In a world where change is the only constant, the swift currents of modern life contrast starkly with the sluggish pace of genetic evolution—and of American healthcare, too.

Two relatively recent scientific discoveries demonstrate how the very genetic traits that once secured humanity’s survival are failing to keep up with the times, producing dire medical consequences. These important biological events offer insights into American medicine—along with a warning about what can happen when healthcare systems fail to change.

The Mysteries Of Sickle Cell And Multiple Sclerosis

For decades, scientists were baffled by what seemed like an evolutionary contradiction.

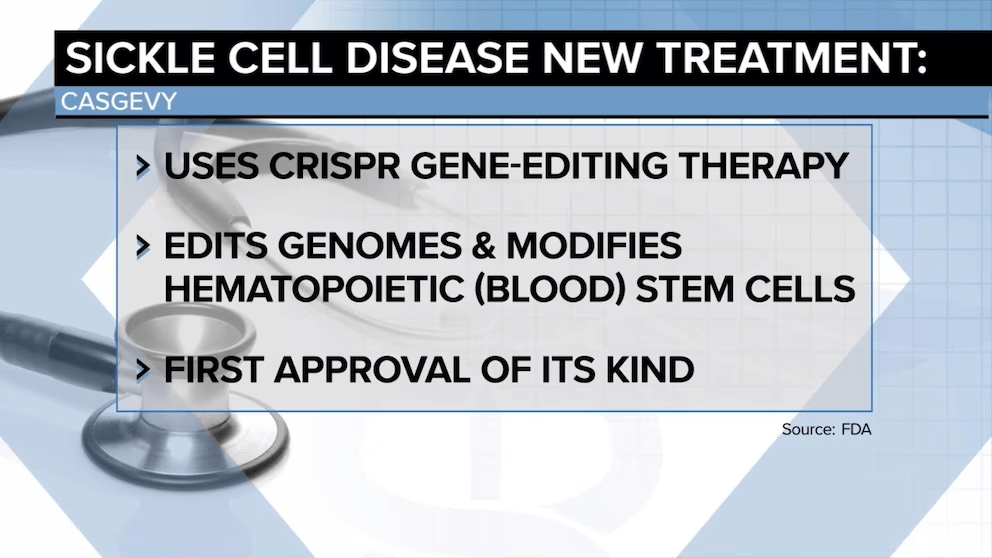

Sickle cell disease is a condition resulting from a genetic mutation that produces malformed red blood cells. It afflicts approximately 1 in 365 Black Americans, causing severe pain and organ failure.

Its horrific impact on people raises a question: How has this genetic mutation persisted for 7,300 years? Nature is a merciless editor of life, and so you would expect that across seven millennia, people with this inherited problem would be less likely to survive and reproduce. This curiosity seems to defy the teachings of Charles Darwin, who theorized that evolution discards what no longer serves the survival of a species.

Scientists solved this genetic puzzle in 2011, illuminating a significant evolutionary trade-off.

People living with sickle cell disease have two abnormal genes, one inherited from each parent. While the disease, itself, affects a large population (roughly 100,000 African Americans), it turns out that a far larger population in the United States carries one “abnormal” gene and one normal gene (comprising as many as 3 million Americans).

This so called “sickle cell trait” presents milder symptoms or none at all when compared to the full disease. And, unlike those with the disease, individuals who with one (but not both) abnormal genes possess a distinct evolutionary advantage: They have a resistance to severe malaria, which every year claims more than 600,000 lives around the globe.

This genetic adaptation (a resistance to malaria) kept people alive for many millennia in equatorial Africa, protecting them from the continent’s deadliest infectious disease. But in present-day America, malaria is not a major public-health concern due to several factors, including the widespread use of window screens and air conditioning, controlled and limited habitats for the Anopheles mosquitoes (which transmit the disease), and a strong healthcare system capable of managing and containing outbreaks. Therefore, the sickle cell trait is of little value in the United States while sickle cell disease is a life-threatening problem.

The lesson: Genetic changes beneficial in one environment, such as malaria-prone areas, can become harmful in another. This lesson isn’t limited to sickle cell disease.

A similar genetic phenomenon was uncovered through research that was published last month in Nature. This time, scientists discovered an ancient genetic mutation that is, today, linked to multiple sclerosis (MS).

Their research began with data showing that people living in Northern Europe have twice the number of cases of MS per 100,000 individuals as people in the South of Europe. Like sickle cell disease, MS is a terrible affliction—with immune cells attacking neurons in the brain, interfering with both walking and talking.

Having identified this two-fold variance in the prevalence of MS, scientists compared the genetic make-up of the people in Europe with MS versus those without this devastating problem. And they discovered a correlation between a specific mutated gene and the risk of developing MS. Using archeological material, the researchers then connected the introduction of this gene into Northern Europe with cattle, goat and sheep herders from Russia who migrated west as far back as 5,000 years ago.

Suddenly, the explanation comes into focus. Thousands of years ago, this genetic abnormality helped protect herders from livestock disease, which at the time was the greatest threat to their survival. However, in the modern era, this same mutation results in an overactive immune response, leading to the development of MS.

Once again, a trait that was positive in a specific environmental and historical context has become harmful in today’s world.

Evolving Healthcare: Lessons From Our Genes

Just as genetic traits can shift from beneficial to detrimental with changing circumstances, healthcare practices that were once lifesaving can become problematic as medical capabilities advance and societal needs evolve.

Fee-for-service (FFS) payments, the most prevalent reimbursement model in American healthcare, offer an example. Under FFS, insurance providers, the government or patients themselves pay doctors and hospitals for each individual service they provide, such as consultations, tests, and treatments—regardless of the value these services may or may not add.

In the 1930s, this “mutation” emerged as a solution to the Great Depression. Organizations like Blue Cross began providing health insurance, ensuring healthcare affordability for struggling Americans in need of hospitalization while guaranteeing appropriate compensation for medical providers.

FFS, which linked payments to the quantity of care delivered, proved beneficial when the problems physicians treated were acute, one-time issues (e.g., appendicitis, trauma, pneumonia) and relatively inexpensive to resolve.

Today, the widespread prevalence of chronic diseases in 6 out of 10 Americans underlines the limitations of the fee-for-service (FFS) model. In contrast to “pay for value” models, FFS, with its “pay for volume” approach, fails to prioritize preventive services, the avoidance of chronic disease complications, or the elimination of redundant treatments through coordinated, team-based care. This leads to increased healthcare costs without corresponding improvements in quality.

This situation is reminiscent of the evolutionary narrative surrounding genetic mutations like sickle cell disease and MS. These mutations, which provided protective benefits in the past, have become detrimental in the present. Similarly, healthcare systems must adapt to the evolving medical and societal landscape to better meet current needs.

Research demonstrates that it takes 17 years on average for a proven innovation in healthcare to become common practice. When it comes to evolution of healthcare delivery and financing, the pace of change is even more glacial.

In 1934, the Committee on the Cost of Medical Care (CCMC) concluded that better clinical outcomes would be achieved if doctors (a) worked in groups rather than as fragmented solo practices and (b) were paid based on the value they provided, rather than just the volume of work they did.

Nearly a century later, these improvements remain elusive. Well-led medical groups remain the minority of all practices while fee-for-service is still the dominant healthcare reimbursed method.

Things progress slowly in the biological sphere because chance is what initiates change. It takes a long time for evolution to catch up to new environments.

But change in healthcare doesn’t have to be random or painfully slow. Humans have a unique ability to anticipate challenges and proactively implement solutions. Healthcare, unlike biology, can advance rapidly in response to new medical knowledge and societal needs. We have the opportunity to leverage our knowledge, technology, and collaborative skills to address and adapt to change much faster than random genetic mutations. But it isn’t happening.

Standing in the way is a combination of fear (of the risks involved), culture (the norms doctors learn in training) and lack of leadership (the ability to translate vision into action).

Genetics teaches us that evolution ultimately triumphs. Mutations that save lives and improve health become dominant in nature over time. And when those adaptations no longer serve a useful purpose, they’re replaced.

I hope the leaders of American medicine will learn to adapt, embracing the power of collaborative medicine while replacing fee-for-service payments with capitation (a single annual payment to group of clinicians to provide the medical care for a population of patients.) If they wait too long, dinosaurs will provide them with the next set of biological lessons.