Clinician burnout, lay-offs, and other healthcare workforce challenges coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic are creating issues for primary care, according to a new survey.

About 40 percent of over 700 primary care clinicians recently surveyed by the Larry A. Green Center, Primary Care Collaborative (PCC), and 3rd Conversation worry that primary care won’t exist in five years’ time. Meanwhile, about a fifth say they expect to leave primary care within the next three years.

“Primary care is the front door to the healthcare system for most Americans, and the door is coming off its hinges,” Christine Bechtel, co-founder of 3rd Conversation, a community of patients and clinicians, said in a press release. “The fact that 40 [percent] of clinicians are worried about the future of primary care is of deep concern, and it’s time for new public policies that value primary care for the common good that it is.”

The threat to primary care comes as practices ramp up vaccination efforts. The survey found that more than half of respondents (52 percent) report receiving enough or more than enough vaccines for their patients, and 31 percent are partnering with local organizations or government to prioritize people for vaccination.

Stress levels at primary care practices are also decreasing compared to the height of the pandemic, according to survey results. However, over one in three, or 36 percent, of respondents say they are experiencing hardships, such as feeling constantly lethargic, having trouble finding joy in anything, and/or struggling to maintain clear thinking.

Clinician fatigue could spell trouble for the primary care workforce and the field itself, researchers indicated.

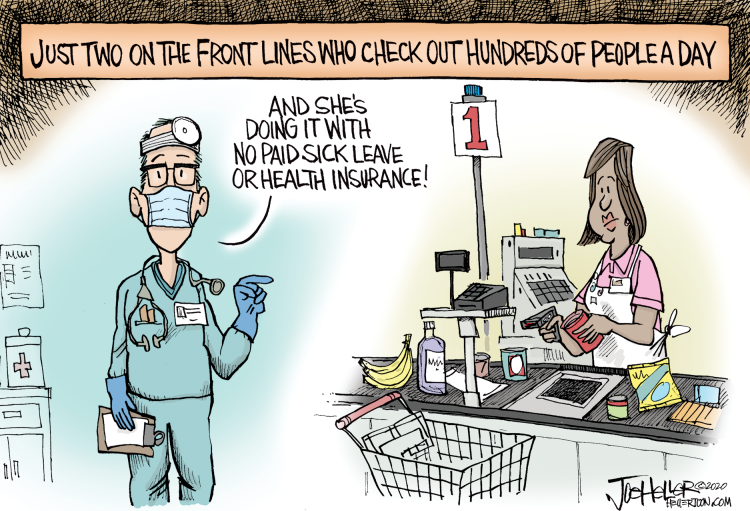

“The administration has now recognized the key role primary care is able to play in reaching vaccination goals,” Rebecca Etz, PhD, co-director of The Larry A. Green Center, said in the release. “While the pressure is now on primary care to convert the most vaccine-hesitant, little has been done to support primary care to date. Policymakers need to bear witness to the quiet heroism of primary care – a workforce that suffered five times more COVID-related deaths than any other medical discipline.”

Many primary care clinicians are hoping the federal government steps in to change policy and bolster primary care and the healthcare workforce. The government can start with how primary care is paid, respondents agreed.

About 46 percent of clinicians responding to the survey said policy should change how primary care is financed so that the field is not in direct competition with specialty care. The same percentage of clinicians also said policy to change how primary care is paid by shifting reimbursement from fee-for-service.

Over half of clinicians (56 percent) also agreed that policy should protect primary care as a common good and make it available to all regardless of ability to pay.

Alternative payment models helped providers during the COVID-19 pandemic, research from healthcare improvement company Premier, Inc. showed. Their study found that organizations in alternative payment models were more likely to leverage care management, remote patient monitoring, and population health data during the pandemic compared to organizations that relied on fee-for-service revenue.

“Many of the practices, especially in primary care, have been extremely cash strapped and have been struggling for many years,” Sanjay Doddamani, MD, told RevCycleIntelligence last year.

“This has been a big moment for us to act in accelerating our performance-based incentive payments to our primary care doctors. We moved up our schedule of payments so that they could at least have some continued flow of funds,” added the chief physician executive and COO at Southwestern Health Resources, a clinically integrated network based in Texas.

Value-based contracting could be the key to primary care’s existence in the future, that is, if practices get on board with alternative payment models. A majority of respondents to the latest Value-Based Care Assessment from Insights said over 75 percent of their organization’s revenue is from fee-for-service contracts. This was especially true for respondents working in physician practices, of which 64 percent relied almost entirely on fee-for-service payments.