https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/hospitals-are-germy-noisy-places-some-acutely-ill-patients-are-getting-treated-at-home-instead/2018/03/30/5fcb5006-2155-11e8-badd-7c9f29a55815_story.html?utm_term=.e3db8d812c05

Phyllis Petruzzelli spent the week before Christmas struggling to breathe. When she went to the emergency department on Dec. 26, the doctor at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital near her home in Boston said she had pneumonia and needed hospitalization. Then the doctor proposed something that made Petruzzelli nervous. Instead of being admitted to the hospital, she could go back home and let the hospital come to her.

As a “hospital-at-home” patient, Petruzzelli learned, doctors and nurses would come to her home twice a day and perform any needed tests or bloodwork.

A wireless patch would be affixed to her skin to track her vital signs and send a steady stream of data to the hospital. If she had any questions, she could talk via video chat anytime with a nurse or doctor.

Hospitals are germy and noisy places, putting acutely ill, frail patients at risk for infection, sleeplessness and delirium, among other problems. “Your resistance is low,” Petruzzelli said the doctor told her. “If you come to the hospital, you don’t know what might happen. You’re a perfect candidate for this.”

So Petruzzelli, who is now 71, agreed. That afternoon, she arrived home in a hospital vehicle. A doctor and nurse were waiting at the front door. She settled on the couch in the living room, with her husband, Augie, and dog, Max, nearby. The doctor and nurse checked her IV, attached the monitoring patch to her chest, and left.

When David Levine, the doctor, arrived the next morning, he asked Petruzzelli why she had been walking around during the night. Far from feeling uncomfortable that her nocturnal trips to the bathroom were being monitored, “I felt very safe and secure,” Petruzzelli said. “What if I fell while my husband was out getting me food? They’d know.”

After three uneventful days, she was “discharged” from her hospital-at-home stay. “I’d do it again in a heartbeat,” Petruzzelli said.

Brigham Health is one of a slowly growing number of health systems that encourage selected acutely ill emergency department patients to opt for hospital-level care at home.

In the couple of years since Brigham Health started testing this type of care, hospital staff who were initially skeptical have generally embraced it, Levine said. “They very quickly realize that this is really what patients want, and it’s really good care.”

This approach is quite common in Australia, Britain and Canada, but it has faced an uphill battle in the United States.

A key obstacle, clinicians and policy analysts agree, is getting health insurers to pay for it. At Brigham Health, the hospital can charge an insurer for a physician house call, but the remainder of the hospital-at-home services are covered by grants and other funding, Levine said.

Insurers don’t have a position on hospital-at-home programs, said Cathryn Donaldson, a spokeswoman for America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade group.

“Overall, health insurance providers are committed to ensuring patients have access to care they need, and there are Medicare Advantage plans that do cover this type of at-home care,” Donaldson said in a statement.

Levine, a clinician-investigator at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an instructor at Harvard Medical School, was the lead author of a recently published study comparing patients who received either hospital-level care at home or in the hospital in 2016.

The 20 patients analyzed in the trial had one of several conditions, including infection, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. The trial found that while there were no adverse events in the home-care patients, their treatment costs were significantly lower — about half that of patients treated in the hospital.

Why? For starters, labor costs for at-home patients are lower than for patients in a hospital, where staff must be on hand around the clock. Home-care patients also had fewer lab tests and visits from specialists.

The study found that both groups of patients were about equally satisfied with their care, but the home-care group was more physically active.

Brigham Health is conducting further randomized controlled trials to test the at-home model for a broader range of diagnoses.

Bruce Leff began exploring the hospital-at-home concept more than 20 years ago, conducting studies that found fewer complications, better outcomes and lower costs in home-care patients.

Hospitals, accustomed to the traditional business model that emphasizes filling hospital beds in a bricks-and-mortar facility, have been slow to embrace the idea, however.

There are practical hurdles, too.

“It’s still easier to get Chinese food delivered in New York City than to get oxygen delivered at home,” said Leff, a professor of medicine and director of Johns Hopkins Medical School’s Center for Transformative Geriatric Research.

Since the seven-hospital Mount Sinai system in New York launched its hospital-at-home program, more than 700 patients have chosen it. And they have fared well on a number of measures.

The average length of stay for acute care was 5.3 days in the hospital vs. 3.1 days for home-care patients, while 30-day readmission rates for home-based patients were about half of those who had been hospitalized: 7.8 percent vs. 16.3 percent.

Begun with a $9.6 million federal grant in 2014, Mount Sinai’s program initially focused on Medicare patients with six conditions, including congestive heart failure, pneumonia and diabetes. Since then, the program has expanded to include dozens of conditions, including asthma, high blood pressure and serious infections such as cellulitis, and is now available to some privately insured and Medicaid patients.

Mount Sinai has also partnered with Contessa Health, a company with expertise in home care, to negotiate contracts with insurers to pay for hospital-at-home services.

Among other things, insurers are worried about the slippery slope of what it means to be hospitalized, said Linda DeCherrie, clinical director of the mobile acute care team at Mount Sinai.

Insurers “don’t want to be paying for an admission if this patient really wouldn’t have been hospitalized in the first place,” DeCherrie said.

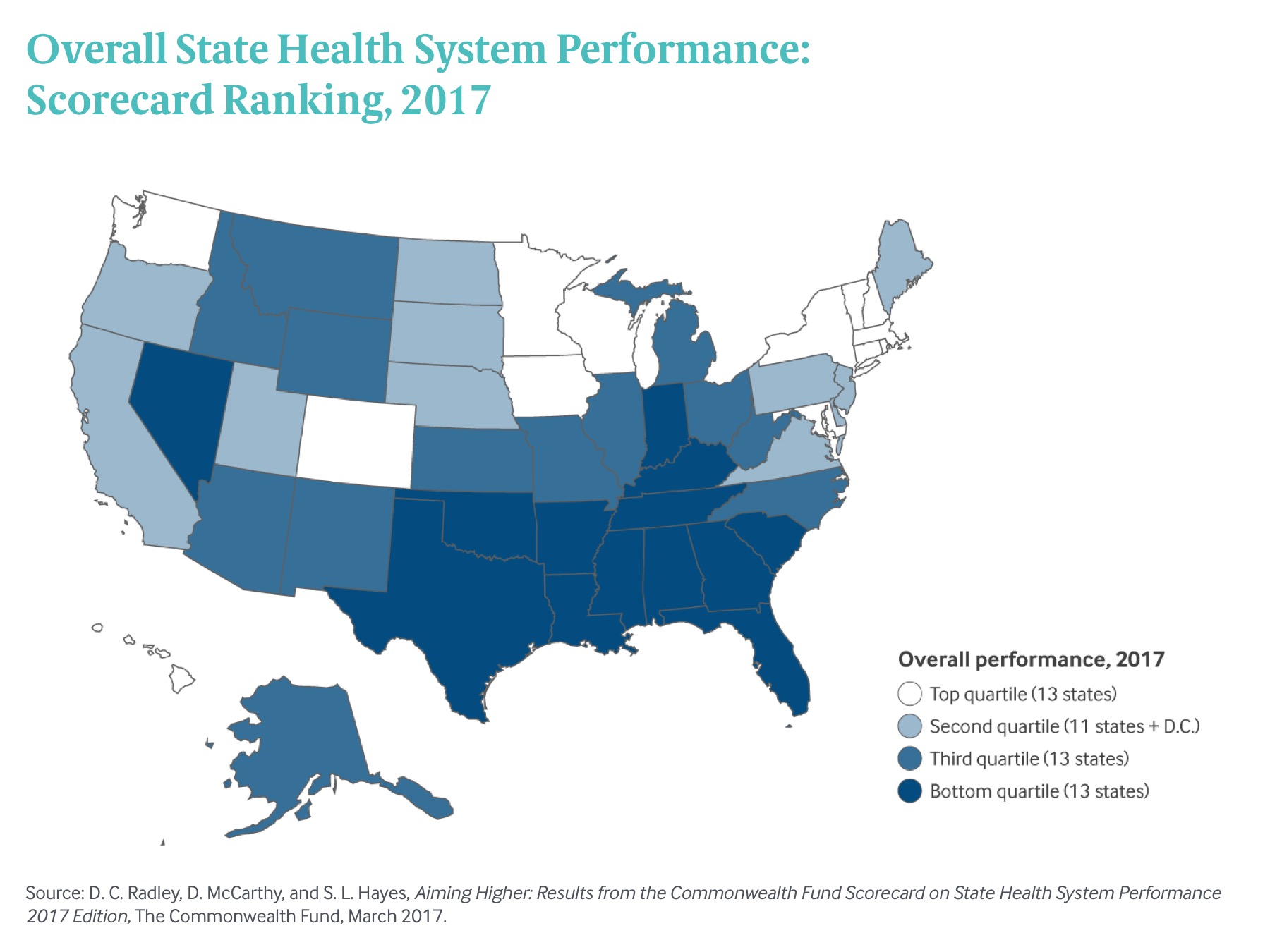

Exhibit 1: Overall State Health System Performance: Scorecard Ranking, 2017

Exhibit 1: Overall State Health System Performance: Scorecard Ranking, 2017