Category Archives: Healthcare Economics

CVSHealth Eyes Breakup: A Reckoning for Corporate Health Care’s Vertical Empire

In a surprising turn of events, sources say that CVS Health is exploring the possibility of breaking up its business empire — a move that could unravel years of aggressive vertical integration, including its $70 billion acquisition of health insurer Aetna back in 2017.

While details are still slim, such a move signals just how dire the situation has become for CVSHealth as it navigates mounting financial and regulatory pressures on multiple fronts.

It’s yet another chapter in a story that has seen CVSHealth evolve from a retail pharmacy chain into a health care behemoth — but perhaps one that grew too big, too fast. And to be honest, I’m not surprised. I’ve seen this movie before. In fact, I saw it many times – although each time with different stars – during my 20 years in the health insurance business. One of the most memorable featured Aetna, which in the late 1990s and early 2000s had to retrench, at Wall Street’s insistence, after a buying spree of smaller health insurers that brought the company a ton of unprofitable accounts and disappointing bottom lines. Aetna followed its buying spree with a purging spree, dumping as many as eight million health plan enrollees in short order to get back into Wall Street’s good graces.

It seems that CVSHealth also bought too much too fast. The results? Rising expenses, frustrated patients, and now potential cracks in the corporate structure itself.

CVS: A Cautionary Tale of Vertical Integration

Large corporations like CVS and its peers have used their size to dominate various aspects of health care—whether it’s insurance, retail pharmacy, physician practices and clinics, and controlling the drug supply chain. But as these mega-corporations continue to grow, they also become harder to manage, and their inefficiencies start to become evident.

CVS’s acquisition of Aetna was hailed at the time as a strategic masterstroke — a way to streamline health care by bringing together the different parts of the system under one corporate umbrella. It was supposed to deliver “efficiencies” that would benefit both the company and patients.

But it’s not just the purchase of Aetna. From pharmacy benefit manager Caremark to Aetna to health care providers Signify Health and Oak Street Health — CVS’s business model has become increasingly complex, making it difficult to navigate regulatory scrutiny, rising costs and fierce competition in the retail pharmacy space.

The latest reports suggest that CVS’s board is trying to figure out where Caremark would land in the event of a breakup. Would it stay with the retail side or with the insurance arm?

This isn’t just an internal debate; it’s emblematic of the broader issue—CVS has built a vertically integrated structure that was supposed to work together to improve care, but investors are now questioning how and even if these pieces should fit together.

It’s Been a Hard Few Years for CVS

Federal Trade Commission’s Legal Action Against CVS’s Caremark and Other PBMs

Instead, those supposed efficiencies have largely translated into higher costs for consumers and increased scrutiny from regulators, especially with CVS’s Caremark at the center of anti-competitive practices allegations by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). PBMs like Caremark control the drug pricing landscape in ways that lack transparency and disproportionately affect patients and independent pharmacies.

Now, as CVS grapples with rising medical costs within its Aetna business — just like its biggest competitors, UnitedHealth and Humana —the company’s management appears to be in damage control mode. While nothing is certain, discussions about splitting the business have reached the boardroom level, according to sources familiar with the matter. This comes as activist investors, like Glenview Capital, push for structural changes to improve CVS’s declining financial performance.

CVS’s Aetna Medicare Advantage Loss in New York City

New York City Mayor Eric Adams had a plan to force city municipal retirees out of traditional Medicare and into a corporate Aetna Medicare Advantage plan. The NYC Organization of Public Service Retirees vehemently opposed the move and spent months fighting it.

In August, a Manhattan Supreme Court judge permanently halted the mayor and Aetna’s attempts.

Wall Street Woes

For CVS Health, 2024 started off bad. CVS missed Wall Street financial analyst’s earnings-per-share expectations for the first quarter of 2024 by several cents. Shareholders’ furor sent CVS’ stock price tumbling from $67.71 to a 15-year low of $54 at one point.

An astonishing 65.7 million shares of CVS stock were traded that day. The company’s sin: paying too many claims for seniors and people with disabilities enrolled in its Medicare Advantage plans.

Also in August, CVS Health cut its 2024 forecast for a third time, citing troubles covering seniors via the company’s private Medicare Advantage business. Operating income for CVS Health’s insurance arm, Aetna, dropped a whopping 39% in Q3, which forced the company to shake up its leadership – moving CEO Karen Lynch into the role of managing insurance and publicly firing one of her lieutenants, Executive Vice President Brian Kane.

What’s Next?

The notion that CVS could split its operations would effectively unwind one of the most high-profile health care mergers in recent memory. A split up of the company would mark the end of an era in which health care conglomerates could grow unchecked. CVS’s struggle isn’t happening in isolation—other companies, like Walgreens and Rite Aid, are facing similar financial difficulties and structural questions.

CVS’s potential breakup could signal a broader industry trend toward unwinding massive, vertically integrated health care corporations.

Whether CVS breaks up or not, it’s clear that the model of health care mega-mergers, designed to consolidate power and increase corporate profits, is facing serious headwinds. Cigna recently announced that it is getting out of the Medicare Advantage business and Humana is getting out of the commercial insurance market. UnitedHealth, meanwhile, so far seems to be weathering those headwinds, but it, too, will be facing even more scrutiny by lawmakers and regulators in the months and years ahead.

The hospital finance misconception plaguing C-suites

Health systems have a big challenge: rising costs and reimbursement that doesn’t keep up with inflation. The amount spent on healthcare annually continues to rise while outcomes aren’t meaningfully better.

Some people outside of the industry wonder: Why doesn’t healthcare just act more like other businesses?

“There seems to be a widely held belief that healthcare providers respond the same as all other businesses that face rising costs,” said Cliff Megerian, MD, CEO of University Hospitals in Cleveland. “That is absolutely not true. Unlike other businesses, hospitals and health systems cannot simply adjust prices in response to inflation due to pre-negotiated rates and government mandated pay structures. Instead, we are continually innovating approaches to population health, efficiency and cost management, ensuring that we maintain delivery of high quality care to our patients.”

Nonprofit hospitals are also responsible for serving all patients regardless of ability to pay, and University Hospitals is among the health systems distinguished as a best regional hospital for equitable access to care by U.S. News & World Report.

“This commitment necessitates additional efforts to ensure equitable access to healthcare services, which inherently also changes our payer mix by design,” said Dr. Megerian. “Serving an under-resourced patient base, including a significant number of Medicaid, underinsured and uninsured individuals, requires us to balance financial constraints with our ethical obligations to provide the highest quality care to everyone.”

Hospitals need adequate reimbursement to continue providing services while also staffing the hospital appropriately. Many hospitals and health systems have been in tense negotiations with insurers in the last 24 months for increased pay rates to cover rising costs.

“Without appropriate adjustments, nonprofit healthcare providers may struggle to maintain the high standards of care that patients deserve, especially when serving vulnerable populations,” said Dr. Megerian. “Ensuring fair reimbursement rates supports our nonprofit industry’s aim to deliver equitable, high quality healthcare to all while preserving the integrity of our health systems.”

Industry outsiders often seek free market dynamics in healthcare as the “fix” for an expensive and complicated system. But leaving healthcare up to the normal ebbs and flows of businesses would exclude a large portion of the population from services. Competition may lead to service cuts and hospital closures as well, which devastates communities.

“A misconception is that the marketplace and utilization of competitive business model will fix all that ails the American healthcare system,”

said Scot Nygaard, MD, COO of Lee Health in Ft. Myers and Cape Coral, Fla.

“Is healthcare really a marketplace, in which the forces of competition will solve for many of the complex problems we face, such as healthcare disparities, cost effective care, more uniform and predictive quality and safety outcomes, mental health access, professional caregiver workforce supply?”

Without comprehensive reform at the state or federal level, many health systems have been left to make small changes hoping to yield different results. But, Dr. Nygaard said, the “evidence year after year suggests that this approach is not successful and yet we fear major reform despite the outcomes.”

The dearth of outside companies trying to enter the healthcare space hasn’t helped. People now expect healthcare providers to function like Amazon or Walmart without understanding the unique complexities of the industry.

“Unlike retail, healthcare involves navigating intricate regulations, providing deeply personal patient interactions and building sustained trust,” said Andreia de Lima, MD, chief medical officer of Cayuga Health System in Ithaca, N.Y. “Even giants like Walmart found it challenging to make primary care profitable due to high operating costs and complex reimbursement systems. Success in healthcare requires more than efficiency; it demands a deep understanding of patient care, ethical standards and the unpredictable nature of human health.”

So what can be done?

Tracea Saraliev, a board member for Dominican Hospital Santa Cruz (Calif.) and PIH Health said leaders need to increase efforts to simplify and improve healthcare economics.

“Despite increased ownership of healthcare by consumers, the economics of healthcare remain largely misunderstood,” said Ms. Saraliev. “For example, consumers erroneously believe that they always pay less for care with health insurance. However, a patient can pay more for healthcare with insurance than without as a result of the negotiated arrangements hospitals have with insurance companies and the deductibles of their policy.”

There is also a variation in cost based on the provider, and even with financial transparency it’s a challenge to provide an accurate assessment for the cost of care before services. Global pricing and other value-based care methods streamline the price, but healthcare providers need great data to benefit from the arrangements.

Based on payer mix, geographic location and contracted reimbursement rates, some health systems are able to thrive while others struggle to stay afloat. The variation mystifies some people outside of the industry.

“Healthcare economics very much remains paradoxical to even the most savvy of consumers,” said Ms. Saraliev.

November 2022 Health Sector Economic Indicators Briefs

https://altarum.org/publications/november-2022-health-sector-economic-indicators-briefs

Economic Indicators | November 18, 2022

Altarum’s monthly Health Sector Economic Indicators (HSEI) briefs analyze the most recent data available on health sector spending, prices, employment, and utilization. Support for this work is provided by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Below are highlights from the November 2022 briefs.

Health spending growth continues to lag GDP growth

- National health spending in September 2022 grew by 4.4%, year over year.

- Health spending in September 2022 is estimated to account for 17.4% of GDP, essentially identical to the August 2022 value, which was the lowest share since June 2015.

- Nominal GDP in September 2022 was 8.9% higher than in September 2021 as GDP growth continues to outpace health spending growth.

- The health spending share of GDP has declined from a recent high of 18.5% of GDP in December 2021, largely because of high economy-wide inflation.

Health care price growth remains moderate amid slowing economywide inflation

- The Health Care Price Index (HCPI) increased by 2.9% year over year in October, up slightly from 2.8% a month earlier.

- Economywide price growth slowed this month, as overall CPI inflation fell to 7.7% and PPI price growth fell to 8.0%. Services CPI growth (excluding health care) held steady at 7.0% year over year, while commodities inflation fell for a fourth straight month to 8.6%.

- Among the major health care categories, price growth for dental care (5.4%), nursing home care (4.2%), and hospital services (3.5%) were above average, while physician services (0.3%) and prescription drug (2.2%) price growth were the slowest growing categories.

- Growth in our implicit measure of utilization for September was the slowest it has been in 2022, down to 1.8% year-over-year growth from 2.2% a month prior in August.

Health care job growth remains strong while health care wage growth moderates

- Health care job growth remained strong in October, with 52,600 jobs added. Health care has averaged 47,000 new jobs per month in 2022.

- Most of the growth in health care jobs was in ambulatory care, which added 30,700 jobs in October. Hospitals added 10,800 jobs and nursing and residential care added 11,100 jobs.

- The economy added 261,000 jobs in October, similar to August and September gains. The unemployment rate rose slightly to 3.7%.

- Health care wage growth appears to be moderating. After peaking at 7.4% growth year over year in July, health care wages grew by 5.6% in September, nearer to economy-wide wage growth of 5.0%.

- Wage growth fell across all three major health care settings: residential care wages grew at 7.7% compared to a peak of 11% in March 2022, hospital wages grew by 5.8% compared to a peak of 8.5% in June, and ambulatory care wages grew by 4.6% compared to a peak of 5.8% in July.

The US Healthcare Market Debate, Explained Through Economics

Everyone agrees that the US healthcare system is not working so great. Compared to the rest of the world, our healthcare is extremely expensive and yet we suffer worse health by many measures. And we can’t seem to agree on what’s to blame, or what we should do about it. Do we have too much, or not enough, competition? Should the government intervene in health care markets more or less?

Basic economics can help us better understand what’s happening.

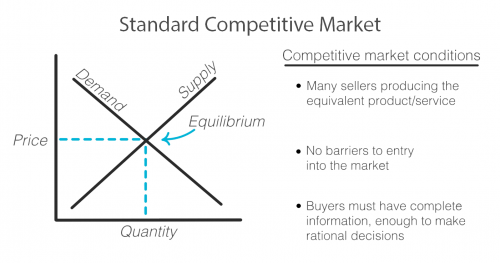

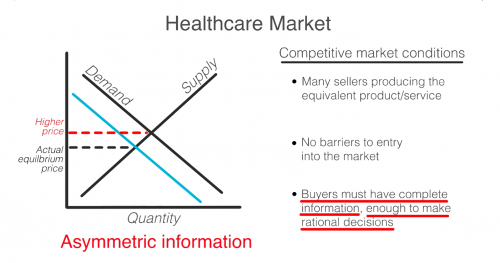

As with any exchange of goods and services, the standard competitive market model has the familiar upward sloping supply curve and downward sloping demand curve, illustrating that when prices are higher, demand decreases and supply increases as sellers are incentivized to produce more of that good or service at its higher price. Sellers and buyers arrive at what quantity to produce and consume and at what price based on where these two lines intersect, called the equilibrium. Both buyer and seller are happy with the deal they’ve struck!

But not every market works this way. There are actually standards that need to be met in order for a market to fit this model and for it to work efficiently for both the buyer and seller.

First, there must exist multiple sellers competing to sell the same goods or services and new sellers must be able to easily enter the market.

There must be a sufficient open exchange of information between buyer and seller about price, availability, and value of a service or good.

And buyers must make, or be in a position to make, rational decisions using the information they possess about the market.

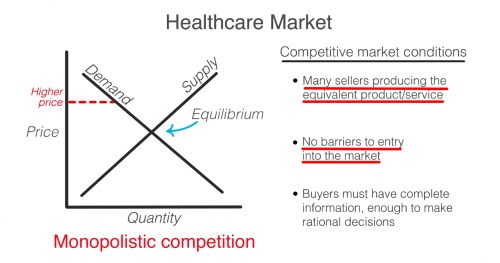

Healthcare does not meet these standards and when these standards are not met, the equilibrium cannot be reached or accurately known. Any price and quantity that falls outside of the equilibrium is considered a market failure. Using only this model, we can see how healthcare’s market failures contribute to high prices.

To start, it’s true that healthcare is failing the market standards when it comes to competition. The number of sellers in the market is decreasing due to both an increase in barriers to entry and due to consolidation, including hospital mergers. This causes an imbalance in power of the seller over the buyer that can begin to reflect what economists call monopolistic competition where sellers can charge a price above the perfect competition equilibrium. In the extreme, when there is only one seller, the market is a monopoly.

So then, don’t we just need more competition? Unfortunately, a lack of competition isn’t the only reason that healthcare fails the market standards.

Another failure is that consumers in healthcare, patients, do not have all the information that providers, like doctors and hospitals, do. This is known as asymmetric information. Patients often have no idea before getting care how much it will cost, what the prices available to them elsewhere are, or what the quality will be. When consumers are in the dark about these basic features, the true demand and supply will be different than the model. The true demand may be lower if patients knew ahead of time how much it cost or how much less valuable the service is compared to how it is promoted. This means prices can be set higher than they likely would be if the true demand was known.

Even if patients had full information, they are not always in a position to act as rational consumers. A patient’s decision may be influenced by their concern for their health, or their ability to think rationally may itself be affected by their condition.

So, as you can see, the problem is that a lack of competition only accounts for part of the reason why healthcare doesn’t meet the market standards. No matter how much the government either steps back to allow for more competition or invests to foster competition, the market will never fix ALL of these failures on its own. Healthcare is not and can never be a free market. It simply does not fit this model.

In 1963, economist and later Nobel prize winner, Kenneth Arrow, warned us about this looming healthcare crisis. He explains that “If the actual market differs significantly from the competitive model […] coordination of purchases and sales must take place”

That coordination he is referring to is government intervention.

Dr. Mike Chernew, Health Economist and Professor of Health Policy at Harvard Medical School agrees…“an unregulated health care market is unlikely to lead to desired outcomes.”

In reality, health care always has, and always will, involve a combination of both government intervention and market forces to control prices and increase quality. The debate isn’t really whether or not the government should intervene, but by how much and in what way.