https://time.com/7312361/obamacare-marketplace-health-insurance-cost-increase/

For four years, people buying health care on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace have benefited from government subsidies that made their plans more inexpensive, and thus more accessible.

Now, those subsidies have become a key point of contention between Democrats and Republicans in a government shutdown that went into effect on Oct. 1 after both sides failed to reach a deal.

Democrats want Congress to extend the enhanced premium tax credits first added in 2021; without an extension, the tax credits expire at the end of 2025 and experts say premium prices could double in 2026.

“They know they’re screwed if this debate turns into one about healthcare. And guess what? That’s just what we’re doing. We are making this debate a debate on healthcare,” said U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer, a Democrat from New York, hours before the government shut down.

Republicans say that Democrats want to extend free health care for unauthorized immigrants, a talking point that is not true but that has nevertheless been repeated many times by GOP politicians. (Democrats want to reverse health policy changes that the GOP’s tax law enacted, including limits to federal funding for health care for “lawfully present” immigrants.)

Neither side appears ready to budge, which means that as of right now, people who buy health care on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace are about to be in for some sticker shock. Monthly out-of-pocket costs are set to jump as much as 75% for 2026 because of the disappearance of federal subsidies and higher rates from insurers.

“Most enrollees are going to be facing a double whammy of both higher insurance bills and losing the subsidies that lower much of the cost,” says Matt McGough, a policy analyst at KFF for the Program on the ACA and the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker.

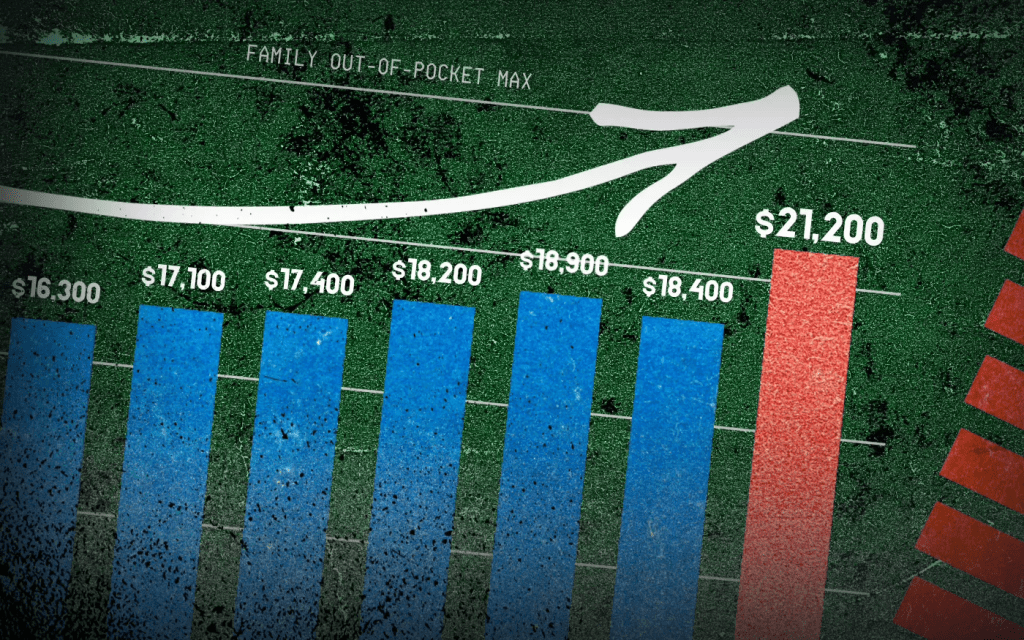

KFF recently calculated that the median rate increase proposed by insurers is 18%, more than double last year’s 7% median proposed increase. But the actual blow to patients is going to be much higher. That’s because enhancements to premium tax credits are set to expire at the end of 2025.

Around 93% of marketplace enrollees—19.3 million people—received the enhanced premium tax credits, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, saving them $700 yearly on average. For some people, the tax credits meant that they wouldn’t have to pay an insurance premium if they chose certain plans. For others, it meant getting hundreds of dollars off a health plan they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to afford.

Premium tax credits helped people afford plans on the Affordable Care Act marketplaces between 2014 and 2021. Then, in 2021, enhancements to those premium tax credits went into effect with the American Rescue Plan. Before 2021, premium tax credits were only available to people making between 100-400% of the federal poverty limit—so between $25,8200 and $103,280 for a family of three in 2025. The enhanced tax credits were expanded to households with incomes over 400% of the federal poverty limit, and were also made more generous for everyone. That wide range meant they subsidized coverage for people who otherwise would not have gotten any break on their premiums.

The enhancements to the premium tax credits, which are set to expire at the end of 2025, significantly boosted enrollment in Affordable Care Act marketplace plans. More than 20 million people enrolled in marketplace coverage in 2024, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, up from 11.2 million in February 2021, before the enhancements to the tax credits.

With costs being lowered by half, individuals and families decided, ‘OK, maybe this is financially worthwhile,’” says McGough. “Whereas previously, they thought that they didn’t utilize that much health care, so it wasn’t worth it to purchase health care on the marketplaces.”

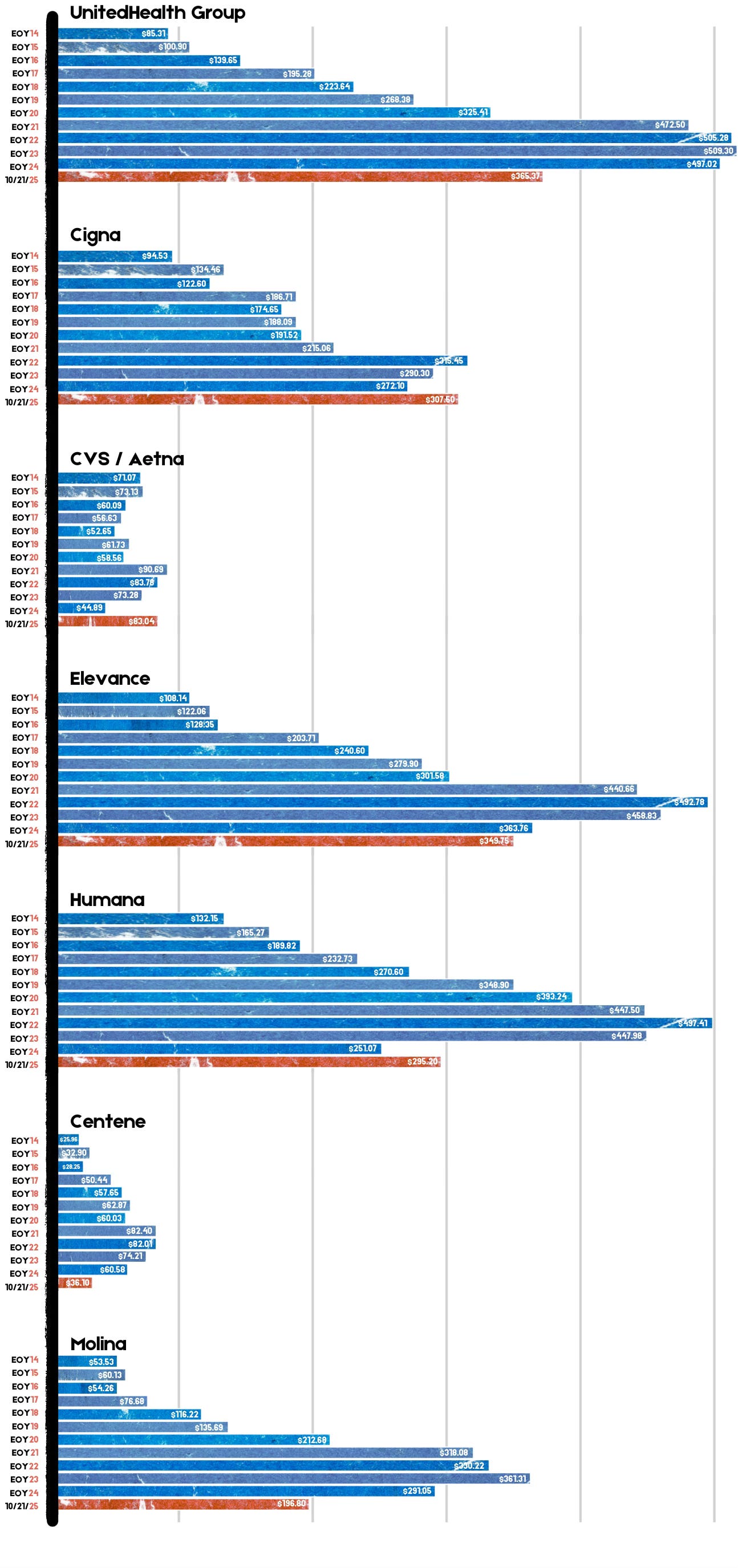

Why insurers want to increase rates

Every year, health insurers submit filings to state regulators that detail how much they need to change rates for their ACA-regulated health plans. KFF analyzed 312 insurers across 50 states and the District of Columbia; they found that insurers are requesting the largest rate changes since 2018.

They are requesting the median 18% increase for a few reasons, including rising health care costs, tariffs, and the expiration of the premium tax credit enhancements, KFF found. Health care costs have been rising for years, but insurers say that the cost of medical care is up about 8% from last year. They say that tariffs may put upward pressure on the costs of pharmaceuticals and that growing demand for GLP-1 drugs such as Ozempic and Wegovy is driving up their expenses.

Worker shortages are also driving health care costs up, according to the KFF analysis. It also found that consolidation among health care providers was leading to higher prices because those providers had more market power.

Everyone’s bottom line could be affected

When they went into effect, the enhanced premium tax credits pushed some people into the marketplace who might otherwise have been uncertain about whether to get health insurance. The tax credits were graduated so that people with the lowest incomes got the most help, but they also reached people with slightly higher incomes.

Many people don’t know that those enhancements to the premium tax credits are going away, says Jennifer Sullivan, director of health coverage access for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). Her organization has been talking to people across the country about how they may be affected if Congress does not extend the enhancements, and has found that even increases of $100 or $200 a month may be enough to force some people out of the marketplace.

“It’s a huge increase in anyone’s budget, particularly at a time when groceries are up and the cost of housing is up and so is everything else,” Sullivan says.

There are other reasons the ACA marketplace may see fewer enrollees, she says. A handful of policies passed by Congress require more verification to enroll in ACA plans and cut immigrant eligibility, for example.

Fewer enrollees are bad news for everyone else. The people who are likely to drop coverage are those who don’t need it for lifesaving treatment or medicine. That means the pool of people who are still covered by ACA plans will be sicker and more expensive to care for.

“The people who are left are statistically more likely to be people with higher health care needs,” says Sullivan, with CBPP. “Those are the folks that are going to jump through extra hoops, whether it’s more paperwork or higher premiums or higher out-of-pocket costs, because they absolutely know they need the coverage.”

There are other society-wide effects to people dropping their health insurance coverage. Many uninsured people end up in emergency rooms for care because that’s their only option, and sometimes, they can’t pay. That increases the cost of health care for everyone else, says Sullivan.

Amy Bielawski, 60, is one of the people who is going to look at her options when rates for marketplace plans are listed in October and decide whether or not to enroll. Bielawski, an entrepreneur and entertainer who performs belly dancing at parties, has spent much of her life without health care.

She finally signed up for an ACA plan in 2019, and was able to go to a doctor and diagnose her hypothyroidism and uterine fibroids. Last year, because of the enhanced premium tax credits, she paid $0 a month in premiums—which will almost certainly go up.

“I’m afraid, I’m very afraid,” says Bielawski, who lives in Georgia. “I can’t wrap my head around it because there are so many things that can go wrong with my health.”

Where politicians stand now

Addressing this uncertainty is one key reason the Affordable Care Act passed in the first place in 2010. It has dramatically improved health coverage for Americans; nearly 50 million people, or one in seven U.S. residents, have been covered by health insurance plans through ACA marketplaces since they first launched in late 2013.

But it has also faced numerous challenges, and Republicans have long said that weakening or revamping the law is a high priority.

It’s unclear if the hassle of a government shutdown will make them change their tune. In September, Senate Majority Leader John Thune, a Republican from South Dakota, said he was open to addressing the expiration of the subsidies, but that he did not want to tie any of those policy changes to government funding measures. Sen. Mike Rounds, also a Republican of South Dakota, has suggested a one-year extension to the subsidies, after which the tax credits return to pre-pandemic levels.

Many Republicans appear determined to end the subsidies eventually, and their insistence on scaling back spending on health care policy seems to be having an impact.

Sullivan, with the CBPP, says that the changes to the Affordable Care Act and looming cuts to Medicaid have the potential to dramatically reduce the number of people able to afford regular medical care in the country. These cuts come at a time when key indicators like infant mortality rates and life expectancy rates are worsening.

“We are seeing a real weakening of that safety net that we spent the last 10-15 years fortifying,” she says.