https://www.cbsnews.com/news/jobs-report-may-inflation-interest-rates/

The US labor market added more jobs than expected in May defying previous signs of a slowdown in the economy.

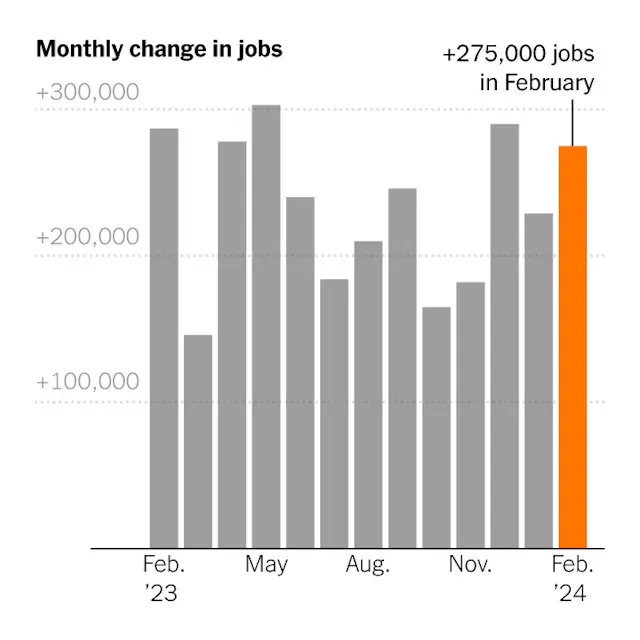

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics released Friday showed the labor market added 272,000 nonfarm payroll jobs in May, significantly more additions than the 180,000 expected by economists.

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate rose to 4% from 3.9% the month prior. May’s job additions came in significantly higher than the 165,000 jobs added in April.

The print highlights the difficulty the Federal Reserve faces in determining when to lower interest rates and how quickly. The economy and labor market has held up overall, and inflation has remained sticky, building the case for holding rates higher for longer. Yet some cracks have emerged, such as signs of inflation pressuring lower income consumers and rising household debt.

“They’re really walking a tight rope here,” Robert Sockin, Citi senior global economist, told Yahoo Finance of the central bank. He noted the longer the Fed holds rates steady, the more cracks could develop in the economy.

Wages, considered an important metric for inflation pressures, increased 4.1% year over year, reversing a downward trend in year-over-year growth from the month prior. On a monthly basis, wages increased 0.4%, an increase from the previous month’s 0.2% gain.

“To see more confidence that inflation could move lower over time, you’d really like to see the wage numbers look a little lower than we’ve seen them today,” Lauren Goodwin, New York Life Investments economist and chief market strategist, told Yahoo Finance.

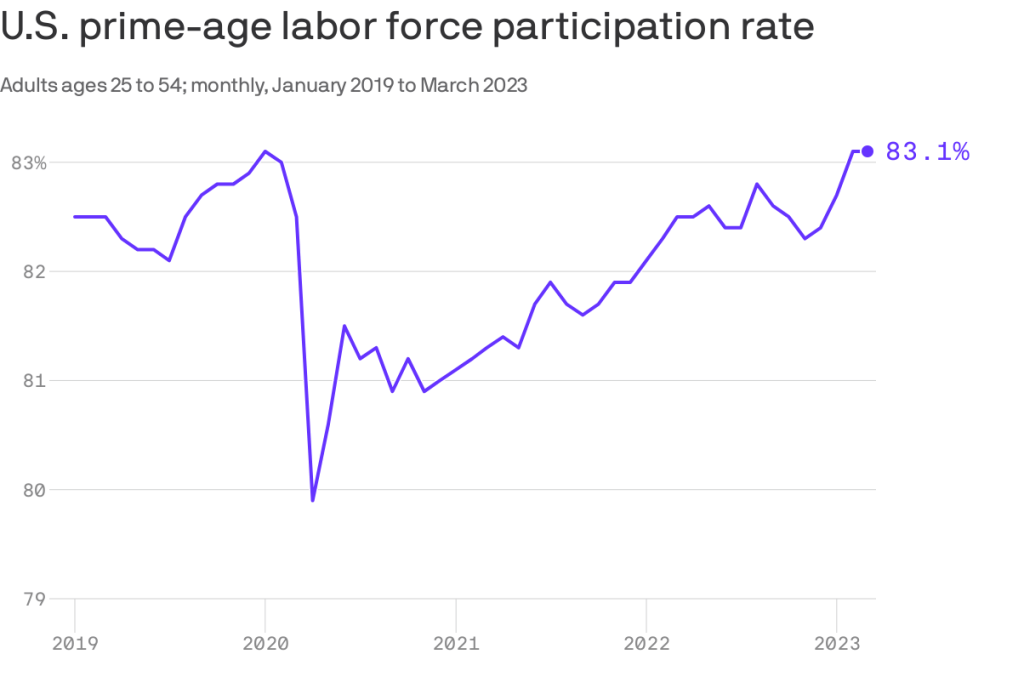

Also in Friday’s report, the labor force participation rate slipped to 62.5% from 62.7% the month prior. However, participation among prime-age workers, ages 25-54, rose to 83.6%, its highest level in 22 years.

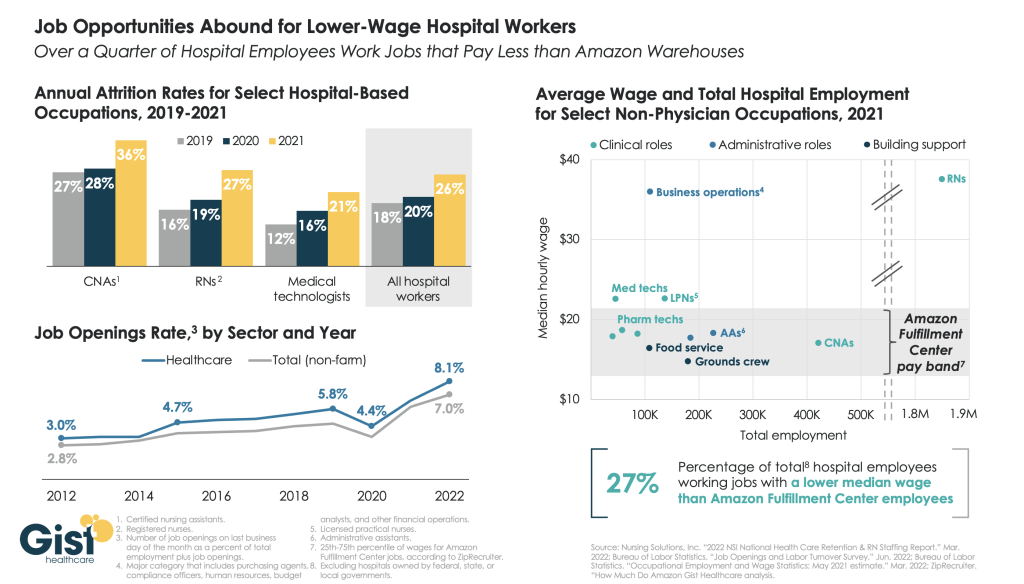

The largest jobs increases in Friday’s report were seen in healthcare, which added 68,000 jobs in. May. Meanwhile, government employment added 43,000 jobs. Leisure and hospitality added 42,000 jobs.

The report comes as the stock market has hit record highs amid a slew of softer-than-expected economic data, which had increased investor confidence that the Federal Reserve could cut interest rates as of September. After Friday’s labor report, that trend reversed with investors pricing in a 53% chance the Fed cuts rates in September, down from a roughly 69% chance seen just a day prior, per the CME FedWatch Tool.

Other data out this week has reflected a still-resilient labor market that’s showing further signs of normalizing to pre-pandemic levels. The latest Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), released Tuesday, showed job openings fell in April to their lowest level since February 2021.

Notably, the ratio between the number of job openings and unemployed people returned to 1.2 in May, which is in line with pre-pandemic levels.