Last week, I made my once a decade trek to a dealership to buy a new car. I did my research in advance (and even negotiated the price) so I was hoping for a stress-free experience.

It was – up until the point where I got locked in the finance manager’s office for “the talk”. You know, the one where you are made to feel like a neglectful parent unless you pony up for all the fixin’s – everything from nitrogen filled tires to paint protection (just in case I encounter a flock of migratory geese on the drive home). I shook my head no about ten times before we got to the pre-paid maintenance plan options. I decided to be polite and listen (plus I was curious since I was purchasing a car from a manufacturer notorious for costly repairs). As compelling as it was to pay nearly $5,000 to what ultimately would amount to a few tire rotations for my electric vehicle, I held firm. The finance manager angrily handed me my signed documents and whisked me out of his office.

I guess I can’t blame car dealers for applying massive mark-ups for services that are inexpensive to provide. Except similar financial chicanery is currently playing out in our health insurance system. If you swap out the finance manager for a health insurer and replace me with the average everyday consumer, the dealer’s tactics are analogous to how insurers game medical loss ratio (MLR) requirements (except as a health care consumer, you can’t say “no”).

A bit of background is in order to understand why I thought about health insurance and car dealers in the same breath.

Insurance companies are required to spend a certain percentage of money they get from premiums on medical costs and quality improvement (QI); this is known as the medical loss ratio (MLR). If companies do not meet this ratio (usually 80-85%, depending on the product), they must refund the difference in the form of a rebate, or reduction in future premiums, to consumers.

Like any for-profit corporation in America today, a health insurer wants to avoid giving money back to consumers. Therefore, insurers have become adept at manipulating their MLRs through various accounting and financial engineering techniques. This manipulation optimizes their ability to meet MLR thresholds and avoid paying rebates, which runs afoul of its intended purpose: to ensure that patients receive the appropriate level of care.

So how do insurers game the system, and what evidence exists for this activity?

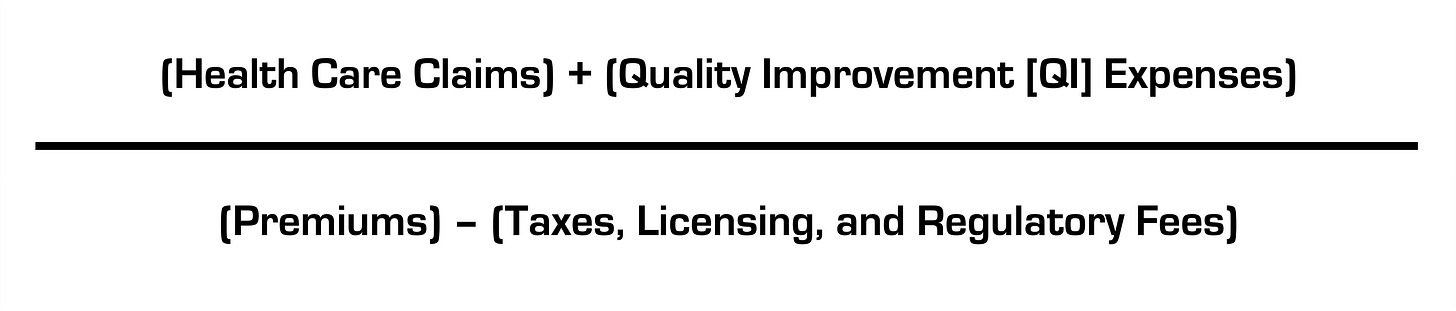

The current MLR formula is:

Health insurers do not control taxes and fees, but they can easily engineer the other variables. Below, I’ll explain how.

Step 1: Quality Improvement (QI) Expenses

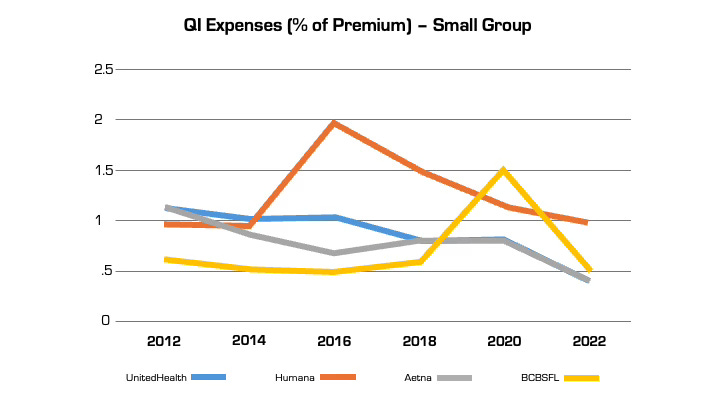

The definition of allowable QI expenses is broad and includes activities to improve outcomes, patient safety, and reduce mortality (mom and apple pie stuff). Insurers played a big role in writing the MLR regulations after Congress enacted legislation and made sure they’d have wide latitude in what expenses are classified as QI (akin to the car dealer “option” list) and what product segments they assign them to.

Looking at reported QI expenses sheds light on this practice. QI expenses vary between insurers. But they also vary widely for the same insurer from year to year (even after controlling for geography and product segment). In large part, this is attributable to financial engineering. QI costs can be effectively “transferred” on the income statement from one product segment to another, by adjusting the pro rata weightings). This enables them to optimize MLR performance across their insurance portfolio (i.e. by taking from a bucket with excess medical costs and putting it in another with insufficient costs) in a way that maximizes benefit to the insurer and is camouflaged from regulators and consumers. This is language from a recent UnitedHealth Group filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission: “Assets and liabilities jointly used are assigned to each reportable segment using estimates of pro-rata usage.”

Although these QI percentages are small, the associated dollar amounts are large. In 2022, UnitedHealth, Humana, and Aetna reported $494 million, $550 million, and $395 million respectively in allowable QI expenses for their national plans. While there is some legitimate QI activity at insurers (e.g., pharmacists who identify high risk medications in the elderly), the reality is that much of the QI work is already heavily resourced within provider organizations, where it is more effective. Insurers also can (and do) count “wellness and health promotion activities” despite limited evidence these programs improve health outcomes and are more often used by insurers as marketing tools.

Step 2. Health Care Claims

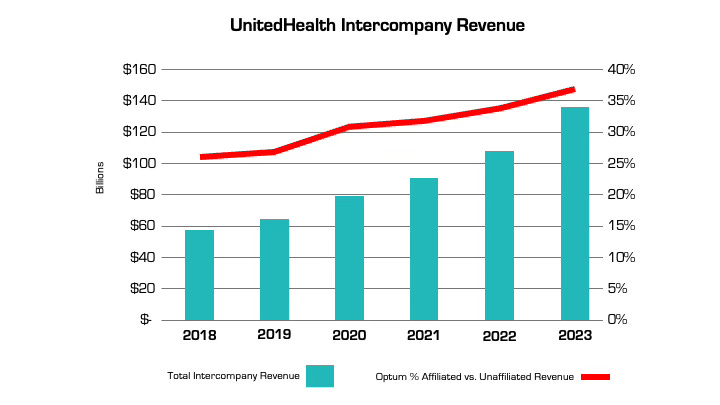

The other variable that insurers can manipulate is claims costs. The more an insurer is vertically integrated, the easier it is. The prime example is UnitedHealth, which has an insurance arm (UnitedHealthcare) and a big division that encompasses medical services, among many other things (Optum), as well as various other subsidiaries. Optum Health and Optum Rx receive a significant portion of their revenue from UnitedHealthcare for providing services like care and pharmacy benefit management to people enrolled in its health plans. In fact, the amount of UnitedHealth’s corporate “eliminations,” (meaning inter-company revenue that is reported on their consolidated financial statement) has more than doubled over the past five years (from $58.5 billion to $136.4 billion). The proportion of revenue Optum derives from UnitedHealthcare versus unaffiliated entities has increased by nearly 50% over the same period. A similar trend is playing out at every major insurer.

Take the example of the insurance company Aetna, the PBM CVS Caremark, and CVS Pharmacy, which are all vertically integrated and owned by CVS Health. If a patient goes to a CVS store to fill a prescription for Imatinib, a generic chemotherapy drug, the total cost the patient and insurance company pay is $17,710.21 for a 30-day supply. The same drug is sold by Cost Plus Drugs for $72.20 (the cost is calculated by adding the wholesale price and a 15% fee). When the patient fills the prescription at a CVS retail pharmacy, CVS Health can record that the patient paid a medical claim cost of $17,710.21 (even though the cost to acquire the drug is $70) and the remaining $17,640 can be retained as profits disguised as medical costs.

Insurers’ extensive acquisition of physician practices also facilitates gamification of the MLR via its ability to pay capitation (a set amount per person) to a risk-bearing provider organization (RBO) it owns, such as a medical group. This enables the insurer to lock in a set amount of premium as “medical expense” (usually around 85%) with the downstream provider group “managing” those costs. There’s a loophole, however. While the insurer has technically met its MLR requirement, the downstream RBO is subject to far fewer regulations on how it spends the money, which makes it easier to generate profits by skimping on care.

The regulations on RBOs vary by state. In many cases, while RBOs need to meet minimum capital requirements, they are not subject to the same MLR provisions as insurers. For a vertically integrated insurer that gets a huge amount of revenue from taxpayer-supported programs like Medicare Advantage and Medicaid, this essentially means that (1) the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services puts the money into the insurer’s right pocket, (2) the insurer moves it to the left pocket, and (3) CMS checks the right pocket – and just the right pocket – at the end of the year to make sure it’s mostly empty (without regard to the fact that the left one may be busting at the seams).

The good news is there are ways to address these issues, both through updating the MLR provisions in the Affordable Care Act (which are long in the tooth) and more rigorous and comprehensive reporting requirements and regulation of vertically integrated insurers.

Just like I don’t want car dealers pushing unnecessary add-ons to increase their profit margins, consumers deserve that the required portion of their hard spent premium dollar actually goes toward their health care instead of further enriching huge corporations, executives, and Wall Street shareholders.