Yesterday, a three-judge panel from the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s individual mandate. The judges agreed with a lower court decision issued in the case, Texas v. U.S., in December 2018 that the individual mandate is unconstitutional but, unlike the lower court, did not decide that the rest of the ACA is also unconstitutional. Instead, the judges remanded, or sent back, the decision to the same lower court judge to consider. California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, who is leading the 21 Democratic state attorneys general defending the law, along with the U.S. House of Representatives, immediately announced he would appeal the decision to the Supreme Court.

Whether the Supreme Court will decide to take the case now or wait for the decision of Judge O’Connor’s, of the lower court, is uncertain. If the Court decides to take the case now, they could expedite the briefing process and issue a decision in 2020. If it does not take the case now, a ruling will be delayed until after the 2020 presidential election.

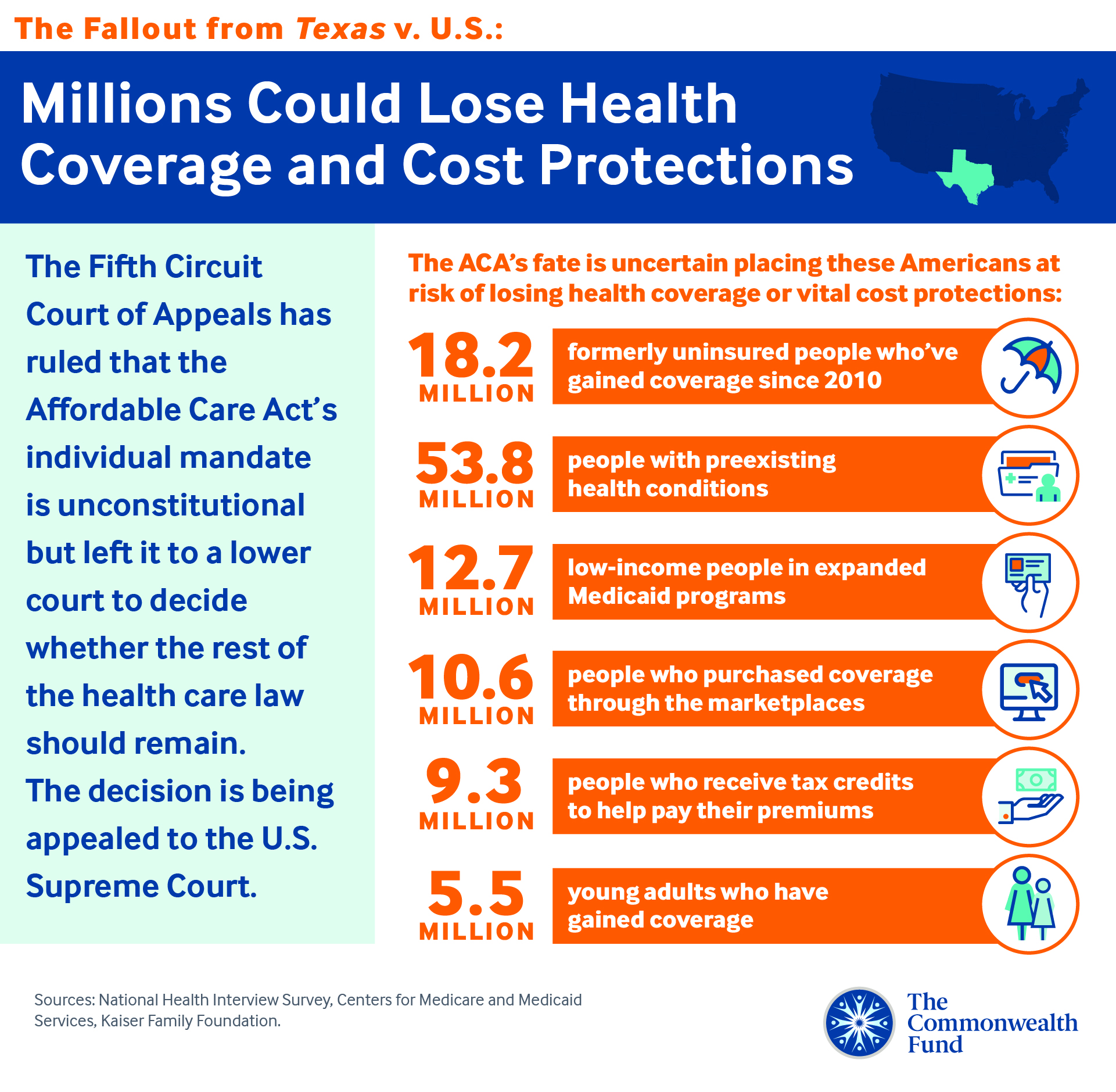

No one knows how the Supreme Court will ultimately rule. But we do know that if the Court decides to strike down the ACA, the human toll will be immense and tragic. The law has granted unprecedented health security to millions:

- 18.2 million formerly uninsured people have gained coverage since 2010

- 53.8 million Americans with preexisting health conditions are now protected

- 12.7 million low-income people are insured through expanded Medicaid

- 10.6 million people have coverage through the ACA marketplaces, 9.3 million of whom receive tax credits to help them pay their premiums

- 5.5 million young adults have gained coverage, many by staying on their parents’ plans

- 45 million Medicare beneficiaries have much better drug coverage.

Such a decision will also trigger massive disruption throughout the U.S. health system. The health care industry represents nearly 20 percent of the nation’s economy; the ACA has touched every corner of it. The law restructured the individual and small-group health insurance markets, expanded and streamlined the Medicaid program, improved Medicare benefits, and reformed the way Medicare pays doctors, hospitals, and other providers. It was a catalyst for the movement toward value-based care and established a regulatory pathway for biosimilars — less expensive versions of biologic drugs. States have rewritten laws to incorporate the ACA’s provisions. Insurers, hospitals, physicians, and state and local governments have invested billions of dollars in adjusting to these changes.

The law’s popular preexisting health condition protections have made it possible for people with minor-to-serious health problems to apply for coverage in the same way healthier people have always done. These protections have given the estimated 53.8 million Americans with preexisting health conditions the peace of mind that they will never be denied health insurance because of their health.

More than 150 million people who get coverage through their employers now are eligible for free preventive care, and their children can stay on their policies to age 26.

The wide racial and income inequities in health insurance coverage that have been partly remedied by the ACA would return. Hospitals and providers, especially safety-net institutions, would struggle with mounting uncompensated care burdens and sicker and more costly patients who are not receiving the preventive care they need.

The ACA tore down financial barriers to health care for millions, many of whom were uninsured for most of their lives. It has demonstrably helped people get the health care they need in states across the country. Research indicates that Medicaid expansion has led to improved health status and lower mortality risk.

To date, neither the Trump administration, which has sided with the plaintiffs in the case, nor its Republican colleagues in Congress have offered a replacement plan in the event the law is struck down. The historic progress made by Americans, particularly those with middle and lower incomes and people of color, could unravel. Voters are already telling policymakers they are worried about their ability to afford health care. Yesterday’s decision and the uncertain path forward to the Supreme Court is certain to escalate those worries. With the nation entering the 2020 presidential election year, the Supreme Court may decide to take up the case this term.