Abstract

- Issue: The Affordable Care Act (ACA) transformed the market for individual health insurance, so it is not surprising that insurers’ transition was not entirely smooth. Insurers, with no previous experience under these market conditions, were uncertain how to price their products. As a result, they incurred significant losses. Based on this experience, some insurers have decided to leave the ACA’s subsidized market, although others appear to be thriving.

- Goals: Examine the financial performance of health insurers selling through the ACA’s marketplace exchanges in 2015 — the market’s most difficult year to date.

- Method: Analysis of financial data for 2015 reported by insurers from 48 states and D.C. to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

- Findings and Conclusions: Although health insurers were profitable across all lines of business, they suffered a 10 percent loss in 2015 on their health plans sold through the ACA’s exchanges. The top quarter of the ACA exchange market was comfortably profitable, while the bottom quarter did much worse than the ACA market average. This indicates that some insurers were able to adapt to the ACA’s new market rules much better than others, suggesting the ACA’s new market structure is sustainable, if supported properly by administrative policy.

Background

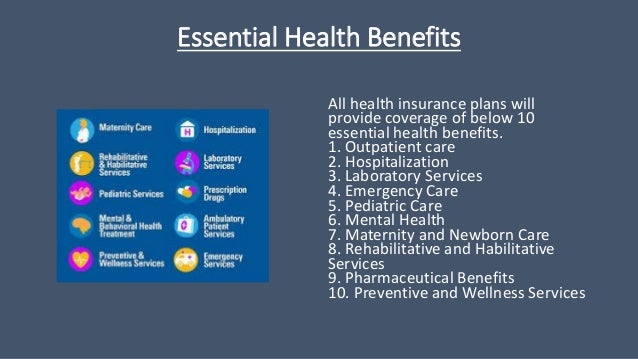

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) created an entirely new marketplace for individual health insurance through three key reforms: a prohibition against charging more for premiums based on subscribers’ health status or risk, providing substantial subsidies for millions of people to purchase individual coverage, and an “exchange” structure that facilitates comparison shopping among insurance plans. In addition, the ACA limits the percentage of premiums insurers can devote to profit and administrative expenses and requires state or federal regulators to evaluate any rate increases requested by insurers.

Because the ACA transformed the market so fundamentally, it is no surprise that the transition was not entirely smooth.1 Because insurers lacked experience with these market conditions, they were uncertain about how to price their products2 and some had significant losses.3 A number of newly established insurers that focused on the individual market went out of business entirely4 and a substantial number of others decided to leave the individual market.5Others, however, appear to be thriving.6

Overall, insurers lost money in the ACA’s individual market in each of the first three years. To date, 2015 has been the worst year, but some insurers did better than others.7 To better understand this varied financial performance, this issue brief analyzes financial data for 2015 reported by insurers from 48 states and D.C. to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).8 It is important to analyze marketwide financial performance because the experience in particular states or among specific insurers may not represent conditions generally. Lessons from better-performing parts of the market in the ACA’s most difficult year could help improve areas with worse performance and encourage the adoption of policies that avoid future market turmoil.

We focus on data for “qualified health plans” (QHPs) — that is, products that insurers are certified to sell through the ACA’s “marketplace” exchange. Although insurers also sell QHPs outside the exchanges, premium subsidies are available only for plans sold on the exchanges. Thus, the exchanges account for over three-fourths of QHP sales.9 For insurers to be willing to participate in the exchanges, they must be able to achieve adequate financial results. In turn, their participation is critical to providing coverage and choice to the millions of Americans who are eligible for subsidized insurance.

Based on our analysis of “credible” insurers (i.e., those with more than 1,000 members), we find that QHPs suffered losses of 10 percent overall in 2015. The top quarter of insurers had profits of 7 percent while the bottom quarter had losses of 37 percent. This indicates that some insurers were able to adjust to the ACA’s new market rules much better than others. Because financial performance has improved substantially since then,10 the ability of some insurers to achieve acceptable results even in the ACA’s worst year confirms analyses by the Congressional Budget Office and the former White House Council of Economic Advisors that the ACA’s market structure is sustainable, if properly supported by administrative policy.11

Study Findings

Variation in Profitability

We identified 214 insurers across different states in 2015 with more than 1,000 members in QHPs. Overall, these insurers’ marketplace plans did not fare well in 2015. As shown in Exhibit 1, across the ACA market as a whole, insurers lost almost 10 percent of premiums from their QHP products, amounting to a loss of $33 per member per month (pmpm). This compares with a 6 percent loss overall in 2014 (or $19 pmpm; data not shown). Losses were large in 2015, even after accounting for substantial reinsurance payments of $45 pmpm (or 13% of premium) that insurers received to help offset higher-cost patients. Without these reinsurance payments, losses would have totaled $78 pmpm.

Although insurers’ losses were substantial, they were not as dismal as some pessimistic analysts had projected.12Moreover, some insurers did substantially better than the market overall. Dividing insurers into quartiles based on profitability,13 the top quarter generated rather handsome profits overall of 7 percent, amounting to $25 pmpm — $58 pmpm better than the market average. These profits resulted from two key factors: somewhat higher QHP premiums of $20 pmpm over the market average, coupled with somewhat lower net medical costs of $39 pmpm less than the market average. Better-performing insurers received the same amount of help from reinsurance and risk adjustment as the average insurers. This illustrates that although their medical claims were somewhat lower than the market average, the better-performing insurers did not have substantially healthier enrollees.14 Instead, they appear to have done a better job of either anticipating QHP subscribers’ true medical costs or of controlling those costs (or both).

In contrast, QHP insurers in the bottom quartile did substantially worse on both premiums charged and medical costs incurred. Their net medical costs were $66 pmpm greater than the market average (or $105 more than the best-performing quartile) and their premiums were $14 pmpm lower than the market average. It appears that the premiums of worse-performing insurers failed to anticipate the extent of medical claims their QHP subscribers would generate. These higher claims were partially offset by reinsurance and risk-adjustment payments totaling $68 pmpm — an amount that is 51 percent higher than the market average — but this was not sufficient to offset premiums that were substantially underpriced. Thus, the bottom quartile had an overall loss of 37 percent of premiums — or $120 pmpm, which was three-and-a-half times more than the average loss.

Change in Profitability

To further understand how insurers’ experiences differed in 2015, we analyzed how QHP financial performance changed from 2014 to 2015 (Exhibit 2). Focusing on the 175 insurers who had at least 1,000 members in each year, we divided insurers according to whether they were profitable or unprofitable in 2015.

Among the more than two-thirds of insurers that were unprofitable in 2015, losses increased substantially from 2014: from 10 percent to 17 percent of premium. More than two-thirds of these insurers were also unprofitable in 2014 and their loss levels were similar each year (20% of premium, data not shown). Thus, the increased losses overall were driven by the 38 insurers that went from an 11 percent profit in 2014 to a 9 percent loss in 2015 (data not shown).

Profitable insurers in 2015 were also profitable in 2014, on the whole, but their operating margins dropped, from 8 percent to 5 percent. Three-quarters of these insurers were also profitable in 2014. The group that became profitable in 2015 did so mainly because — in contrast with other insurers — their medical claims declined slightly (data not shown).

Overall, insurers with financial losses did worse in 2015 because net medical costs increased (by 13%, or $40 pmpm) and because their premium increase was only modest (4%, or $13 pmpm). Insurers that had a loss in 2014 increased their premiums 6 percent while those that went from being profitable in 2014 to having a loss in 2015 kept their premiums the same, despite increasing medical costs (data not shown).

Net medical costs for insurers with losses increased primarily because of a 32 percent reduction (or $23 pmpm) in offsetting reinsurance and risk-adjustment payments, and, to some degree, because of a 5 percent increase ($17 pmpm) in gross medical costs. The same pattern was also true for profitable insurers in 2015: their 10 percent increase ($27 pmpm) in net medical costs was due more to the 23 percent decrease ($15 pmpm) in offsetting reinsurance and risk-adjustment payments than to the 4 percent ($12 pmpm) increase in gross medical costs.

In sum, it does not appear that losing insurers suffered substantially from a simple increase in medical claims. Instead, their modest premium increases failed to correct for the previous year’s losses or to anticipate reductions in cost-reducing reinsurance and risk-adjustment payments. Competitive pressures on the exchanges may have caused these insurers to keep their premium increases in check. As for anticipating net medical costs, when insurers set their premiums for 2015, actuaries had only a few months of experience from 2014 on which to base their projections and they did not have the results from the ACA’s reinsurance and risk-adjustment programs. Thus, actuaries lacked the information they needed to make more precise estimates.

It also appears that unprofitable insurers simply were not able to offer prices that could compete well with profitable insurers. On average, the premiums for unprofitable insurers were $20 pmpm less than profitable ones — both in 2014 and 2015 — despite having net medical expenses that were from $41 to $55 greater on a pmpm basis. From these data, we cannot determine to what extent these greater medical expenses are the result of differences in subscribers’ underlying health risks or to differences in insurers’ ability to manage and control health care spending.

Discussion

The fundamental reforms of the Affordable Care Act — subsidizing coverage, establishing insurance exchanges, and making insurance available to people with preexisting conditions — changed market conditions in ways that insurers initially had difficulty predicting.15 Our analysis shows that these difficulties worsened in the second year of full ACA market reforms: insurers suffered a 10 percent loss overall in 2015 compared to a 6 percent loss in 2014 for their qualified health plans.

Our findings, along with other analyses,16 show that this decline was not because of substantially greater medical costs per person. Instead, because insurers had not yet had enough experience under the new market conditions when they filed their rates for 2015, many underpriced their products relative to their members’ health risks. It appears now that this underpricing was a short-term issue. As insurers gained more experience in the reformed market, their financial performance in the ACA’s individual market improved substantially in 2016 and many or most appear to be on their way to profitability in 2017.17

Moreover, insurers in the top quarter of the market in 2015 fared much better than the market average and those in the bottom quarter did much worse. This is a sign of inevitable market “shake out,” as some insurers learn that they are not as well positioned to compete in the new market as are others.18 As worse-performing insurers either leave the market or change their strategies, overall financial performance is improving substantially. Even if some insurers continue to struggle financially, the ability of many to achieve acceptable results in the ACA’s worst year to date suggests — along with other recent evidence19 — that the ACA’s market structure is inherently sustainable in the long run.

Long-run sustainability depends, however, on insurers being able to maintain profitability. As the new administration shifts its regulatory policies and Congress contemplates ACA replacements, new threats to market stability have emerged.20 It was difficult for insurers to achieve profitability when they were unable to predict and accurately price for the impact of changing market rules and implementation policies. As insurers regain their footing after a rocky transition, it would be unfortunate to reintroduce or aggravate elements of uncertainty and instability that they have only recently overcome.