The website for the group Physicians for Informed Consent (PIC) reads like an apolitical, educational resource that provides information on vaccines and why they shouldn’t be government-mandated. Its mission is “that doctors and the public are able to evaluate the data on infectious diseases and vaccines objectively, and voluntarily engage in informed decision-making about vaccination.”

The group’s accompanying social media accounts, however, tell a different story. On PIC’s Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn feeds, you’ll find post after post about reasons to be scared of vaccines – especially for children – often highlighting selective portions of scientific research that contain vaccination risks.

Who’s Behind PIC?

The group was founded in 2015 after California passed a law that prohibited the use of personal belief exemptions from vaccinations required for children to attend any public or private school in the state.

Three years later, the number of waivers issued by doctors to parents seeking medical exemptions for their children tripled. As a result, another law was passed in 2019, cracking down on the inappropriate use of medical exemptions.

The group’s founder, Shira Miller, MD, is a concierge integrative medicine doctor based in Los Angeles, specializing in menopausal care. On her own Twitter profile, she describes herself as “Facebook’s Most Popular Menopause Doctor.”

Miller earned her medical degree in 2002 from Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel, and has reportedly been working as a concierge physician since 2010.

PIC’s leadership team also includes 20 physicians from a wide range of specialties, most of whom, like Miller, don’t specialize in infectious diseases.

Among its leaders is Paul Thomas, MD, an Oregon-based pediatrician. Thomas, who is listed as one of PIC’s founding directors, was issued an emergency suspension order of his medical license in 2021 by the state medical board, in which they cited at least eight cases of alleged patient harm. In line with PIC’s philosophy, Thomas maintains that he isn’t “anti-vax” – he’s pro-informed-consent.

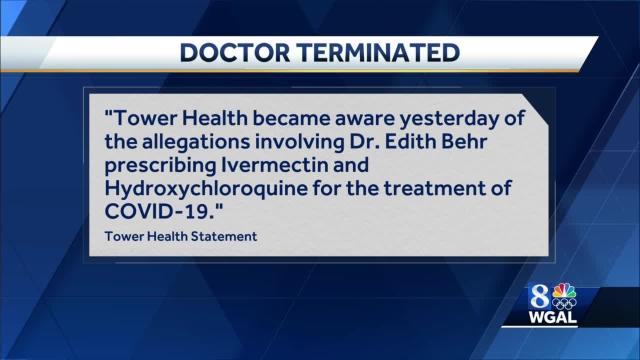

Also on the team is Jane Orient, MD, internist and executive director of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS), a group that also opposes vaccine mandates. Orient received her medical degree from Columbia University and currently practices in Arizona. In 2020, the AAPS sued the federal government for withholding its stockpile of hydroxychloroquine from COVID patients, despite research showing that the drug is ineffective. The complaint was dismissed in September 2021.

Doug Mackenzie, MD, a plastic surgeon who graduated from Johns Hopkins University of Medicine, is PIC’s treasurer. He has previously identified himself as an “ex-vaxxer” rather than an anti-vaxxer when speaking on a panel in 2019.

The only RN on the team is Tawny Buettner. After California mandated vaccinations for healthcare workers, Buettner organized a protest outside of her place of work, Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego; she later sued the hospital after she was dismissed from her job. According to the complaint, Buettner and the 36 other plaintiffs alleged that their requests for religious exemptions from the COVID-19 vaccine were all denied.

Kenneth Stoller, MD, also listed on the leadership team, graduated from the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine and completed pediatric residency training at the University of California Los Angeles. Stoller was disciplined in 2019 for doling out medical exemptions to children without adequate evidence. According to state records, his license in California has since been revoked; he currently holds a medical license in New Mexico.

What’s PIC?

The most notable physician groups accused of spreading COVID-19 misinformation since the vaccine rollout have been affiliated with right-wing media, if not overtly proclaiming conservative, anti-vaccination beliefs.

For example, America’s Frontline Doctors, a group notorious for its support of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19, has made its values well-known. The group’s founder, Simone Gold, MD, JD, was arrested for participating in the Jan. 6 capitol riot and has openly opposed mask-wearing. Similarly, physician leaders of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, known for promoting the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19, tout their appearances on the ultra-conservative Newsmax on the website’s homepage.

PIC wants to be different. The group’s focus, according to its general counsel Greg Glaser, JD, of Copperopolis, California, is on the “authoritative citations that show, or calculate, the risks [of vaccines] to the public,” he told MedPage Today.

“We are pro-informed consent, pro-ethics, pro-health. PIC is not anti-vaccine, and PIC is not pro-vaccine – PIC is neutral,” Glaser said on behalf of the group.

In August 2021, Glaser submitted an amicus brief to the Supreme Court PIC’s behalf, arguing against the implementation of vaccine mandates. The document claims that “government statements confirm there is no evidence that COVID-19 vaccines prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19,” ignoring the breadth of existing literature that says otherwise.