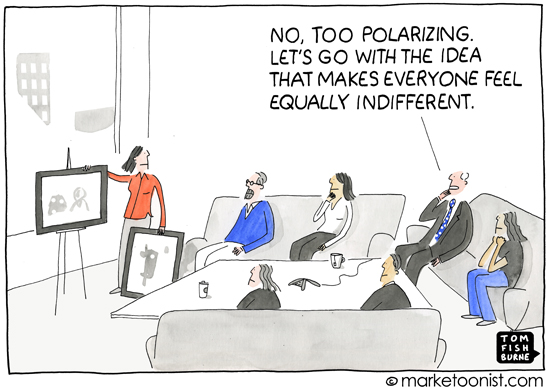

Cartoon – Our Wild Expectations

CMS ended its provider agreement with Blackfoot-based Idaho Doctors’ Hospital July 20.

Under rules enacted last September, a healthcare facility must average at least two inpatients per day and an at least two-night average length of stay to be considered an inpatient hospital for Medicare reimbursement. In April, CMS determined Doctors’ Hospital is not primarily engaged in providing care to inpatients and does not meet the new federal requirements for Medicare participation. The agency subsequently sent Doctors’ Hospital a Medicare termination notice.

“To go from being OK just 18 months ago, when we had our last survey, to now being told that we don’t meet the CMS conditions of participation because of new interpretations of the regulations is just difficult to comprehend,” Dave Lowry, administrative manager at Idaho Doctors’ Hospital, told KIFI earlier this month. “Like any business that is regulated by government agencies, we fully expect there to be changes to rules and their interpretations, but this drastic level of change just goes to show how much uncertainty there is in healthcare right now.”

After receiving the termination notice from CMS, Doctors’ Hospital sent letters to all patients affected by the contract termination, a spokesperson told Becker’s Hospital Review.

“We have worked with other area hospitals who provide the same services, and our staff provides this information for any patients who call with questions on where to go for care,” the Doctors’ Hospital spokesperson said.

United Nurses and Allied Professionals Local 5098, the union representing 2,400 workers at Rhode Island Hospital and Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, is encouraging members to apply for unemployment during a lockout, according to WPRI.

The workers, which include nurses, technicians and therapists, began a three-day strike about 3 p.m. July 23. They were willing to return to work at 3 p.m. July 26. However, Lifespan said it will not allow the workers to return until July 27 because of a commitment to temporary staff hired during the walkout.

Norman Farias, RN, executive vice president of UNAP Local 5098, told WPRI the union is encouraging workers to apply for unemployment for the 24 hours ending at 3 p.m. July 27 “because this is a day they would be working, and the hospital’s telling them they can’t.”

It is unknown whether workers’ claims will be approved by the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training.

According to hospital officials, the union was notified about the hospitals’ four-day commitment to temporary staff on July 13.

Franklin, Tenn.-based Community Health Systems, which operates 119 hospitals, saw its net loss shrink in the second quarter of 2018 as the company continues to refine its hospital portfolio.

CHS said revenues dipped to $3.56 billion in the second quarter of 2018, down 14 percent from $4.14 billion in the same period of the year prior. The decline was largely attributable to CHS operating 24 fewer hospitals in the second quarter of 2018 than in the same period of 2017. On a same-hospital basis, revenues climbed 3.3 percent year over year.

After factoring in operating expenses and one-time charges, CHS ended the second quarter of 2018 with a net loss attributable to stockholders of $110 million. That’s compared to the second quarter of 2017, when the company recorded a net loss of $137 million.

“Our second quarter results reflect progress in our key areas of strategic focus, most notably improvements in same-store operating results, progress on divestitures and successful refinancings,” said CHS Chairman and CEO Wayne T. Smith in an earnings release.

As part of a turnaround plan put into place in 2016, CHS announced plans in 2017 to sell off 30 hospitals. The company completed the divestiture plan Nov. 1. To further reduce its debt, CHS intends to sell another group of hospitals with combined revenues of $2 billion. The company has already made progress toward that goal.

During 2018, CHS has completed seven hospital divestitures and entered into definitive agreements to sell five others. CHS said it continues to receive interest from potential buyers for certain hospitals.

“As we complete additional divestitures this year, we believe our portfolio will become stronger, and more of our resources can be directed to markets where we have the greatest opportunities to drive incremental growth,” Mr. Smith said.

CHS’ long-term debt totaled $13.67 billion as of June 30, a decrease from $13.88 billion as of the end of last year.

Just what duty, if any, exists for doctors to keep tabs on their sickest patients?

“Will you be my regular doctor?” a new patient seeing me in my primary care clinic asked.

“Sort of,” I honestly answered.

She looked back at me quizzically.

“Technically speaking I will be your doctor,” I explained. “But you may have trouble scheduling an appointment with me and may have to see another doctor here at our group clinic at times. And if you need to get admitted to this hospital, other doctors who work there will take care of you.”

The patient seemed disappointed.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “But I’ll do my best to be available for you.”

It was not long ago that such words, coming from a doctor, would have been almost heretical. But logistical and philosophical changes in medicine have dramatically altered the doctor-patient relationship.

In clinic-based practices such as mine, patients may be told they may need to wait weeks or months in order to see their doctor. In the world of private medicine, some physicians now charge their patients extra annual fees for the privilege of seeing or speaking with their doctor more promptly.

Just how bad is this situation? Do patients followed by just one doctor do better or worse? And just what duty, if any, exists for doctors to keep tabs on their sickest patients?

My father, an infectious diseases specialist who practiced medicine from the 1950s to the 1990s, would have answered these questions: “Very bad,” “worse” and “a tremendous duty.” My dad was constantly vigilant, going to the hospital seven days a week, giving patients our home phone number and staying in touch with covering physicians when we were on vacation.

But things were different then. For one thing, it was expected that my father would follow his patients both in and out of the hospital. Today there are hospitalists — specialists in inpatient medicine who are in charge of admitted patients and specially trained to diagnose and treat illnesses requiring hospitalization. And my mother, like most doctors’ wives of a generation ago, did not expect my dad to be a co-parent. Medicine, after all, was a calling.

The reasons for the changes are diverse. For one thing, the growing number of women in medicine has helped bring a better work-life balance among physicians. In addition, the 1984 Libby Zion case, in which a young woman died while under the care of young doctors working 36-hour shifts, pointed out the potential dangers of sleep-deprived providers.

When I was a medical resident in the 1980s, the first “night floats”— doctors who covered the wards at night so other physicians could sleep or go home — appeared. To many doctors of my father’s era, this development was heresy. Medicine, they feared, was becoming “shift work.” Patients were passed from doctor to doctor, none of whom really “knew” them. With the advent of hospitalists, this fragmentation has gotten worse.

Fortunately, researchers are studying how well patients do in these competing types of systems. The 2016 FIRST trial, which received a lot of attention, found that patient safety was not compromised when doctors in training worked longer shifts.

But even when the data show that limiting work hours leads to as good or better care, physicians should not be content to play “doctor tag,” in which a physician or clinic simply designates a new provider to “take over” treatment. Just because a physician takes good care of someone during his or her shift does not mean that responsibility ends there.

It may be helpful to think about specialties within medicine that have long been associated with limited continuity, such as emergency or intensive-care medicine. In both of these venues, patients move in and out of treatment quickly and follow-up may be difficult. But it is not impossible.

In her new book, “You Can Stop Humming Now,” Dr. Daniela Lamas, a critical care specialist, recounts visits she made to patients after they had left her unit. In one case, she attends a party thrown by a man whose severe West Nile virus infection had initially made it unlikely he would ever return home. But now there he was, eating, chatting, “working the crowd” and reminding his son to videotape the event.

Dr. Lamas did this on her own time. But she found it immensely rewarding. “We rarely have the opportunity,” she writes, to follow patients “through long-term acute care hospitals, infections, delirium, readmissions, and maybe, if they are very lucky, back home to a life that looks something like what they left.” The patient and his wife seemed thrilled that she had come — not as his current doctor but as his past doctor who still cared.

And what of my patients? I have made a decision not to try to imitate my father, as much as I admire the type of doctor that he was. But patients deserve to have a “doctor,” despite the caveat to my new patient. Plus I have found that most physicians, at the end of the day, are control freaks, wanting to be in charge of their own patients.

So I try to stay in touch, by phone, computer or other messaging strategies. Patient portals, being implemented at many hospitals, now allow patients to leave messages for their physicians in secure ways that do not threaten confidentiality. And I “sneak in” patients with urgent issues when I am not scheduled in clinic but there are open rooms, such as early in the morning or during lunch. The generous staff members at my clinic help make this happen by registering these patients and getting their vital signs. My clinic is also pursuing strategies to increase the chance that patients can see their regular doctors.

My patients seem pleased when I go the extra mile. If I am willing to squeeze them in, they are willing to move around their schedules to come. But I just can’t promise I can or will always be available.

https://apnews.com/a69f5ada0db24ada9bc5bd8a44604f3b

The Trump administration’s Medicare chief on Wednesday slammed Sen. Bernie Sanders’ call for a national health plan, saying “Medicare for All” would undermine care for seniors and become “Medicare for None.”

The broadside from Medicare and Medicaid administrator Seema Verma came in a San Francisco speech that coincides with a focus on health care in contentious midterm congressional elections.

Sanders, a Vermont independent, fired back at Trump’s Medicare chief in a statement that chastised her for trying to “throw” millions of people off their health insurance during the administration’s failed effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Verma’s made her comments toward the end of a lengthy speech before the Commonwealth Club of California, during which she delved into arcane details of Medicare payment policies.

Denouncing what she called the “drumbeat” for “government-run socialized health care,” Verma said “Medicare for All” would “only serve to hurt and divert focus from seniors.”

“You are giving the government complete control over decisions pertaining to your care, or whether you receive care at all,” she added.

“In essence, Medicare for All would become Medicare for None,” she said. Verma also said she disapproved of efforts in California to set up a state-run health care system, which would require her agency’s blessing.

In his response, Sanders said that “Medicare is, by far, the most cost-effective, efficient and popular health care program in America.

He added: “Medicare has worked extremely well for our nation’s seniors and will work equally well for all Americans.”

The Sanders proposal would add benefits for Medicare beneficiaries, coverage for eyeglasses, most dental care, and hearing aids. It would also eliminate deductibles and copayments that Medicare and private insurance plans currently require.

Independent analyses of the Sanders plan have focused on the enormous tax increases that would be needed to finance it, not on concern about any potential harm to seniors currently enrolled in Medicare.

But so-called “Mediscare” tactics have been an effective political tool for both parties in recent years, dating back to Republican Sarah Palin’s widely debunked “death panels” to fan opposition to President Barack Obama’s health care overhaul. Democrats returned the favor after Republicans won control of the House in 2010 and tried to promote a Medicare privatization plan.

Democrats clearly believe supporting “Medicare for All” will give them an edge in this year’s midterm elections.

More than 60 House Democrats recently launched a “Medicare for All” caucus, trying to tap activists’ fervor for universal health care that helped propel Sanders’ unexpectedly strong challenge to Hillary Clinton for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination. Just a few years ago, Sanders could not find co-sponsors for his legislation.

A survey earlier this year by the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Washington Post found that 51 percent of Americans would support a national health plan, while 43 percent opposed it. Nearly 3 out of 4 Democrats backed the idea, as did 54 percent of independents. But only 16 percent of Republicans supported the Sanders approach.

Early in his career as a political figure, President Donald Trump spoke approvingly of Canada’s single-payer health care system, roughly analogous to Sanders’ approach. But by the 2016 presidential campaign Trump had long abandoned that view.