A small but increasing number of children in the United States are not getting some or all of their recommended vaccinations. The percentage of children under 2 years old who haven’t received any vaccinations has quadrupled in the last 17 years, according to federal health data released Thursday.

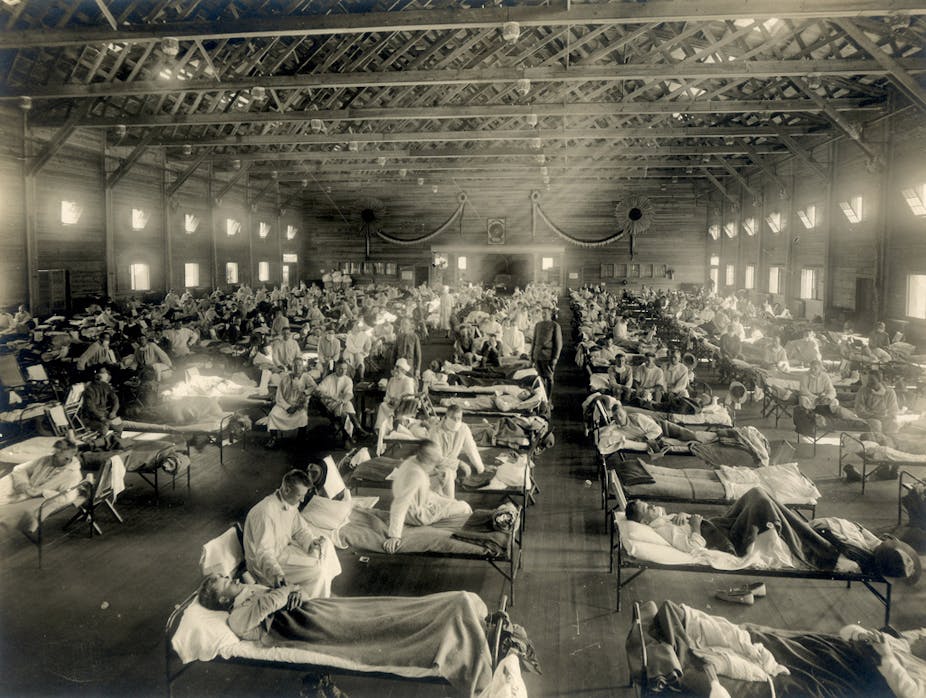

Overall, immunization rates remain high and haven’t changed much at the national level. But a pair of reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about immunizations for preschoolers and kindergartners highlights a growing concern among health officials and clinicians about children who aren’t getting the necessary protection against vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles, whooping cough and other pediatric infectious diseases.

The vast majority of parents across the country vaccinate their children and follow recommended schedules for this basic preventive practice. But the recent upswing in vaccine skepticism and outright refusal to vaccinate has spawned communities of undervaccinated children who are more susceptible to disease and pose health risks to the broader public.

Of children born in 2015, 1.3 percent had not received any of the recommended vaccinations, according to a CDC analysis of a national 2017 immunization survey. That compared with 0.9 percent in 2011 and with 0.3 percent of 19- to 35-month-olds who had not received any immunizations when surveyed in 2001. Assuming the same proportion of children born in 2016 didn’t get any vaccinations, about 100,000 children who are now younger than 2 aren’t vaccinated against 14 potentially serious illnesses, said Amanda Cohn, a pediatrician and CDC’s senior adviser for vaccines. Even though that figure is a tiny fraction of the estimated 8 million children born in the last two years who are getting vaccinated, the trend has officials worried.

“This is something we’re definitely concerned about,” Cohn said. “We know there are parents who choose not to vaccinate their kids . . . there may be parents who want to and aren’t able to” get their children immunized.

Some diseases, like measles, have made a return in the United States because parents in some areas have failed or chosen not to vaccinate their children. Last year, Minnesota suffered a measles outbreak, the state’s worst in decades. It was sparked by anti-vaccine activists who targeted an immigrant community, spreading misinformation about the measles vaccine. Most of the 75 confirmed cases were young, unvaccinated Somali American children.

The data underlying the latest reports do not explain the reason for the increase in unvaccinated children. In some cases, parents hesitate or refuse to immunize, officials and experts said. Insurance coverage and an urban-rural disparity are likely other reasons for the troubling rise.

Among children aged 19 months to 35 months in rural areas, about 2 percent received no vaccinations in 2017. That is double the number of unvaccinated children living in urban areas.

The new data shows health insurance plays a significant role, as well. About 7 percent of uninsured children in this age group were not vaccinated in 2017, compared with 0.8 percent of privately insured children and 1 percent of those covered by Medicaid.

Those differences are concerning because uninsured and Medicaid-insured children are eligible for free immunizations under the federally funded Vaccines for Children program.

“Parents may not be aware of this, so this may be an education issue,” Cohn said.

Other issues, such as child care, transportation and a shortage of pediatricians in rural areas, are also likely to affect vaccination coverage.

A second report on vaccination coverage for children entering kindergarten in 2017 also showed a gradual increase in the percentage who were exempted from immunization requirements. (The exemptions do not distinguish between one vaccine versus all vaccines.)

Eighteen states allow parents to opt their children out of school immunization requirements for nonmedical reasons, with exemptions for religious or philosophical beliefs.

The overall percentage of children with an exemption was low, 2.2 percent. But the report noted “this was the third consecutive school year that a slight increase was observed.” The report does not provide a breakdown, but the majority of exemptions are nonmedical, according to data reported by the states.

Saad Omer, a professor of global health, epidemiology and pediatrics at Emory University, said that an analysis he and colleagues conducted a few years ago found the rate of increase in nonmedical exemptions had appeared to stabilize by the 2015-2016 school year after many years of increase.

But the latest CDC data appears to reflect a change, he said. “It seems that in recent years, exemptions are going up, and the trend is likely due to parents refusing to vaccinate,” he said.

In the 2017-2018 school year, 2.2 percent of U.S. kindergartners were exempted from one or more vaccines, up from 2 percent in the 2016-2017 school year, and from 1.9 percent in the 2015-2016 school year, according to the CDC report.

Reasons for the increase couldn’t be determined from the data reported to CDC, the agency said. But researchers said factors could include the ease of obtaining exemptions or parents’ hesitancy or refusal to vaccinate.

States such as West Virginia and Mississippi, which do not allow nonmedical vaccine exemptions, have higher percentages of children getting vaccinated, said Mobeen Rathore, a pediatric infectious disease physician in Jacksonville, Fla., and a spokesman for the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

Earlier this year, researchers from several Texas academic centers identified “hotspots” where outbreak risk is rising in 12 of the 18 states that allow nonmedical exemptions because a growing number of kindergartners have not been vaccinated.