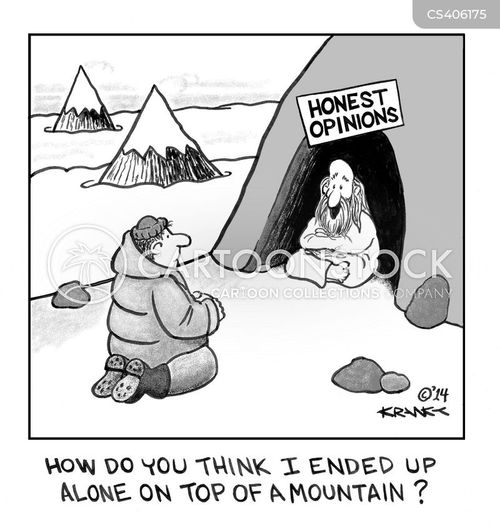

Cartoon – Honest Opinions

Oakland, Calif.-based Kaiser Permanente reported higher revenue for its nonprofit hospital and health plan units in the first nine months of this year, but the system ended the period with lower net income.

Here are four things to know:

1. Kaiser’s operating revenue climbed to $59.7 billion in the first nine months of 2018, according to recently released bondholder documents. That’s up 9.6 percent from revenue of $54.5 billion in the same period of 2017.

2. Kaiser’s health plan membership increased from 11.8 million members in December 2017 to 12.2 million members as of Sept. 30, 2018.

3. During the first nine months of this year, Kaiser’s operating expenses totaled $57.7 billion. That’s up from $52.2 billion in the first nine months of 2017. In the third quarter of 2018 alone, Kaiser’s expenditures included capital spending of $760 million, which includes investments in upgrading and opening new facilities, as well as in technology.

4. Kaiser ended the first nine months of 2018 with net income of $2.9 billion, down 23 percent from net income of $3.8 billion in the same period of 2017.

Most hospital and health system leaders are interested in value-based contracting when it comes to their supply chains, but a new Premier survey shows a lack of opportunities to lock down contracts with suppliers.

Among 200 C-suite executives and supply chain leaders, 73 percent said their health systems prioritize value-based contracting when looking to improve their return on investment.

IMPACT

In perhaps another sign of the inevitability of value-based care, 81 percent of respondents said they would be interested in more suppliers offering value-based contracting options.

Despite that, only 38 percent said they had participated in value-added or risk-based contracting with suppliers or pharmaceutical companies.

There are some barriers. When asked if they had considered participating in value-based contracts with suppliers with both up- and downside risk/reward, 55 percent said they didn’t know enough about shared risk contracts. Another 20 percent said they’re actively considering such contracts; 16 percent are already participating in them.

As for why many providers haven’t yet taken part in value-based or risk-based contracting with suppliers, 67 percent said it’s due to not having been engaged by a supplier. About 11 percent said it doesn’t align with the organization’s strategy.

WHAT ELSE YOU SHOULD KNOW

Respondents provided some examples of value-based contracts they had implemented, and at the top of the list was surgical services at 13 percent.

Following that was purchased services (11 percent); cardiovascular (11 percent); pharmacy and materials management (9 percent); nursing (8 percent), imaging and lab (6 percent); and facilities (5 percent).

Data was the most common challenge, cited by 22 percent of respondents. That was followed by internal communications (14 percent); coordination with suppliers (12 percent); infrastructure support (11 percent); and physician buy-in (10 percent).

THE TREND

Research this year from Sage Growth Partners highlighted the challenges providers face in succeeding under value-based contracting. Slightly more than two-thirds of the survey’s 100 respondents said value-based care has provided them with a return on investment, but many have had to supplement their electronic health records with third-party population health management solutions to get the most bang for their buck.

The use of artificial intelligence in healthcare is still nascent in some respects. Machine learning shows potential to leverage AI algorithms in a way that can improve clinical quality and even financial performance, but the data picture in healthcare is pretty complex. Crafting an effective AI dashboard can be daunting for the uninitiated.

A balance needs to be struck: Harnessing myriad and complex data sets while keeping your goals, inputs and outputs as simple and focused as possible. It’s about more than just having the right software in place. It’s about knowing what to do with it, and knowing what to feed into it in order to achieve the desired result.

In other words, you can have the best, most detailed map in the world, but it doesn’t matter if you don’t have a compass.

AI DASHBOARD MUST HAVES

Jvion Chief Product Officer John Showalter, MD, said the most important thing an AI dashboard can do is drive action. That means simplifying the outputs, so perhaps two of the components involved are AI components, and the rest is information an organization would need to make a decision.

He’s also a proponent of color coding or iconography to simplify large amounts of information — basic measures that allow people to understand the information very quickly.

“And then to get to actionability, you need to integrate data into the workflow, and you should probably have single sign-on activity to reduce the login burden, so you can quickly look up the information when you need it without going through 40 steps.”

According to Eldon Richards, chief technology officer at Recondo Technology, there have been a number of breakthroughs in AI over the years, such that machine learning and deep learning are often matching, and sometimes exceeding, human capability for certain tasks.

What that means is that dashboards and related software are able to automate things that, as of a few years ago, weren’t feasible with a machine — things like radiology, or diagnosing certain types of cancer.

“When dealing with AI today, that mostly means machine learning. The data vendor trains the model on your needs to match the data you’re going to feed into the system in order to get a correct answer,” Richards said. “An example would be if the vendor trained the model on hospitals that are not like my hospital, and payers unlike who I deal with. They could produce very inaccurate numbers. It won’t work for me.”

A health system would also want to pay close attention to the ways in which AI can fail. The technology can still be a bit fuzzy at times.

“Sometimes it’s not going to be 100 percent accurate,” said Richards. “Humans wouldn’t be either, but it’s the way they fail. AI can fail in ways that are more problematic — for example, if I’m trying to predict cancer, and the algorithm says the patient is clean when they’re not, or it might be cancer when it’s not. In terms of the dashboard, you want to categorize those types of values on data up front, and track those very closely.”

KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS FOR AI AND ML

Generally speaking, you want a key performance indicator based around effectiveness. You want a KPI around usage. And you want some kind of KPI that tracks efficiency — Is this saving us time? Are we getting the most bang for the buck?

The revenue cycle offers a relevant example, where the dashboard can be trained to look at something like denials. KPIs that track the efficiency of denials, and the total denials resolved with a positive outcome, can help health systems determine what percentage of the denials were fixed, and how many they got paid for. This essentially tracks the time, effort, and ultimately the efficacy of the AI.

“You start with your biggest needs,” said Showalter. “You talk about sharing outcomes — what are we all working toward, what can we all agree on?”

“Take falls as an example,” Showalter added. “The physician maybe will care about the biggest number of falls, and the revenue cycle guy will care about that and the cost associated with those falls. And maybe the doctors and nurses are less concerned about the costs, but everybody’s concerned about the falls, so that becomes your starting point. Everyone’s focused on the main outcome, and then the sub-outcomes depend on the role.”

It’s that focus on specific outcomes that can truly drive the efficacy of AI and machine learning. Dr. Clemens Suter-Crazzolara, vice president of product management for health and precision medicine at SAP, said it’s helpful to parse data into what he called limited-scope “chunks” — distinct processes a provider would like to tackle with the help of artificial intelligence.

Say a hospital’s focus is preventing antibiotic resistance. “What you then start doing,” said Suter-Crazzolara, “is you say, ‘I have these patients in the hospital. Let’s say there’s a small-scale epidemic. Can I start collecting that data and put that in an AI methodology to make a prediction for the future?’ And then you determine, ‘What is my KPI to measure this?’

“By working on a very distinct scenario, you then have to put in the KPIs,” he said.

PeriGen CEO Matthew Sappern said a good litmus test for whether a health system is integrating AI an an effective way is whether it can be proven that its outcomes are as good as those of an expert. Studies that show the system can generate the same answers as a panel of experts can go a long way toward helping adoption.

The reason that’s so important, he said, is that the accuracy of the tools can be all over the place. The engine is only as good as the data you put into it, and the more data, the better. That’s where electronic health records have been a boon; they’ve generated a huge amount of data.

Even then, though, there can be inconsistencies, and so some kind of human touch is always needed.

“At any given time, something is going on,” said Sappern. “To assume people are going to document in 30-second increments is kind of crazy. So a lot of times nurses and doctors go back and try to recreate what’s on the charts as best they can.

“The problem is that when you go back and do chart reviews, you see things that are impossible. As you curate this data, you really need to have an expert. You need one or two very well-seasoned physicians or radiologists to look for these things that are obviously not possible. You’d be surprised at the amount of unlikely information that exists in EMRs these days.”

Having the right team in place is essential, all the more so because of one of the big misunderstandings around AI: That you can simply dump a bunch of data into a dashboard, press a button, and come back later to see all of its findings. In reality, data curation is painstaking work.

“Machine learning is really well suited to specific challenges,” said Sappern. “It’s got great pattern recognition, but as you are trying to perform tasks that require a lot of reasoning or a lot of empathy, currently AI is not really great at that.

“Whenever we walk into a clinical setting, a nurse or a number of nurses will raise their hands and say, ‘Are you telling me this machine can predict the risk of stroke better than I can?’ And the immediate answer is absolutely not. Every single second the patient is in bed, we will persistently look out for those patterns.”

Another area in which a human touch is needed is in the area of radiological image interpretation. The holy grail, said Suter-Crazzolara, would be to have a supercomputer into which one could feed an x-ray from a cancer patient, and which would then identify the type of cancer present and what the next steps should be.

“The trouble is,” said Suter-Crazzolara, “there’s often a lack of annotated data. You need training sets with thousands of prostate cancer types on these images. The doctor has to sit down with the images and identify exactly what the tumors look like in those pictures. That is very, very hard to achieve.

“Once you have that well-defined, then you can use machine learning and create an algorithm that can do the work. You have to be very, very secure in the experimental setup.”

HOW TO TELL IF THE DASHBOARD IS WORKING

It’s possible for machine learning to continue to learn the more an organization uses the system, said Richards. Typically, the AI dashboard would provide an answer back to the user, and the user would note anything that’s not quite accurate and correct it, which provides feedback for the software to improve going forward. Richards recommends a dashboard that shows failure rate trends; if it’s doing its job, the failure rate should improve over time.

“AI is a means to an end,” he said. “Stepping back a little bit, if I’m designing a dashboard I might also map out what functions I would apply AI to, and what the coverage looks like. Maybe a heat map showing how I’m doing in cost per transaction.”

Suter-Crazzolara sees these dashboards as the key to creating an intelligent enterprise because it allows providers to innovate and look at data in new ways, which can aid everything from the diagnosis of dementia to detecting fraud and cutting down on supply chain waste.

“AI is at a stage that is very opportune,” he said, “because artificial intelligence and machine learning have been around for a long time, but at the moment we are in this era of big data, so every patient is associated with a huge amount of data. We can unlock this big data much better than in the past because we can create a digital platform that makes it possible to connect and unlock the data, and collaborate on the data. At the moment, you can build very exciting algorithms on top of the data to make sense of that information.”

MARKETPLACE

If a health system decides to tap a vendor to handle its AI and machine learning needs, there are certain things to keep in mind. Typically, vendors will already have models created from certain data sets, which allows the software to perform a function that was learned from that data. If a vendor trained a model with a hospital whose characteristic differ from your own, there can be big differences in the efficacy of those models.

Richards suggested reviewing what data the vendor used to train its model, and to discuss with them how much data they need in order to construct a model with the utmost accuracy. He suggests talking to vendor to understand how well they know your particular space.

“In most cases I think they’ve got a good handle on the technology itself, but they need to know the space and the nuances of it,” said Richards. He would interview them to make sure he was comfortable with their depth of knowledge.

That will ensure the technology works as effectively as possible — an important consideration, since AI likely isn’t going away anytime soon.

“We’re seeing not just the hype, but we’re definitely seeing some valuable results coming,” said Richards. “We’re still somewhat at the beginning of that. Breakthroughs in the space are happening every day.”

The Trump administration has labored zealously to cut federal regulations, but its latest move has still astonished some experts on health care: It has asked for recommendations to relax rules that prohibit kickbacks and other payments intended to influence care for people on Medicare or Medicaid.

The goal is to open pathways for doctors and hospitals to work together to improve care and save money. The challenge will be to accomplish that without also increasing the risk of fraud.

With its request for advice, the administration has touched off a lobbying frenzy. Health care providers of all types are urging officials to waive or roll back the requirements of federal fraud and abuse laws so they can join forces and coordinate care, sharing cost reductions and profits in ways that would not otherwise be allowed.

From hundreds of letters sent to the government by health care executives and lobbyists in the last few weeks, some themes emerge: Federal laws prevent insurers from rewarding Medicare patients who lose weight or take medicines as prescribed. And they create legal risks for any arrangement in which a hospital pays a bonus to doctors for cutting costs or achieving clinical goals.

The existing rules are aimed at preventing improper influence over choices of doctors, hospitals and prescription drugs for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. The two programs cover more than 100 million Americans and account for more than one-third of all health spending, so even small changes in law enforcement priorities can have big implications.

Federal health officials are reviewing the proposals for what they call a “regulatory sprint to coordinated care” even as the Justice Department and other law enforcement agencies crack down on health care fraud, continually exposing schemes to bilk government health programs.

“The administration is inviting companies in the health care industry to write a ‘get out of jail free card’ for themselves, which they can use if they are investigated or prosecuted,” said James J. Pepper, a lawyer outside Philadelphia who has represented many whistle-blowers in the industry.

Federal laws make it a crime to offer or pay any “remuneration” in return for the referral of Medicare or Medicaid patients, and they limit doctors’ ability to refer patients to medical businesses in which the doctors have a financial interest, a practice known as self-referral.

These laws “impose undue burdens on physicians and serve as obstacles to coordinated care,” said Dr. James L. Madara, the chief executive of the American Medical Association. The laws, he said, were enacted decades ago “in a fee-for-service world that paid for services on a piecemeal basis.”

Melinda R. Hatton, senior vice president and general counsel of the American Hospital Association, said the laws stifle “many innocuous or beneficial arrangements” that could provide patients with better care at lower cost.

Hospitals often say they want to reward doctors who meet certain goals for improving the health of patients, reducing the length of hospital stays and preventing readmissions. But federal courts have held that the anti-kickback statute can be violated if even one purpose of the remuneration is to induce referrals or generate business for the hospital.

The premise of the kickback and self-referral laws is that health care providers should make medical decisions based on the needs of patients, not on the financial interests of doctors or other providers.

Health care providers can be fined if they offer financial incentives to Medicare or Medicaid patients to use their services or products. Drug companies have been found to violate the law when they give kickbacks to pharmacies in return for recommending their drugs to patients. Hospitals can also be fined if they make payments to a doctor “as an inducement to reduce or limit services” provided to a Medicare or Medicaid beneficiary.

Doctors, hospitals and drug companies are urging the Trump administration to provide broad legal protection — a “safe harbor” — for arrangements that promote coordinated, “value-based care.” In soliciting advice, the Trump administration said it wanted to hear about the possible need for “a new exception to the physician self-referral law” and “exceptions to the definition of remuneration.”

Almost every week the Justice Department files another case against health care providers. Many of the cases were brought to the government’s attention by people who say they saw the bad behavior while working in the industry.

“Good providers can work within the existing rules,” said Joel M. Androphy, a Houston lawyer who has handled many health care fraud cases. “The only people I ever hear complaining are people who got caught cheating or are trying to take advantage of the system. It would be disgraceful to change the rules to appease the violators.”

But the laws are complex, and the stakes are high. A health care provider who violates the anti-kickback or self-referral law may face business-crippling fines under the False Claims Act and can be excluded from Medicare and Medicaid, a penalty tantamount to a professional death sentence for some providers.

Federal law generally prevents insurers and health care providers from offering free or discounted goods and services to Medicare and Medicaid patients if the gifts are likely to influence a patient’s choice of a particular provider. Hospital executives say the law creates potential problems when they want to offer social services, free meals, transportation vouchers or housing assistance to patients in the community.

Likewise, drug companies say they want to provide financial assistance to Medicare patients who cannot afford their share of the bill for expensive medicines.

AstraZeneca, the drug company, said that older Americans with drug coverage under Part D of Medicare “often face prohibitively high cost-sharing amounts for their medicines,” but that drug manufacturers cannot help them pay these costs. For this reason, it said, the government should provide legal protection for arrangements that link the cost of a drug to its value for patients.

Even as health care providers complain about the broad reach of the anti-kickback statute, the Justice Department is aggressively pursuing violations.

A Texas hospital administrator was convicted in October for his role in submitting false claims to Medicare for the treatment of people with severe mental illness. Evidence at the trial showed that he and others had paid kickbacks to “patient recruiters” who sent Medicare patients to the hospital.

The owner of a Florida pharmacy pleaded guilty last month for his role in a scheme to pay kickbacks to Medicare beneficiaries in exchange for their promise to fill prescriptions at his pharmacy.

The Justice Department in April accused Insys Therapeutics of paying kickbacks to induce doctors to prescribe its powerful opioid painkiller for their patients. The company said in August that it had reached an agreement in principle to settle the case by paying the government $150 million.

The line between patient assistance and marketing tactics is sometimes vague.

This month, the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services refused to approve a proposal by a drug company to give hospitals free vials of an expensive drug to treat a disorder that causes seizures in young children. The inspector general said this arrangement could encourage doctors to continue prescribing the drug for patients outside the hospital, driving up costs for consumers, Medicare, Medicaid and commercial insurance.