Category Archives: Crisis

Are You A Carrot, Egg or Coffee?

Granddaughter Says Life Is Too Hard. That’s When Grandma Pulls Out A Carrot, Egg & Coffee

As the story begins, a woman goes to visit her grandmother. She is stressed and frustrated by the way that her life has been going— in a way that many can relate. No sooner is one problem dealt with than another one rises in its place.

The woman tells her grandmother that she’s reaching the end of her rope and doesn’t know how she can go on.

Without a word, the grandmother goes to her kitchen, fills three pots with water, and puts the pots on the stove to boil. Once the water is bubbling away, the grandmother puts a few carrots in one pot, several eggs in the second pot, and ground coffee beans in the third.

After about twenty minutes or so, the grandmother turns off the heat and puts the contents of each pot in a bowl.

She then asks her granddaughter what she sees.

The answer seems obvious. “Carrots, eggs, and coffee,” the granddaughter replies.

The grandmother then tells her granddaughter to feel the softened, boiled carrots, to crack the hard-boiled egg and look at it, and to take a sip of the coffee.

Having done so, the granddaughter asks what it all means. The story continues:

“Her grandmother explained that each of these objects had faced the same adversity — boiling water — but each reacted differently.

“The carrot went in strong, hard and unrelenting. However, after being subjected to the boiling water, it softened and became weak. The egg had been fragile. Its thin outer shell had protected its liquid interior. But, after sitting through the boiling water, its inside became hardened.

“The ground coffee beans were unique, however. After they were in the boiling water, they had changed the water.”

The question for the granddaughter — and for the reader as well — is which one represents how you respond to adversity. Are you the egg? The carrots? Or the coffee?

“Think of this: Which am I? Am I the carrot that seems strong, but with pain and adversity? Do I wilt and become soft and lose my strength?

“Am I the egg that starts with a malleable heart, but changes with the heat? Did I have a fluid spirit, but after a death, a breakup, a financial hardship or some other trial, have I become hardened and stiff? Does my shell look the same, but on the inside am I bitter and tough with a stiff spirit and a hardened heart?

“Or am I like the coffee bean? The bean actually changes the hot water, the very circumstance that brings the pain. When the water gets hot, it releases the fragrance and flavor of your life. If you are like the bean, when things are at their worst, you get better and change the situation around you. When the hours are the darkest and trials are their greatest, do you elevate to another level?”

Of course, the question is posed not just as a way to examine how you respond to adversity now, but in order to learn how to adapt in the future.

We are not permanently carrots or eggs or coffee. Perhaps you have responded as an egg before. Perhaps you’re currently feeling a bit carrot-y. But that doesn’t mean that you can’t make a change.

A mounting wave of post-COVID CEO retirements

https://mailchi.mp/097beec6499c/the-weekly-gist-april-30-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

A recently retired health system CEO pointed us to a working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, which indicates that leading an organization through an industry downturn takes a year and a half off a CEO’s lifespan.

It’s not surprising, he said, that given the stress of the past year, we will face a big wave of retirements of tenured health system CEOs as their organizations exit the COVID crisis. Part of the turnover is generational, with many Baby Boomers nearing retirement age, and some having delayed their exits to mitigate disruption during the pandemic.

As they look toward the next few years and decide when to exit, many are also contemplating their legacies. One shared, “COVID was enormously challenging, but we are coming out of it with great pride, and a sense of accomplishment that we did things we never thought possible.

Do I want to leave on that note, or after three more years of cost cutting?” All agreed that a different skill set will be required for the next generation of leaders. The next-generation CEOs must build diverse teams capable of succeeding in a disruptive marketplace, and think differently about the role of the health system.

“I’m glad I’m retiring soon,” one executive noted. “I’m not sure I have the experience to face what’s coming. You won’t succeed by just being better at running the old playbook.” Compelling candidates exist in many systems, and assessing who performed best under the “stress test” of COVID should prove a helpful way to identify them.

In scramble to respond to Covid-19, hospitals turned to models with high risk of bias

Of 26 health systems surveyed by MedCity News, nearly half used automated tools to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic, but none of them were regulated. Even as some hospitals continued using these algorithms, experts cautioned against their use in high-stakes decisions.

A year ago, Michigan Medicine faced a dire situation. In March of 2020, the health system predicted it would have three times as many patients as its 1,000-bed capacity — and that was the best-case scenario. Hospital leadership prepared for this grim prediction by opening a field hospital in a nearby indoor track facility, where patients could go if they were stable, but still needed hospital care. But they faced another predicament: How would they decide who to send there?

Two weeks before the field hospital was set to open, Michigan Medicine decided to use a risk model developed by Epic Systems to flag patients at risk of deterioration. Patients were given a score of 0 to 100, intended to help care teams determine if they might need an ICU bed in the near future. Although the model wasn’t developed specifically for Covid-19 patients, it was the best option available at the time, said Dr. Karandeep Singh, an assistant professor of learning health sciences at the University of Michigan and chair of Michigan Medicine’s clinical intelligence committee. But there was no peer-reviewed research to show how well it actually worked.

Researchers tested it on over 300 Covid-19 patients between March and May. They were looking for scores that would indicate when patients would need to go to the ICU, and if there was a point where patients almost certainly wouldn’t need intensive care.

“We did find a threshold where if you remained below that threshold, 90% of patients wouldn’t need to go to the ICU,” Singh said. “Is that enough to make a decision on? We didn’t think so.”

But if the number of patients were to far exceed the health system’s capacity, it would be helpful to have some way to assist with those decisions.

“It was something that we definitely thought about implementing if that day were to come,” he said in a February interview.

Thankfully, that day never came.

The survey

Michigan Medicine is one of 80 hospitals contacted by MedCity News between January and April in a survey of decision-support systems implemented during the pandemic. Of the 26 respondents, 12 used machine learning tools or automated decision systems as part of their pandemic response. Larger hospitals and academic medical centers used them more frequently.

Faced with scarcities in testing, masks, hospital beds and vaccines, several of the hospitals turned to models as they prepared for difficult decisions. The deterioration index created by Epic was one of the most widely implemented — more than 100 hospitals are currently using it — but in many cases, hospitals also formulated their own algorithms.

They built models to predict which patients were most likely to test positive when shortages of swabs and reagents backlogged tests early in the pandemic. Others developed risk-scoring tools to help determine who should be contacted first for monoclonal antibody treatment, or which Covid patients should be enrolled in at-home monitoring programs.

MedCity News also interviewed hospitals on their processes for evaluating software tools to ensure they are accurate and unbiased. Currently, the FDA does not require some clinical decision-support systems to be cleared as medical devices, leaving the developers of these tools and the hospitals that implement them responsible for vetting them.

Among the hospitals that published efficacy data, some of the models were only evaluated through retrospective studies. This can pose a challenge in figuring out how clinicians actually use them in practice, and how well they work in real time. And while some of the hospitals tested whether the models were accurate across different groups of patients — such as people of a certain race, gender or location — this practice wasn’t universal.

As more companies spin up these models, researchers cautioned that they need to be designed and implemented carefully, to ensure they don’t yield biased results.

An ongoing review of more than 200 Covid-19 risk-prediction models found that the majority had a high risk of bias, meaning the data they were trained on might not represent the real world.

“It’s that very careful and non-trivial process of defining exactly what we want the algorithm to be doing,” said Ziad Obermeyer, an associate professor of health policy and management at UC Berkeley who studies machine learning in healthcare. “I think an optimistic view is that the pandemic functions as a wakeup call for us to be a lot more careful in all of the ways we’ve talked about with how we build algorithms, how we evaluate them, and what we want them to do.”

Algorithms can’t be a proxy for tough decisions

Concerns about bias are not new to healthcare. In a paper published two years ago, Obermeyer found a tool used by several hospitals to prioritize high-risk patients for additional care resources was biased against Black patients. By equating patients’ health needs with the cost of care, the developers built an algorithm that yielded discriminatory results.

More recently, a rule-based system developed by Stanford Medicine to determine who would get the Covid-19 vaccine first ended up prioritizing administrators and doctors who were seeing patients remotely, leaving out most of its 1,300 residents who had been working on the front lines. After an uproar, the university attributed the errors to a “complex algorithm,” though there was no machine learning involved.

Both examples highlight the importance of thinking through what exactly a model is designed to do — and not using them as a proxy to avoid the hard questions.

“The Stanford thing was another example of, we wanted the algorithm to do A, but we told it to do B. I think many health systems are doing something similar,” Obermeyer said. “You want to give the vaccine first to people who need it the most — how do we measure that?”

The urgency that the pandemic created was a complicating factor. With little information and few proven systems to work with in the beginning, health systems began throwing ideas at the wall to see what works. One expert questioned whether people might be abdicating some responsibility to these tools.

“Hard decisions are being made at hospitals all the time, especially in this space, but I’m worried about algorithms being the idea of where the responsibility gets shifted,” said Varoon Mathur, a technology fellow at NYU’s AI Now Institute, in a Zoom interview. “Tough decisions are going to be made, I don’t think there are any doubts about that. But what are those tough decisions? We don’t actually name what constraints we’re hitting up against.”

The wild, wild west

There currently is no gold standard for how hospitals should implement machine learning tools, and little regulatory oversight for models designed to support physicians’ decisions, resulting in an environment that Mathur described as the “wild, wild west.”

How these systems were used varied significantly from hospital to hospital.

Early in the pandemic, Cleveland Clinic used a model to predict which patients were most likely to test positive for the virus as tests were limited. Researchers developed it using health record data from more than 11,000 patients in Ohio and Florida, including 818 who tested positive for Covid-19. Later, they created a similar risk calculator to determine which patients were most likely to be hospitalized for Covid-19, which was used to prioritize which patients would be contacted daily as part of an at-home monitoring program.

Initially, anyone who tested positive for Covid-19 could enroll in this program, but as cases began to tick up, “you could see how quickly the nurses and care managers who were running this program were overwhelmed,” said Dr. Lara Jehi, Chief Research Information Officer at Cleveland Clinic. “When you had thousands of patients who tested positive, how could you contact all of them?”

While the tool included dozens of factors, such as a patient’s age, sex, BMI, zip code, and whether they smoked or got their flu shot, it’s also worth noting that demographic information significantly changed the results. For example, a patient’s race “far outweighs” any medical comorbidity when used by the tool to estimate hospitalization risk, according to a paper published in Plos One. Cleveland Clinic recently made the model available to other health systems.

Others, like Stanford Health Care and 731-bed Santa Clara County Medical Center, started using Epic’s clinical deterioration index before developing their own Covid-specific risk models. At one point, Stanford developed its own risk-scoring tool, which was built using past data from other patients who had similar respiratory diseases, such as the flu, pneumonia, or acute respiratory distress syndrome. It was designed to predict which patients would need ventilation within two days, and someone’s risk of dying from the disease at the time of admission.

Stanford tested the model to see how it worked on retrospective data from 159 patients that were hospitalized with Covid-19, and cross-validated it with Salt Lake City-based Intermountain Healthcare, a process that took several months. Although this gave some additional assurance — Salt Lake City and Palo Alto have very different populations, smoking rates and demographics — it still wasn’t representative of some patient groups across the U.S.

“Ideally, what we would want to do is run the model specifically on different populations, like on African Americans or Hispanics and see how it performs to ensure it’s performing the same for different groups,” Tina Hernandez-Boussard, an associate professor of medicine, biomedical data science and surgery at Stanford, said in a February interview. “That’s something we’re actively seeking. Our numbers are still a little low to do that right now.”

Stanford planned to implement the model earlier this year, but ultimately tabled it as Covid-19 cases fell.

‘The target is moving so rapidly’

Although large medical centers were more likely to have implemented automated systems, there were a few notable holdouts. For example, UC San Francisco Health, Duke Health and Dignity Health all said they opted not to use risk-prediction models or other machine learning tools in their pandemic responses.

“It’s pretty wild out there and I’ll be honest with you — the dynamics are changing so rapidly,” said Dr. Erich Huang, chief officer for data quality at Duke Health and director of Duke Forge. “You might have a model that makes sense for the conditions of last month but do they make sense for the conditions of next month?”

That’s especially true as new variants spread across the U.S., and more adults are vaccinated, changing the nature and pace of the disease. But other, less obvious factors might also affect the data. For instance, Huang pointed to big differences in social mobility across the state of North Carolina, and whether people complied with local restrictions. Differing social and demographic factors across communities, such as where people work and whether they have health insurance, can also affect how a model performs.

“There are so many different axes of variability, I’d feel hard pressed to be comfortable using machine learning or AI at this point in time,” he said. “We need to be careful and understand the stakes of what we’re doing, especially in healthcare.”

Leadership at one of the largest public hospitals in the U.S., 600-bed LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, also steered away from using predictive models, even as it faced an alarming surge in cases over the winter months.

At most, the hospital used alerts to remind physicians to wear protective equipment when a patient has tested positive for Covid-19.

“My impression is that the industry is not anywhere near ready to deploy fully automated stuff just because of the risks involved,” said Dr. Phillip Gruber, LAC+USC’s chief medical information officer. “Our institution and a lot of institutions in our region are still focused on core competencies. We have to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars.”

When the data itself is biased

Developers have to contend with the fact that any model developed in healthcare will be biased, because the data itself is biased; how people access and interact with health systems in the U.S. is fundamentally unequal.

How that information is recorded in electronic health record systems (EHR) can also be a source of bias, NYU’s Mathur said. People don’t always self-report their race or ethnicity in a way that fits neatly within the parameters of an EHR. Not everyone trusts health systems, and many people struggle to even access care in the first place.

“Demographic variables are not going to be sharply nuanced. Even if they are… in my opinion, they’re not clean enough or good enough to be nuanced into a model,” Mathur said.

The information hospitals have had to work with during the pandemic is particularly messy. Differences in testing access and missing demographic data also affect how resources are distributed and other responses to the pandemic.

“It’s very striking because everything we know about the pandemic is viewed through the lens of number of cases or number of deaths,” UC Berkeley’s Obermeyer said. “But all of that depends on access to testing.”

At the hospital level, internal data wouldn’t be enough to truly follow whether an algorithm to predict adverse events from Covid-19 was actually working. Developers would have to look at social security data on mortality, or whether the patient went to another hospital, to track down what happened.

“What about the people a physician sends home — if they die and don’t come back?” he said.

Researchers at Mount Sinai Health System tested a machine learning tool to predict critical events in Covid-19 patients — such as dialysis, intubation or ICU admission — to ensure it worked across different patient demographics. But they still ran into their own limitations, even though the New York-based hospital system serves a diverse group of patients.

They tested how the model performed across Mount Sinai’s different hospitals. In some cases, when the model wasn’t very robust, it yielded different results, said Benjamin Glicksberg, an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at Mount Sinai and a member of its Hasso Plattner Institute for Digital Health.

They also tested how it worked in different subgroups of patients to ensure it didn’t perform disproportionately better for patients from one demographic.

“If there’s a bias in the data going in, there’s almost certainly going to be a bias in the data coming out of it,” he said in a Zoom interview. “Unfortunately, I think it’s going to be a matter of having more information that can approximate these external factors that may drive these discrepancies. A lot of that is social determinants of health, which are not captured well in the EHR. That’s going to be critical for how we assess model fairness.”

Even after checking for whether a model yields fair and accurate results, the work isn’t done yet. Hospitals must continue to validate continuously to ensure they’re still working as intended — especially in a situation as fast-moving as a pandemic.

A bigger role for regulators

All of this is stirring up a broader discussion about how much of a role regulators should have in how decision-support systems are implemented.

Currently, the FDA does not require most software that provides diagnosis or treatment recommendations to clinicians to be regulated as a medical device. Even software tools that have been cleared by the agency lack critical information on how they perform across different patient demographics.

Of the hospitals surveyed by MedCity News, none of the models they developed had been cleared by the FDA, and most of the external tools they implemented also hadn’t gone through any regulatory review.

In January, the FDA shared an action plan for regulating AI as a medical device. Although most of the concrete plans were around how to regulate algorithms that adapt over time, the agency also indicated it was thinking about best practices, transparency, and methods to evaluate algorithms for bias and robustness.

More recently, the Federal Trade Commission warned that it could crack down on AI bias, citing a paper that AI could worsen existing healthcare disparities if bias is not addressed.

“My experience suggests that most models are put into practice with very little evidence of their effects on outcomes because they are presumed to work, or at least to be more efficient than other decision-making processes,” Kellie Owens, a researcher for Data & Society, a nonprofit that studies the social implications of technology, wrote in an email. “I think we still need to develop better ways to conduct algorithmic risk assessments in medicine. I’d like to see the FDA take a much larger role in regulating AI and machine learning models before their implementation.”

Developers should also ask themselves if the communities they’re serving have a say in how the system is built, or whether it is needed in the first place. The majority of hospitals surveyed did not share with patients if a model was used in their care or involve patients in the development process.

In some cases, the best option might be the simplest one: don’t build.

In the meantime, hospitals are left to sift through existing published data, preprints and vendor promises to decide on the best option. To date, Michigan Medicine’s paper is still the only one that has been published on Epic’s Deterioration Index.

Care teams there used Epic’s score as a support tool for its rapid response teams to check in on patients. But the health system was also looking at other options.

“The short game was that we had to go with the score we had,” Singh said. “The longer game was, Epic’s deterioration index is proprietary. That raises questions about what is in it.”

India’s devastating outbreak is driving the global coronavirus surge

NEW DELHI — More than a year after the pandemic began, infections worldwide have surpassed their previous peak. The average number of coronavirus cases reported each day is now higher than it has ever been.

“Cases and deaths are continuing to increase at worrying rates,” said World Health Organization chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on Friday.

A major reason for the increase: the ferocity of India’s second wave. The country accounts for about one in three of all new cases.

It wasn’t supposed to happen like this. Earlier this year, India appeared to be weathering the pandemic. The number of daily cases dropped below 10,000 and the government launched a vaccination drive powered by locally made vaccines.

But experts say that changes in behavior and the influence of new variants have combined to produce a tidal wave of new cases.

India is adding more than 250,000 new infections a day — and if current trends continue, that figure could soar to 500,000 within a month, said Bhramar Mukherjee, a biostatistician at the University of Michigan.

While infections are rising around the country, some places are bearing the brunt of the surge. Six states and Delhi, the nation’s capital, account for about two-thirds of new daily cases. Maharashtra, home to India’s financial hub, Mumbai, represents about a quarter of the nation’s total.

Mohammad Shahzad, a 40-year-old accountant, was one of many desperately seeking care. He developed a fever and grew breathless on the afternoon of April 15. His wife, Shazia, rushed him to the nearest hospital. It was full, but staffers checked his oxygen level: 62, dangerously low.

For three hours, they went from hospital to hospital trying to get him admitted, with no luck. She took him home. At 3:30 a.m., with Shahzad struggling to breathe, she called an ambulance. When the driver arrived, he asked if Shahzad truly needed oxygen — otherwise he would save it for the most serious patients.

The scene at the hospital was “harrowing,” said Shazia: a line of ambulances, people crying and pleading, a man barely breathing. Shahzad finally found a bed. Now Shazia and her two children, 8 and 6, have also developed covid-19 symptoms.

From early morning until late at night, Prafulla Gudadhe’s phone does not stop ringing. Each call is from a constituent and each call is the same: Can he help to arrange a hospital bed for a loved one?

Gudadhe is a municipal official in Nagpur, a city in the interior of Maharashtra. “We tell them we will try, but there are no beds,” he said. About 10 people in his ward have died at home in recent days after they couldn’t get admitted to hospitals, Gudadhe said, his voice weary. “I am helpless.”

Kamlesh Sailor knows how bad it is. Worse than the previous wave of the pandemic, like nothing he’s ever seen.

Sailor is the president of a crematorium trust in the city of Surat. Last week, the steel pipes in two of the facility’s six chimneys melted from constant use. Where the facility used to receive about 20 bodies a day, he said, now it is receiving 100.

“We try to control our emotions,” he said. “But it is unbearable.”

America’s nightmarish year is finally ending

One year after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the end of that pandemic is within reach.

The big picture: The death and suffering caused by the coronavirus have been much worse than many people expected a year ago — but the vaccines have been much better.

Flashback: “Bottom line, it’s going to get worse,” Anthony Fauci told a congressional panel on March 11, 2020, the day the WHO formally declared COVID-19 to be a global pandemic.

- A year ago today, the U.S. had confirmed 1,000 coronavirus infections. Now we’re approaching 30 million.

- In the earliest days of the pandemic, Americans were terrified by the White House’s projections — informed by well-respected modeling — that 100,000 to 240,000 Americans could die from the virus. That actual number now sits at just under 530,000.

- Many models at the time thought the virus would peak last May. It was nowhere close to its height by then. The deadliest month of the pandemic was January.

Yes, but: Last March, even the sunniest optimists didn’t expect the U.S. to have a vaccine by now.

- They certainly didn’t anticipate that over 300 million shots would already be in arms worldwide, and they didn’t think the eventual vaccines, whenever they arrived, would be anywhere near as effective as these shots turned out to be.

Where it stands: President Biden has said every American adult who wants a vaccine will be able to get one by the end of May, and the country is on track to meet that target.

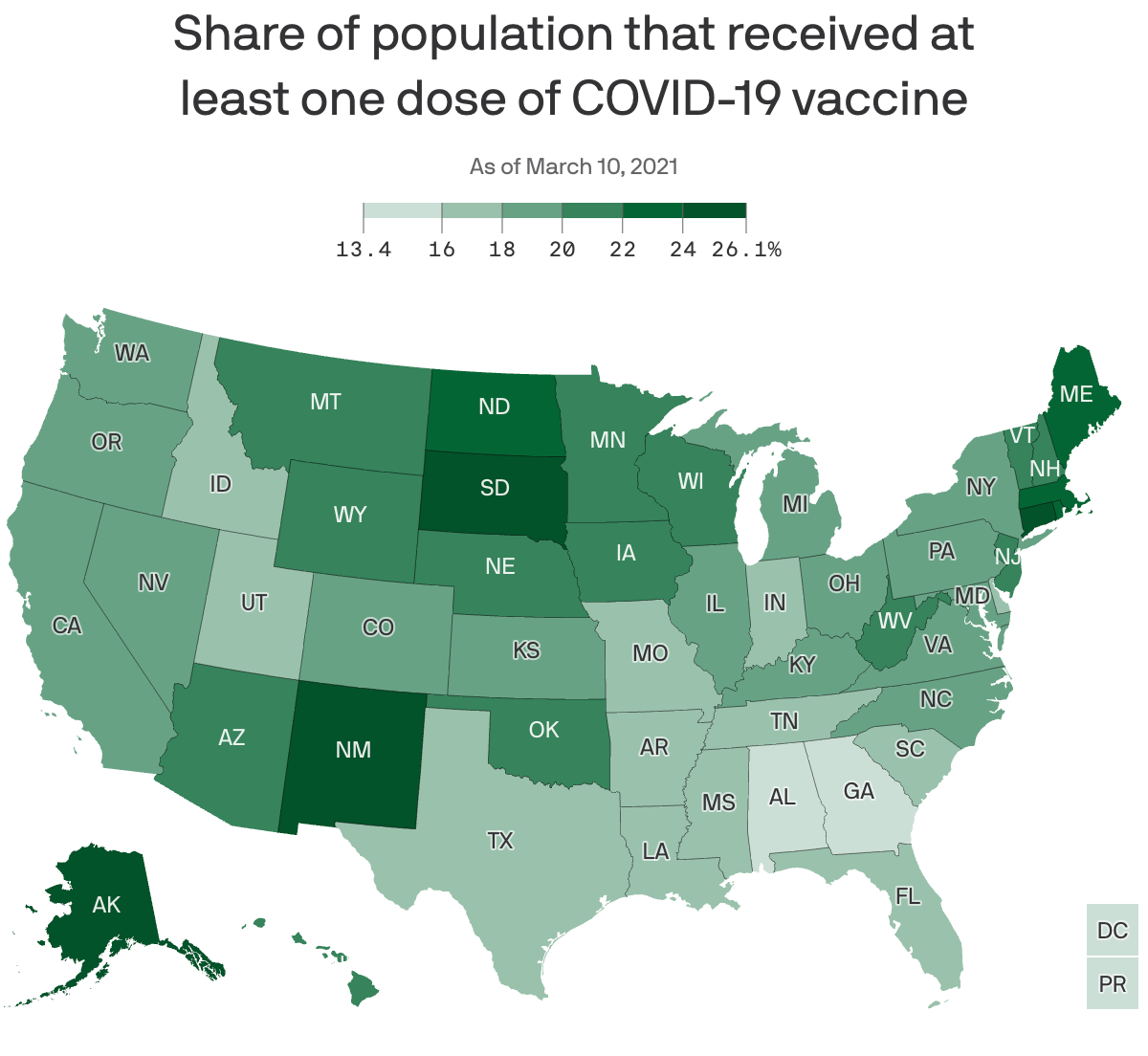

- The U.S. is administering over 2 million shots per day, on average. Roughly 25% of the adult population has gotten at least one shot.

- The federal government has purchased more doses than this country will be able to use: 300 million from Pfizer, 300 million from Moderna and 200 million from Johnson & Johnson.

- The Pfizer and Moderna orders alone would be more than enough to fully vaccinate every American adult. (The vaccines aren’t yet authorized for use in children.)

Yes, millions of Americans are still anxiously awaiting their first shot — and navigating signup websites that are often frustrating and awful.

- But the supply of available vaccines is expected to surge this month, and the companies say the bulk of those doses should be available by the end of May.

- Cases, hospitalizations and deaths are all falling sharply at the same time vaccinations are ramping up.

The bottom line: Measured in death, loss, isolation and financial ruin, one year has felt like an eternity. Measured as the time between the declaration of a pandemic and vaccinating 60 million Americans, one year is an instant.

- The virus hasn’t been defeated, and may never fully go away. Getting back to “normal” will be a moving target. Nothing’s over yet. But the end of the worst of it — the long, brutal nightmare of death and suffering — is getting close.

THE BIG DEAL—House passes $1.9T coronavirus relief bill

https://thehill.com/policy/finance/542448-heres-whats-in-the-19t-covid-19-relief-package

The House on Wednesday passed the mammoth $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package, which President Biden is expected to sign Friday.

The House approved the relief package in a starkly partisan 220-211 vote, sending the legislation to the White House and clinching Democrats’ first big legislative victory in the Biden era. No Republicans voted for the package and all but one House Democrat—Rep. Jared Golden of Maine—supported it. The Hill’s Cristina Marcos has more here.

The political split: Unlike the previous relief measures enacted last year, Democrats barely bothered to negotiate with Republicans and pushed the relief package through Congress along party lines using the budget reconciliation process. That allowed them to go as big as they wanted to go without running into a Senate GOP filibuster.

- Republicans argue the use of a process dodging the filibuster shows Biden wasn’t serious about bringing unity, and House GOP lawmakers on Wednesday warned of the bill’s total cost.

- But Democrats think Republicans will pay for their opposition to the popular bill and argued that they would oppose anything Biden proposed.

What’s in the $1.9T COVID-19 relief package: Along with $1,400 direct payments to households, an extension of expanded unemployment benefits, and aid for state and local governments, the package is loaded with other provisions intended to speed up the recovery from the recession and help struggling families fight the impact of COVID-19.

- Tax credits: The bill increases the child tax credit for households below certain income thresholds for 2021 and makes it fully refundable, and also expands the earned income tax credit for the year.

- Child care: $15 billion for grants to help low-income families afford child care and increases the child and dependent care tax credit for one year.

- Pensions: $86 billion to bailout struggling union pension funds.

- Transportation: $30 billion to bolster local subway and bus systems, $8 billion for airports, $1.5 billion for furloughed Amtrak workers, and $3 billion for wages at aerospace companies.

- Housing: $27.4 billion in emergency rental assistance, another $10 billion to help homeowners avoid foreclosure, $5 billion in vouchers for public housing, $5 billion to tackle homelessness and $5 billion more to help households cover utility bills.

- Small businesses: The American Rescue Plan broadens eligibility guidelines for the Paycheck Protection Program, allowing more nonprofit entities to be eligible, adds $15 billion in emergency grants and also sets aside more than $28 billion in funding for restaurants.

- ObamaCare subsidies and Medicaid expansion: The bill increases ObamaCare subsidies through 2022 to make them more generous, a longtime goal for Democrats, and opens up more fully subsidized plans to individuals. It also would provide extra Medicaid funding to states that expand the program and have yet to do so.

The Burdens Grow Heavier for COVID-19 Health Care Providers

Soon after the COVID-19 pandemic began last spring, Christine Choi, DO, a second-year medical resident at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, volunteered to enter COVID-19 patient rooms. Since then, she has worked countless nights in the intensive care unit in full protective gear, often tasked with giving the sickest patients and their families the grim choice between intubation or near-certain death.

“I’m offering this guy two terrible options, and that’s how I feel about work: I can’t fix this for you and it sucks, and I’m sorry that the choices I’m giving you are both terrible,” Choi told the Los Angeles Times’ Soumya Karlamangla about one patient encounter.

While Choi exhibits an “almost startlingly positive attitude” in her work, it’s no match for the psychological burdens placed on her shoulders by the global pandemic, Karlamangla wrote. When an older female COVID-19 patient died in the hospital recently, her husband — in the same hospital with the same diagnosis — soon began struggling to breathe. Sensing that he had little time left, Choi held a mobile phone at his bedside so that each of his children could come on screen to tell him they loved him. “I was just bawling in my [personal protective equipment],” Choi said. “The sound of the family members crying — I probably will never forget that,” she said.

It was not the first time the young doctor helped family members say goodbye to a loved one, and it would not be the last. Health care providers like Choi have had to work through unimaginable tragedies and unprecedented circumstances because of COVID-19, with little time to dedicate to their own mental health or well-being.

It has been nearly a year since the US reported what was believed at the time to be its first coronavirus death in Washington State. Since then, the pandemic death toll has mushroomed to nearly 500,000 nationwide, including 49,000 Californians. These numbers are shocking, and yet they do not capture the immeasurable emotional weight that falls on the health care providers with the most intimate view of COVID-19’s deadly progression. “The horror of the pandemic has unfolded largely outside public view and inside hospitals, piling a disproportionate share of the trauma on the people whose work takes them inside their walls,” Karlamangla wrote.

Experts are deeply concerned about the psychological and physical burdens that providers must bear, and the fact that there is still no end in sight. “At least with a natural disaster, it happens, people get scattered all over the place, property gets damaged or flooded, but then we begin to rebuild,” Lawrence Palinkas, PhD, MA, a medical anthropologist at USC, told Karlamangla. “We’re not there yet, and we don’t know when that will actually occur.”

Burned Out and Exhausted

A new CHCF survey of 1,202 California doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and behavioral health specialists confirms that levels of burnout and exhaustion are rising as the pandemic wears on. The survey, conducted January 4 to 14, 2021, is the second in a three-part series assessing COVID-19-related effects on health care providers.

Sixty-eight percent of providers said they feel emotionally drained from their work, 59% feel burned out, 57% feel overworked, and 50% feel frustrated. The poll asked providers who say they feel burned out what contributes most to that viewpoint. One doctor from the Central Valley wrote:

“Short staffed due to people out with COVID. I’m seeing three times as many patients, with no time to chart or catch up. Little appreciation or contact from my bosses. I have never had an N95 [mask]. The emotional toll this pandemic is taking. Being sick myself and spreading it to my wife and young kids. Still not fully recovered but needing to be at work due to physician shortages. Lack of professional growth, and a sense of lack of appreciation at work and feeling overworked. The sadness of the COVID-related deaths and the stories that go along with the disease. That’s a lot of stuff to unpack.”

Safety-net providers and health care workers with larger populations of patients of color are more likely to experience emotional hardships at work. As we know well by now, COVID-19 exacerbates the health disparities that have long burdened people of color and disproportionately harms communities with fewer health care and economic resources.

Women Bear the Brunt

The pandemic has been especially challenging for female health providers, who compose 77% of health care workers with direct patient contact. “The pandemic exacerbated gender inequities in formal and informal work, and in the distribution of home responsibilities, and increased the risk of unemployment and domestic violence,” an international group of experts wrote in the Lancet. “While trying to fulfill their professional responsibilities, women had to meet their families’ needs, including childcare, home schooling, care for older people, and home care.”

For one female doctor from the Bay Area who responded to the CHCF survey, the extra burdens of the pandemic have been unrelenting: “Having to work more, lack of safe, affordable, available childcare while I’m working. As a single mother, working 15 hours straight, then having to care for my daughter when I get home. Just exhausted with no days off. So many Zoom meetings all day long. Miss my family and friends.”

It is unclear how the pandemic will affect the health care workforce in the long term. For now, the damage “can be measured in part by a surge of early retirements and the desperation of community hospitals struggling to hire enough workers to keep their emergency rooms running,” Andrew Jacobs reported in the New York Times.

One of the early retirements Jacobs cited was Sheetal Khedkar Rao, MD, a 42-year-old internist in suburban Chicago. Last October, she decided to stop practicing medicine after “the emotional burden and moral injury became too much to bear,” she said. Two of the main factors driving her decision were a 30% pay cut to compensate for the decline in revenue from primary care visits and the need to spend more time at home after her two preteen children switched to remote learning.

“Everyone says doctors are heroes and they put us on a pedestal, but we also have kids and aging parents to worry about,” Rao said.

Working Through Unremitting Sickness and Death

In addition to the psychological burden, health care providers must cope with a harsh physical toll. People of color account for most COVID-19 cases and deaths among health care workers, according to a KFF issue brief. Some studies show that health care workers of color “are more likely to report reuse of or inadequate access to [personal protective equipment] and to work in clinical settings with greater exposure to patients with COVID-19.”

“Lost on the Frontline,” a collaboration of Kaiser Health News and the Guardian, has counted more than 3,400 deaths among US health care workers from COVID-19. Eighty-six percent of the workers who died were under age 60, and nurses accounted for roughly one-third of the deaths.

“Lost on the Frontline” provides the most comprehensive picture available of health care worker deaths, because the US still lacks a uniform system to collect COVID-19 morbidity and mortality data among health care workers. A year into the project, the federal government has decided to take action. Officials at the US Department of Health and Human Services cited the project when asking the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for a rapid expert consultation to understand the causes of deaths among health care workers during the pandemic.

The National Academies’ report, published December 10, recommends the “adoption and use of a uniform national framework for collecting, recording, and reporting mortality and morbidity data” along with the development of national reporting standards for a core set of morbidity impacts, including mental well-being and psychological effects related to working through public health crises. Some health care experts said the data gathering could be modeled on the federal government’s World Trade Center Health Program, which provides no-cost medical monitoring and treatment for workers who responded to the 9/11 terrorist attacks 20 years ago.

“We have a great obligation to people who put their lives on the line for the nation,” Victor J. Dzau, MD, president of the National Academy of Medicine, told Jacobs.

Why vaccine production is taking so long

COVID-19 vaccine makers are under intense pressure to rev up production, but the scale of the challenge is unprecedented — and the speed of production is limited.

Why it matters: Even with help from the federal government and outside companies, vaccine-making is a complex, time-consuming biological process. That limits how quickly companies like Pfizer and Moderna can accelerate their output even during a crisis.

The big picture: With new, more transmissible variants emerging, we’re in a race to get shots into more people’s arms. What would normally take years to set up is being compressed into less than a year, leaving engineers to adapt manufacturing processes on the fly.

- “The bottlenecks keeps moving. It keeps changing,” said Chaz Calitri, who leads the COVID-19 vaccine program at Pfizer’s Kalamazoo, Mich., facility.

- “It’s a dream project, but at the same time, it’s the weight of the world,” he tells Axios.

Between the lines: Making vaccines is complex, and the process can be hindered at different steps.

- “There’s a lot of science and engineering that goes into the manufacturing of any vaccine,” adds Margaret Ruesch, a vice president of Worldwide Research and Development at the company. “It’s molecular biology at a large scale.”

How it works: Axios got a deep dive into the making of Pfizer’s vaccine, a three-phase process that takes weeks from start to finish and involves three different facilities.

1) DNA manufacturing: At a plant near St. Louis, Mo., Pfizer produces DNA that encodes messenger RNA — instructions for cells to make part of the spike protein on the surface of the coronavirus. That primes the immune system to defend against future encounters with the virus.

- The DNA is produced by bacterial cells, then purified, frozen and shipped to another Pfizer facility in Andover, Mass.

2) Making the mRNA: In Andover, the template DNA is incubated with messenger RNA building blocks in a reactor to make the mRNA. Pfizer has been making two, 40-liter batches per week — up to 10 million doses worth —but expects to double that to four batches per week.

- After purification and quality checks, the frozen mRNA is shipped to a Pfizer plant in Kalamazoo, Mich.

3) Formulating the vaccine: In Kalamazoo, the mRNA and lipid nanoparticles (oily envelopes that deliver mRNA to cells in the body) are combined and go through a series of filtrations.

- The bulk vaccine is then transferred to sterile vials, capped, inspected, labeled and packed into containers the size of pizza boxes. Those containers are then stored in sub-zero freezers to await shipment to vaccine distribution sites.

Where it stands: Both Pfizer and Moderna say they’re on track to meet their commitments to deliver 200 million doses each to the U.S. over the first half of the year.

- The Biden administration yesterday announced it had secured deals for another 200 million doses, bringing the total to roughly 600 million doses, enough to fully vaccinate 300 million Americans by the end of July.

- Pfizer and its German partner BioNTech recently upped supplies 20% by getting FDA approval to squeeze a sixth dose (instead of five) out of every vial.

- Yes, but: Extracting a sixth dose requires the use of specialized syringes, which have their own production constraints, as Reuters explained.

The latest: The Biden administration said last week that it will use its wartime powers under the Defense Production Act to give Pfizer priority access to critical components such as filling pumps and filtration units to try to help address bottlenecks.

- Meanwhile, Pfizer continues to tweak its processes to boost output and says it is adding more suppliers and contract manufacturers to the vaccine supply chain.

- Novartis, Sanofi and Merck KGaA are among 10 contract manufacturers that will help the company manufacture more doses, a Pfizer spokesman tells Axios.

- Pfizer and BioNTech will still do most of the work in their facilities, but contract manufacturers will help with specific tasks like formulating lipid nanoparticles, sterile filling, inspection and packaging.

Ordering other drug manufacturers to stand up manufacturing lines to whip up extra batches of Pfizer’s or Moderna’s vaccines is not an efficient or practical way for the federal government to quickly increase supplies, some experts say.

- “Making vaccines is not like making cars, and quality control is paramount,” Stanley Plotkin, a vaccine industry consultant, told Kaiser Health News. “We are expecting other vaccines in a matter of weeks, so it might be faster to bring them into use.”

What to watch: Johnson & Johnson has requested emergency use authorization from the FDA for its single-dose vaccine, but is reportedly lagging in production, the NYT first reported last month.

Where the pandemic has been deadliest

In the seven states hit hardest by the pandemic, more than 1 in every 500 residents have died from the coronavirus.

Why it matters: The staggering death toll speaks to America’s failure to control the virus.

Details: In New Jersey, which has the highest death rate in the nation, 1 out of every 406 residents has died from the virus. In neighboring New York, 1 out of every 437 people has died.

- In Mississippi, 1 out of every 477 people has died. And in South Dakota, which was slammed in the fall, 1 of every 489 people has died.

States in the middle of the pack have seen a death rate of around 1 in 800 dead.

- California, which has generally suffered severe regional outbreaks that don’t span the entire state, has a death rate of 1 in 899.

- Vermont had the lowest death rate, at 1 of every 3,436 residents.

The bottom line: Americans will keep dying as vaccinations ramp up, and more transmissible variants of the coronavirus could cause the outbreak to get worse before it gets better.

- Experts also say it’s time to start preparing for the next pandemic — which could be deadlier.