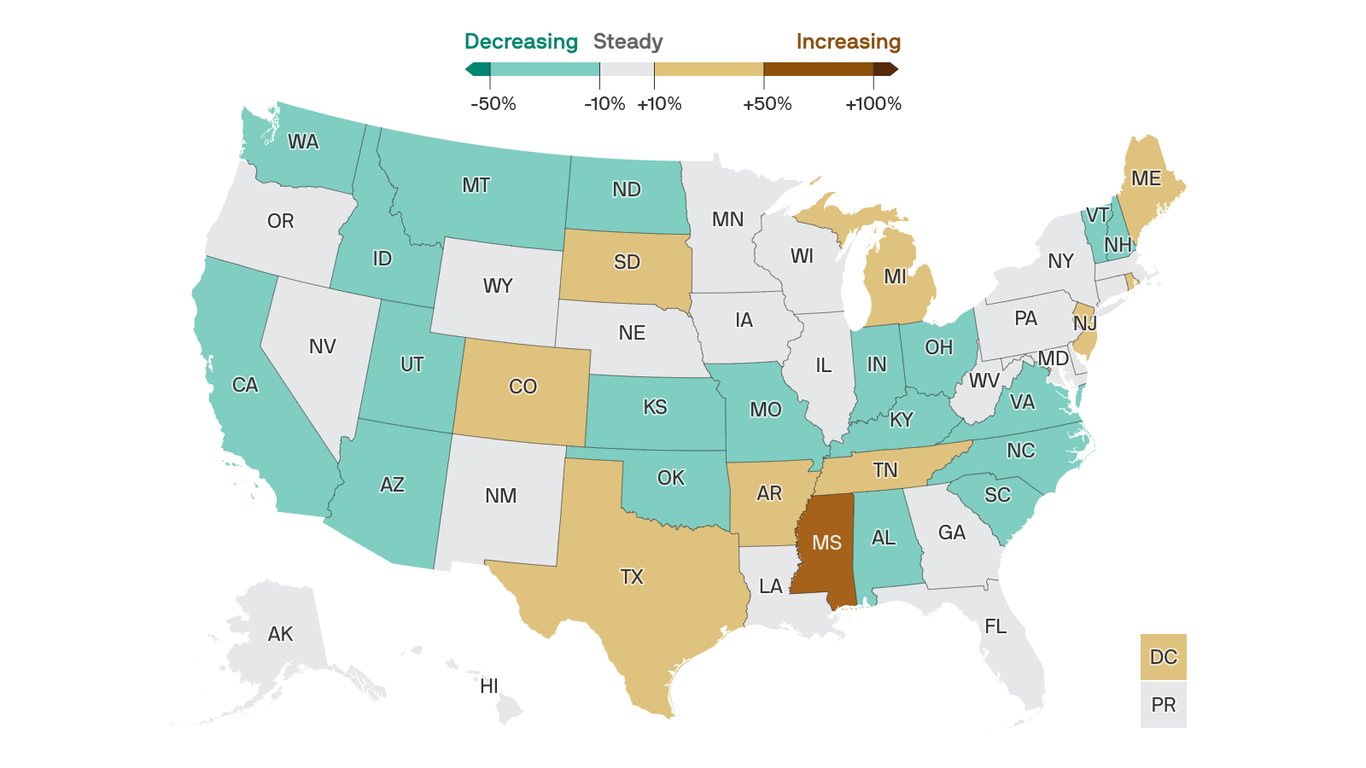

The U.S. may be on the verge of another surge in coronavirus cases, despite weeks of good news.

The big picture: Nationwide, progress against the virus has stalled. And some states are ditching their most important public safety measures even as their outbreaks are getting worse.

Where it stands: The U.S. averaged just under 65,000 new cases per day over the past week. That’s essentially unchanged from the week before, ending a six-week streak of double-digit improvements.

What we’re watching: Texas Gov. Greg Abbott on Tuesday rescinded the state’s mask mandate and declared that businesses will be able to operate at full capacity, saying risk-mitigation measures are no longer necessary because of the progress on vaccines.

How it works: If Americans let their guard down too soon, we could experience yet another surge — a fourth wave — before the vaccination campaign has had a chance to do its work.

What’s next: The bigger a foothold those variants can get, the harder it will be to escape COVID-19 — now or in the future.

The bottom line: Variants emerge when viruses spread widely, which is also how people die.

https://mailchi.mp/05e4ff455445/the-weekly-gist-february-26-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

Although the nation reached a grim and long-dreaded milestone on Monday, surpassing 500,000 lives lost to COVID—more than were killed in two World Wars and the Vietnam conflict combined—the news this week was mostly good, as key indicators of the pandemic’s severity continued to rapidly improve.

Over the past two weeks, hospitalizations for COVID were down 30 percent, deaths were down 22 percent, and new cases declined by 32 percent—the lowest levels since late October. This week’s numbers declined somewhat more slowly than last week’s, leading Dr. Rachel Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to caution people against letting their guard down just yet: “Things are tenuous. Now is not the time to relax restrictions.” Of particular concern are new variants of the coronavirus that have emerged in numerous states, including one in New York and another in California, that may be more contagious than the original virus.

The best news of the week was surely a report from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) evaluating the new, single-shot COVID vaccine from Johnson & Johnson (J&J), showing it to be highly effective at preventing severe disease, hospitalization, and death caused by COVID, including variants. On Friday, a panel of outside experts met to assess whether to approve the J&J vaccine for emergency use, which would make it the third in the nation’s arsenal of COVID vaccines. If approved, the vaccine will be rolled out next week, according to the White House, with up to 4M doses available immediately.

The sooner the better: new data show that since vaccinations began in late December, new cases among nursing home residents have fallen more than 80 percent—a hopeful glimpse at the future that lies ahead for the general population once vaccines become widely available.

In recent weeks, U.S. coronavirus case data — long a closely-watched barometer of the pandemic’s severity — has sent some encouraging signals: The rate of newly recorded infections is plummeting from coast to coast and the worst surge yet is finally relenting. But scientists are split on why, exactly, it is happening.

Some point to the quickening pace of coronavirus vaccine administration, some say it’s because of the natural seasonal ebb of respiratory viruses and others chalk it up to social distancing measures.

And every explanation is appended with two significant caveats: The country is still in a bad place, continuing to notch more than 90,000 new cases every day, and recent progress could still be imperiled, either by new fast-spreading virus variants or by relaxed social distancing measures.

The rolling daily average of new infections in the United States hit its all-time high of 248,200 on Jan. 12, according to data gathered and analyzed by The Washington Post. Since then, the number has dropped every day, hitting 91,000 on Sunday, its lowest level since November.

A former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention endorsed the idea that Americans are now seeing the effect of their good behavior — not of increased vaccinations.

“I don’t think the vaccine is having much of an impact at all on case rates,” Tom Frieden said in an interview Sunday on CNN’s “Fareed Zakaria GPS.” “It’s what we’re doing right: staying apart, wearing masks, not traveling, not mixing with others indoors.”

However, Frieden noted, the country’s numbers are still higher than they were during the spring and summer virus waves and “we’re nowhere near out of the woods.”

“We’ve had three surges,” Frieden said. “Whether or not we have a fourth surge is up to us, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.”

The current CDC director, Rochelle Walensky, said in a round of TV interviews Sunday morning that behavior will be crucial to averting yet another spike in infections and that it is far too soon for states to be rescinding mask mandates. Walensky also noted the declining numbers but said cases are still “more than two-and-a-half-fold times what we saw over the summer.”

“It’s encouraging to see these trends coming down, but they’re coming down from an extraordinarily high place,” she said on NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

Researchers at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, publisher of a popular coronavirus model, are among those who attribute declining cases to vaccines and the virus’s seasonality, which scientists have said may allow it to spread faster in colder weather.

In the IHME’s most recent briefing, published Friday, the authors write that cases have “declined sharply,” dropping nearly 50 percent since early January.

“Two [factors] are driving down transmission,” the briefing says. “1) the continued scale-up of vaccination helped by the fraction of adults willing to accept the vaccine reaching 71 percent, and 2) declining seasonality, which will contribute to declining transmission potential from now until August.”

The model predicts 152,000 more covid-19 deaths by June 1, but projects that the vaccine rollout will save 114,000 lives.

In the past week, the country collectively administered 1.62 million vaccine doses per day, according to The Washington Post’s analysis of state and federal data. It was the best week yet for the shots, topping even President Biden’s lofty goal of 1.5 million vaccinations per day.

Nearly 40 million people have received at least their first dose of a coronavirus vaccine, about 12 percent of the U.S. population. Experts have said that 70 percent to 90 percent of people need to have immunity, either through vaccination or prior infection, to quash the pandemic. And some leading epidemiologists have agreed with Frieden, saying that not enough people are vaccinated to make such a sizable dent in the case rates.

A fourth, less optimistic explanation has also emerged: More new cases are simply going undetected. On Twitter, Eleanor Murray, a professor of epidemiology at Boston University School of Public Health, said an increased focus on vaccine distribution and administration could be making it harder to get tested.

“I worry that it’s at least partly an artifact of resources being moved from testing to vaccination,” Murray said of the declines.

The Covid Tracking Project, which compiles and publishes data on coronavirus testing, has indeed observed a steady recent decrease in tests, from more than 2 million per day in mid-January to about 1.6 million a month later. The project’s latest update blames this dip on “a combination of reduced demand as well as reduced availability or accessibility of testing.”

“Demand for testing may have dropped because fewer people are sick or have been exposed to infected individuals, but also perhaps because testing isn’t being promoted as heavily,” the authors write.

They note that a backlog of tests over the holidays probably produced an artificial spike of reported tests in early January, but that even when adjusted, it’s still “unequivocally the wrong direction for a country that needs to understand the movements of the virus during a slow vaccine rollout and the spread of multiple new variants.”

Where most experts agree: The mutated variants of the virus pose perhaps the biggest threat to the country’s recovery. One is spreading rapidly and another, known as B.1.351, contains a mutation that may help the virus partly evade natural and vaccine-induced antibodies.

Fewer than 20 cases have been reported in the United States, but a critically ill man in France underscores the variant’s potentially dangerous consequences. The 58-year-old had a mild coronavirus infection in September and the B.1.351 strain reinfected him four months later.

No matter what’s causing the current downturn in new infections, experts have urged Americans to avoid complacency.

“Masks, distancing, ventilation, avoiding gatherings, getting vaccinated when eligible. These are the tools we have to continue the long trip down the tall mountain,” Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, said on Twitter. “The variants may throw us a curve ball, but if we keep driving down transmission we can get to a better place.”

As both vaccinations and acquired immunity spread, life will likely settle into a new normal that will resemble pre-COVID-19 days— with some major twists.

The big picture: While hospitalizations and deaths are tamped down, the novel coronavirus should recede as a mortal threat to the world. But a lingering pool of unvaccinated people — and the virus’ own ability to mutate — will ensure SARS-CoV-2 keeps circulating at some level, meaning some precautions will be kept in place for years.

Driving the news: On Tuesday, Johnson & Johnson CEO Alex Gorsky told CNBC that people might well need a new coronavirus vaccine annually in the years ahead, much as they do now for the flu.

Be smart: That sounds like bad news — and indeed, it’s much less ideal than a world in which vaccination or infection conferred close to lifelong immunity and SARS-CoV-2 could be definitively conquered like smallpox.

Details: From studying what happened after new viruses emerged in the past, scientists predict SARS-CoV-2 will eventually become endemic, most likely in a seasonal pattern similar to the kind of coronaviruses that cause the common cold.

Yes, but: The existence of a stubborn pool of Americans who say they won’t get vaccinated — as well as the fact that it may take far longer for children, whom the vaccines have yet to be tested on, to get coverage — will give the virus longer legs than it would otherwise have.

What’s next: This means we can expect the K-shaped recovery that has marked the pandemic to continue, says Ben Pring, who leads Cognizant’s Center for the Future of Work.

The catch: That’s not all bad — the measures put in place to slow COVID-19 have stomped the flu and other seasonal respiratory viruses, and if we can hold onto some of those benefits in the future, we can save tens of thousands of lives and billions of dollars.

“If we go back to ‘normal,’ then we have failed.”

— Mark Sendak

What to watch: Whether the vaccine rollout can be adapted to reach hard to find and hard to persuade populations.

The bottom line: While SARS-CoV-2 has proven it can adapt to a changing environment, so can we. But we have to do so in a way that is fairer than our experience of the pandemic has been so far.

Most seniors have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine yet, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Why it matters: There’s simply not enough vaccine available right now to take on every priority, Axios’ Marisa Fernandez writes.

By the numbers: In the first month of vaccinations, about 29% of recipients were 65 or older, per KFF.

Where it stands: West Virginia has vaccinated the most seniors at 34%, thanks to a focused effort in nursing homes.

Yes, but: Demographic data aren’t available in some states and cities, which will make it hard to track how well the U.S. is addressing high-risk groups as more people become eligible.

In the seven states hit hardest by the pandemic, more than 1 in every 500 residents have died from the coronavirus.

Why it matters: The staggering death toll speaks to America’s failure to control the virus.

Details: In New Jersey, which has the highest death rate in the nation, 1 out of every 406 residents has died from the virus. In neighboring New York, 1 out of every 437 people has died.

States in the middle of the pack have seen a death rate of around 1 in 800 dead.

The bottom line: Americans will keep dying as vaccinations ramp up, and more transmissible variants of the coronavirus could cause the outbreak to get worse before it gets better.

https://mailchi.mp/85f08f5211a4/the-weekly-gist-february-5-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

Doctors and scientists have been relieved that the dreaded “twindemic”—the usual winter spike of seasonal influenza superimposed on the COVID pandemic—did not materialize.

In fact, flu cases are at one of the lowest levels ever recorded, with just 155 flu-related hospitalizations this season (compared to over 490K in 2019). A new piece in the Atlantic looks at the long-term ramifications of a year without the flu.

Public health measures like masking and handwashing have surely lowered flu transmission, but scientists remain uncertain why flu cases have flatlined as COVID-19, which spreads via the same mechanisms, surged.

Children are a much greater vector for influenza, and reduced mingling in schools and childcare likely slowed spread. Perhaps the shutdown in travel slowed the viruses’ ability to hop a ride from continent to continent, and the cancellation of gatherings further dampened transmission.

Nor are scientists sure what to expect next year. Optimists hope that record-low levels of flu could take a strain out of circulation. But others warn that flu could return with a vengeance, as the virus continues to mutate while population immunity declines.

Researchers developing next year’s vaccines, meanwhile, face a lack of data on what strains and mutations to target—although many hope the mRNA technologies that proved effective for COVID will enable more agile flu vaccine development in the future.

Regardless, renewed vigilance in flu prevention and vaccination next fall will be essential, as a COVID-fatigued population will be inclined to breathe a sigh of relief as the current pandemic comes under control.

https://mailchi.mp/85f08f5211a4/the-weekly-gist-february-5-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

A family member in her 70s called with the great news that she received her first dose of the COVID vaccine this week. She mentioned that she was hoping to plan a vacation in the spring with a friend who had also been vaccinated, but her doctor told her it would still be safest to hold off booking travel for now: “I was surprised she wasn’t more positive about it. It’s the one thing I’ve been looking forward to for months, if I was lucky enough to get the shot.”

It’s not easy to find concrete expert guidance for what it is safe (or safer?) to do after receiving the COVID vaccine. Of course, patients need to wait a minimum of two weeks after receiving their second shot of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines to develop full immunity.

But then what? Yes, we all need to continue to wear masks in public, since vaccines haven’t been proven to reduce or eliminate COVID transmission—and new viral variants up the risk of transmission. But should vaccinated individuals feel comfortable flying on a plane? Visiting family? Dining indoors? Finally going to the dentist?

It struck us that the tone of much of the available guidance speaks to public health implications, rather than individual decision-making. Take this tweet from CDC director Dr. Rochelle Walensky. A person over 65 asked her if she could drive to visit her grandchildren, whom she hasn’t seen for a year, two months after receiving her second shot. Walensky replied, “Even if you’ve been vaccinated, we still recommend against traveling until we have more data to suggest vaccination limits the spread of COVID-19.”

From a public health perspective, this may be correct, but for an individual, it falls flat. This senior has followed all the rules—if the vaccine doesn’t enable her to safely see her grandchild, what will? It’s easy to see how the expert guidance could be interpreted as “nothing will change, even after you’ve been vaccinated.”

Debates about masking showed us that in our individualistic society, public health messaging about slowing transmission and protecting others sadly failed to make many mask up.

The same goes for vaccines: most Americans are motivated to get their vaccine so that they personally don’t die, and so they can resume a more normal life, not by the altruistic desire to slow the spread of COVID in the community and achieve “herd immunity”.

In addition to focusing on continued risk, educating Americans on how the vaccinated can make smart decisions will motivate as many people as possible to get their shots.