Cartoon – Modern Eye Exam

In Segment 2, we looked at the history of medical care in the U.S. until 1965, the year Congress enacted Medicare and Medicaid.

In Segment 3 we will look at reform movements, starting with Medicare and Medicaid. We will look at why later reforms failed and where that leaves us now.

By the early 1960s, nearly all employees were covered by Blue Cross/Blue Shield.

But problems emerged. First, low-wage workers were often not covered by their small businesses, and elderly retirees were not covered. Costs were going up because pre-paid insurance increased patient demand for services. Harry Truman had proposed national health insurance after he surprisingly was re-elected in 1948. But the AMA launched a multi-million-dollar publicity campaign to deride the plan as “Communism” and “socialized medicine.” Truman’s public insurance plan failed.

The next attempt at reform was successful – the 1965 passage of Medicare and Medicaid. Lyndon Johnson succeeded because coverage targeted the uninsured poor-and- elderly, leaving the rest of the private for-profit health system unaffected.

Senator Teddy Kennedy tried in 1971 to extend Johnson’s success to build a single-payer system, and won support from President Nixon. But this plan was derailed by the Watergate scandal.

The next attempt came from Bill and Hillary Clinton. After Clinton took office in 1992, Hillary and expert panels devised a plan for universal coverage including essential benefits and pre-existing conditions with mandated employer insurance and expanded Medicaid. This plan failed because the insurance industry launched a stinging publicity campaign featuring a down-home couple named “Harry and Louise.” Americans also balked at the tax increases needed to fund it.

The Clinton’s failure made it necessary to find another solution to rising costs. Managed care, which had first appeared in 1973, became that solution. And it did work, slowing growth to under 6%. But around the year 2000 came a backlash over mammograms and so-called “drive-by” deliveries, which undermined the ability of managed care to control costs.

What do we make of this history? Here are the main take-aways that help us understand our present health system. First, there has always been a tension between the profit motive in the free marketplace and a health promotion motive. Second, Americans have given special treatments to the health industry in return for medical advances. And third, powerful vested interests (doctors, hospitals, insurance, drug companies) have often used polemics and ideological arguments to defend their favored status, not necessarily actual health outcome data.

So, this leaves the US with the largest, most expensive healthcare system in the world. In 2011 shown here it took in payments of 2.7 trillion dollars, mostly private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid and out-of-pocket. The figure for 2015 was 3.2 trillion dollars, representing 1/6 of the entire economy of the entire Gross Domestic Product. Government’s share of payments was almost 50% in 2016.

This graph shows the dollars spent in 2011 – mostly on hospitals, doctors, drugs, long-term care. Remember that 25% of this pie graph actually goes to administrative costs, not medical services.

In defense of U.S. healthcare, in 2012 then-House-Speaker John Boehner and then Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell famously said, “the U.S. has the finest health care system in the world,” and further that “wealthy foreigners flock to the U.S. because of its cutting edge facilities.”

However, the World Health Organization rates the U.S. 15th in performance (life expectancy and delays in care), and only 37th in overall attainment (including financial and service fairness).

In 2015 the Kaiser Foundation compared the US with 10 other developed countries. Here are their results showing areas in which US is better, equal or lacking.

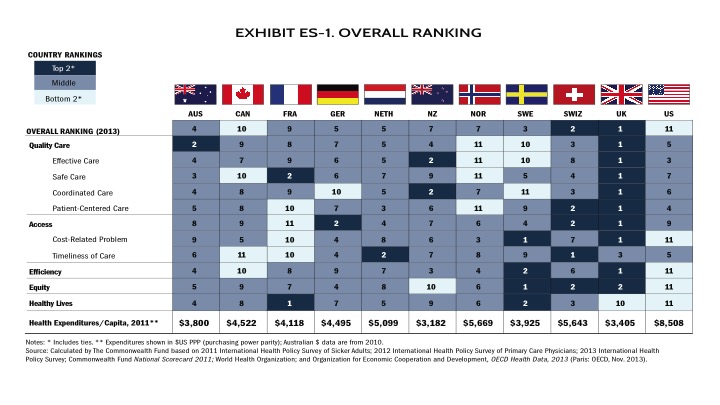

Here are the Commonwealth Fund’s 20-11 rankings – US is in the middle of the pack for most areas but dead last on several others and overall rank.

Source: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/jun/mirror-mirror

Source: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/jun/mirror-mirror

What about “foreigners flocking-for-care”? This pertains to highly specialized treatments available only in certain centers such as Mayo, Cleveland Clinic or Hopkins. Some centers in Florida and Texas do market to wealthy foreigners, who pay the full charge in cash, not discounted insurance rates like the rest or us. Boehner and McConnell pointed to Canadians coming to Michigan hospitals, but the Commonwealth study found that Canada is worst in timeliness and 10th worst overall, just ahead of the US in 11th place, so not surprising.

The further truth is that, according to Centers for Disease Control, 3/4 million Americans go abroad each year for medical treatments, such as for holistic care or dental care, but mostly seeking lower cost.

In the next Segment we will talk about cost, namely how the rising cost of healthcare is affecting our economy, our politics, our society – and some say our very existence.

I’ll see you then.

In Segment 2, I will answer the question, How Did We Get Here? I’ll give a whirlwind tour of the history of medical care in the U.S., and I’ll also look at the birth of health insurance.

Let’s start with looking at healthcare in the Colonial period. The most famous doctor at the time was Benjamin Rush. He – like most reputable professionals of the day – got his medical training in Europe, in his case Edinburgh, Scotland, the leading medical center of the time. Rush was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and served in the Revolutionary Army. He became the “father of American psychiatry” because of his interest in mental illness as a disease, not demon possession.

Rush and other orthodox practitioners in the early Republic –trained in the scientific European tradition– faced competition from a panoply of practitioners in an unlicensed, unregulated “free market.” They peddled nostrums like snake oil and procedures such as blood-letting. Doctors of all types trained like apprentices. The sick were cared for in their homes, with the poor going to almshouses and mentally ill to asylums. Port cities did have public pesthouses for quarantines.

By mid-19th century, orthodox doctors began trying to solidify their place in the market. They did this through training at medical schools, beginning with Harvard, Dartmouth, College of Philadelphia (which eventually became the University of Pennsylvania) and King’s College (which eventually became Columbia). But by 1850 there were now 42 medical schools that often were little more than diploma mills. The course consisted of only two semesters of 3 months each. The medical school needed only 4 faculty, 1 classroom, 1 dissection lab and a charter to grant degrees. These schools were highly profitable.

In 1847, the AMA (American Medical Association) was founded by the orthodox physicians.

Meanwhile, the era of scientific medicine was blossoming in Austria, Britain, Germany and France. Here are some milestones – anesthesia, microbiology study of invisible germs, antiseptic surgery technique and x-rays.

In America, by the turn of the century, doctors and the AMA sought to further shore up their legitimacy by reforming medical education. States began requiring more formal education as a condition for licensure. The Association of Medical Colleges was founded in 1876. In 1893, Dr. William Welch brought to Johns Hopkins University the German model of education based on 3 or 4 years of training in clinical sciences. Industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie hired Abraham Flexner in 1910 to draw up a blueprint for medical school reform. Flexner is widely credited with ushering in the era of modern medicine in this country.

In the early 20th century, doctors enjoyed prestige and independence. Courts rules against corporations practicing medicine, ensuring the pre-eminence of private practice. Doctors joined together in hospitals to take care of growing populations in big cities, and to exploit emerging surgical and diagnostic technologies.

This brings us to health insurance. Surgery (which made great advances during the Civil War and World War I) and hospitals were becoming expensive. So in 1929, Baylor College started the first pre-paid hospital insurance. Baylor’s 1,200 teachers each paid 50 cents per month to cover up to 21 days of hospitalization. Surgeons and hospitals quickly embraced this arrangement, and the Baylor plan became the Blue Cross plan in Minnesota in 1933 and Texas in 1934. By 1950, just 15 years later, Blue Cross covered 57% of the population.

Here’s how it happened. After World War I, the war-torn countries of Europe, like Germany, were in turmoil. Social insurance, including healthcare, helped reestablish some social stability there. But in this country, politicians opposed Teddy Roosevelt’s plan to set up national health insurance for factory workers, calling public insurance a “Prussian menace”. Labor unions saw public health insurance as an encroachment on their special role to ensure worker benefits. The AMA also opposed public health insurance as a potential “interference with the practice of medicine.”

Then during World War II, wages were frozen, but companies were allowed to give health insurance benefits instead. This sewed the seeds of the employer-based health insurance system. In 1948 the Supreme Court decided that unions could use health benefits in collective bargaining agreements. Then in 1954 Congress made employer-paid health premiums non-taxable. By the mid-1960s employer-paid health insurance was nearly universal.

Let’s summarize the history of medicine from Rush to Medicare. In the Colonial period and early Republic there was intense competition among doctors of all stripes, those that tried to understand the scientific basis of disease and those who peddled remedies on a trial-and-error basis (referred to as “empirical”), relying mostly on their placebo effect. We still see vestiges of this early competition today in the rivalry between MDs, DOs, chiropractors and podiatrists. During the industrial period, little by little science-based orthodox physicians in the European tradition prevailed over their rivals introducing advances in surgery, diagnosis and infection control. They shored up their gains with institutions such as the AMA, hospitals, and eventually insurance.

In the next Segment, we will look at reform movements, starting with Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s. We will also look at why later reforms failed and where that leaves us now.

I’ll see you then.

This is the first of a 10-part series in which Duncan MacLean MD explains the U.S. healthcare problem and how to fix it. Dr. MacLean has 40 years experience with medical practice and healthcare policy.

You know, almost every day my patients have been asking me, What is the problem with U.S. healthcare? Of course, I couldn’t really answer in the middle of busy office hours.

“Now I have to tell you It’s an unbelievably complex subject. Nobody knew healthcare could be so complicated.”

“So complicated,” indeed. . .

Healthcare is more complicated than just “repeal & replace Obama-care”. Voters who supported Donald Trump in the 2016 election said that they knew that all along. They just wanted someone to fix the system. They didn’t care about the complicated details.

But just how complicated is healthcare? Does it really need to be that complicated? And can it be fixed?

Please join me over the next 10 segments to talk about this. I’ve been in healthcare for 40 years, as a doctor, teacher and administrator. I’ve worked in private practice, a non-profit teaching hospital, for-profit business, and government healthcare. I’ve served on state and federal commissions.

More importantly I’ve been a small businessman and have raised a family. So I know the system from both the outside as a father and employee, and from the inside, including some dark secret corners.

Come along as I explain all these things. You might be surprised at some of my answers.

Here are some of the questions I’ll tackle in future segments:

– How did we get here?

– What is the problem

– Why is the healthcare problem important?

– Can healthcare be fixed?

Spoiler alert on that last one – I hope so. And in the last segment I will tell you about a fix that actually worked — 25 years ahead of its time.

I hope you’ll queue up the next segment. I’ll see you then.

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/rankings-and-ratings/ibm-watson-names-100-top-hospitals.html

2019 Study Finds Top-Performing U.S. Hospitals Provide Better Care at Lower Cost and Higher Profit Margins than Peers Evaluated in the Study

ARMONK, N.Y., March 4, 2019 /PRNewswire/ — IBM Watson Health™ (NYSE: IBM) today published its 100 Top Hospitals® annual study identifying top–performing hospitals in the U.S. This study spotlights the best–performing hospitals in the U.S. based on a balanced scorecard using publicly available data for clinical, operational, and patient satisfaction metrics. The study is part of IBM Watson Health’s commitment to leveraging science and data to advance health and it has been conducted annually since 1993.

Overall, the Watson Health 100 Top Hospitals® study found that the top-performing hospitals in the country achieved better risk-adjusted outcomes while maintaining both a lower average cost per patient and higher profit margin than peer group hospitals that were part of the study.

“At a time when research shows that the U.S. spends nearly twice as much on healthcare as other high-income countries, yet has less effective population health outcomes1, the 100 Top Hospitals are setting a different example by delivering consistently better care at a lower cost,” said Ekta Punwani, 100 Top Hospitals® program leader at IBM Watson Health.

Kyu Rhee, M.D., M.P.P., vice president and chief health officer at IBM Watson Health, added: “From small community hospitals to major teaching hospitals, these diverse hospitals have demonstrated that quality care, higher patient satisfaction, and operational efficiency can be achieved together. In this era of big data, analytics, transparency, and patient empowerment, it is essential that we learn from these leading hospitals and work to spread their best practices to our entire health system which could translate into over 100K more lives saved, nearly 40K less complications, over 150K fewer readmissions, and over $8 billion in savings.”

Following were the key performance measurements on which 100 Top Hospitals showed the most significant average outperformance versus non-winning peer group hospitals (full study results available here):

The IBM Watson Health 100 Top Hospitals winners outperformed peer group hospitals within all 10 clinical and operational performance benchmarks evaluated in the study: risk-adjusted inpatient mortality index, risk-adjusted complications index, mean healthcare-associated infection index, mean 30-day risk-adjusted mortality rate, mean 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rate, severity-adjusted length of stay, mean emergency department throughput, case mix- and wage-adjusted inpatient expense per discharge, adjusted operating profit margin, and HCAHPS score.

Extrapolating the results of this year’s study, if all Medicare inpatients received the same level of care as those treated in the award-winning facilities:

In addition to the 100 Top Hospitals, the IBM Watson Health study also recognizes the 100 Top Hospitals Everest Award winners. These are hospitals that earned the 100 Top Hospitals designation and also are among the 100 top for rate of improvement during a five-year period. This year, there are 15 Everest Award winners.

To conduct the 100 Top Hospitals study, IBM Watson Health researchers evaluated 3,156 short-term, acute care, non-federal U.S. hospitals. All research was based on the following public data sets: Medicare cost reports, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) data, and core measures and patient satisfaction data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Compare website. Hospitals do not apply for awards, and winners do not pay to market this honor.

For more information, visit www.100tophospitals.com.

Here are the winning hospitals, by category, with asterisks indicating the Everest Award winners:

Major Teaching Hospitals

Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center – Chicago, IL

Ascension Providence Hospital – Southfield, MI

Banner – University Medical Center Phoenix – Phoenix, AZ

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center – Los Angeles, CA

Garden City Hospital – Garden City, MI*

Mayo Clinic Hospital – Jacksonville, FL

Mount Sinai Medical Center – Miami Beach, FL

NorthShore University HealthSystem – Evanston, IL

Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center – Hartford, CT

Spectrum Health Hospitals – Grand Rapids, MI

St. Joseph Mercy Hospital – Ann Arbor, MI*

St. Luke’s University Hospital – Bethlehem – Bethlehem, PA

The Miriam Hospital – Providence, RI

UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital – Aurora, CO*

University of Utah Hospital – Salt Lake City, UT

Teaching Hospitals

Abbott Northwestern Hospital – Minneapolis, MN

Aspirus Wausau Hospital – Wausau, WI

Brandon Regional Hospital – Brandon, FL

BSA Health System – Amarillo, TX

CHRISTUS St. Michael Health System – Texarkana, TX*

Good Samaritan Hospital – Cincinnati, OH

Lakeland Medical Center – St. Joseph, MI

Mercy Hospital St. Louis – St. Louis, MO

Monmouth Medical Center – Long Branch, NJ

Morton Plant Hospital – Clearwater, FL

Mount Carmel St. Ann’s – Westerville, OH

Park Nicollet Methodist Hospital – St. Louis Park, MN

Parkview Regional Medical Center – Fort Wayne, IN*

PIH Health Hospital – Whittier – Whittier, CA

Riverside Medical Center – Kankakee, IL

Rose Medical Center – Denver, CO*

Sentara Leigh Hospital – Norfolk, VA*

Sky Ridge Medical Center – Lone Tree, CO

SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital – Madison – Madison, WI

St. Luke’s Hospital – Cedar Rapids, IA

St. Mark’s Hospital – Salt Lake City, UT*

Sycamore Medical Center – Miamisburg, OH

UCHealth Poudre Valley Hospital – Fort Collins, CO

Utah Valley Hospital – Provo, UT*

West Penn Hospital – Pittsburgh, PA

Large Community Hospitals

Advocate Sherman Hospital – Elgin, IL*

Banner Del E. Webb Medical Center – Sun City West, AZ

Baylor Scott & White Medical Center – Grapevine – Grapevine, TX

Hoag Hospital Newport Beach – Newport Beach, CA

IU Health Bloomington Hospital – Bloomington, IN*

Mease Countryside Hospital – Safety Harbor, FL

Memorial Hermann Memorial City Medical Center – Houston, TX

Mercy Health – Anderson Hospital – Cincinnati, OH

Mercy Health – St. Rita’s Medical Center – Lima, OH

Mercy Hospital – Coon Rapids, MN

Mercy Hospital Oklahoma City – Oklahoma City, OK

Northwestern Medicine Central DuPage Hospital – Winfield, IL

Sarasota Memorial Hospital – Sarasota, FL

Scripps Memorial Hospital La Jolla – La Jolla, CA

St. Clair Hospital – Pittsburgh, PA

St. David’s Medical Center – Austin, TX

St. Joseph’s Hospital – Tampa, FL*

Texas Health Harris Methodist Hospital Southwest Fort Worth – Fort Worth, TX

University of Maryland St. Joseph Medical Center – Towson, MD

WellStar West Georgia Medical Center – LaGrange, GA

Medium Community Hospitals

AdventHealth Wesley Chapel – Wesley Chapel, FL

Dupont Hospital – Fort Wayne, IN

East Cooper Medical Center – Mt. Pleasant, SC

East Liverpool City Hospital – East Liverpool, OH*

Garden Grove Hospital Medical Center – Garden Grove, CA

IU Health North Hospital – Carmel, IN

IU Health West Hospital – Avon, IN

Logan Regional Hospital – Logan, UT

Memorial Hermann Katy Hospital – Katy, TX

Mercy Health – Clermont Hospital – Batavia, OH

Mercy Hospital Northwest Arkansas – Rogers, AR

Mercy Medical Center – Cedar Rapids, IA

Montclair Hospital Medical Center – Montclair, CA

Mountain View Hospital – Payson, UT

Northwest Medicine Delnor Hospital – Geneva, IL

St. Luke’s Anderson Campus – Easton, PA

St. Vincent’s Medical Center Clay County – Middleburg, FL

UCHealth Medical Center of the Rockies – Loveland, CO

West Valley Medical Center – Caldwell, ID

Wooster Community Hospital – Wooster, OH

Small Community Hospitals

Alta View Hospital – Sandy, UT

Aurora Medical Center – Two Rivers, WI

Brigham City Community Hospital – Brigham City, UT

Buffalo Hospital – Buffalo, MN

Cedar City Hospital – Cedar City, UT

Hill Country Memorial Hospital – Fredericksburg, TX

Lakeview Hospital – Bountiful, UT

Lone Peak Hospital – Draper, UT

Marshfield Medical Center – Rice Lake, WI

Nanticoke Memorial Hospital – Seaford, DE

Parkview Noble Hospital – Kendallville, IN

Parkview Whitley Hospital – Columbia City, IN*

Piedmont Mountainside Hospital – Jasper, GA

San Dimas Community Hospital – San Dimas, CA

Seton Medical Center Harker Heights – Harker Heights, TX

Southern Tennessee Regional Health System – Lawrenceburg, TN

Spectrum Health Zeeland Community Hospital – Zeeland, MI

St. John Owasso Hospital – Owasso, OK

St. Luke’s Hospital – Quakertown – Quakertown, PA

Stillwater Medical Center – Stillwater, OK*