https://mailchi.mp/325cd862d7a7/the-weekly-gist-march-13-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

|

|

|

https://mailchi.mp/325cd862d7a7/the-weekly-gist-march-13-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

|

|

|

https://mailchi.mp/325cd862d7a7/the-weekly-gist-march-13-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

President Trump declared a national emergency today, in response to the growing spread of coronavirus across the country. The administration had come under sharp criticism for its sluggish response to the coronavirus crisis, in particular the widespread shortage of tests. Dr. Antony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Health’s infectious disease branch, told Congress on Thursday that the government’s response on testing was “not really geared to what we need right now…That’s a failing. Let’s admit it.”

In response, the administration today announced a series of emergency steps to increase testing capacity, turning to private labs to support the effort. The emergency status frees up $50B in federal emergency funding. Trump also announced that the Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary will be able to waive regulations around telemedicine licensing, critical access hospital bed requirements and length of stay, and other measures to provide hospitals with added flexibility. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin have negotiated a sweeping aid package that would strengthen safety net programs, and offer sick leave for American workers affected by the virus.

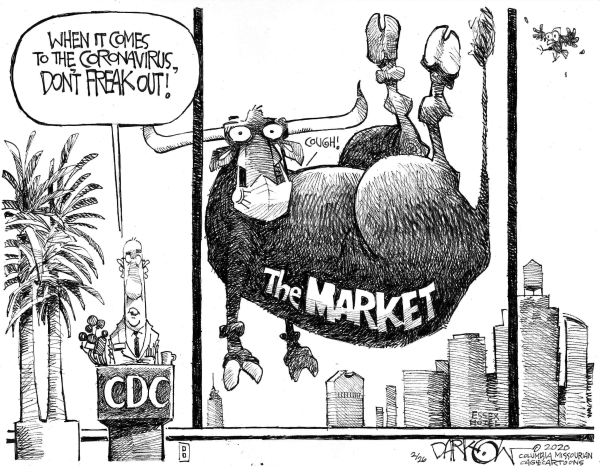

Meanwhile, the American economy likely entered a recession, as consumers continued to pull back on spending on airline travel, entertainment, and other discretionary areas, while financial markets experienced the worst one-day drop in more than 30 years. Many school districts and universities shut down and announced plans to convert to online instruction for the foreseeable future. Employers imposed broad travel restrictions on their employees, moved to teleworking where possible, and even began to lay off workers as demand for services cratered. Shoppers stocked up on staples, cleaning supplies, and (inexplicably) toilet paper, as shelves ran bare in many stores.

Epidemiologists and disease experts urged broad adoption of “social distancing”, restricting large gatherings and reducing the ability of the virus to spread person-to-person. The objective: “flattening the curve” of transmission, so that the healthcare delivery system does not become overwhelmed as the virus spreads exponentially.

For those severely ill with a respiratory disease such as covid-19, ventilators are a matter of life or death because they allow patients to breathe when they cannot on their own.

In a report last month, the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins estimated America has a total of 160,000 ventilators available for patient care (with at least an additional 8,900 in the national stockpile).

A planning study run by the federal government in 2005 estimated that if America were struck with a moderate pandemic like the 1957 influenza, the country would need more than 64,000 ventilators. If we were struck with a severe pandemic like the 1918 Spanish flu, we would need more than 740,000 ventilators — many times more than are available.

The United States has roughly 2.8 hospital beds per 1,000 people. South Korea, which has seen success mitigating its large outbreak, has more than 12 hospital beds per 1,000 people. China, where hospitals in Hubei were quickly overrun, has 4.3 beds per 1,000 people. Italy, a developed country with a reasonably decent health system, has seen its hospitals overwhelmed and has 3.2 beds per 1,000 people.

The United States has an estimated 924,100 hospital beds, according to a 2018 American Hospital Association survey, but many are already occupied by patients at any one time. And the United States has 46,800 to 64,000 medical intensive-care unit (ICU) beds, according to the AHA. (There are an additional 51,000 ICU beds specialized for cardiology, pediatrics, neonatal, burn patients and others.)

A moderate pandemic would mean 1 million people needing hospitalization and 200,000 needing intensive care, according to a Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security report last month. A severe pandemic would mean 9.6 million hospitalizations and 2.9 million people needing intensive care.

Now, factor in how stretched-thin U.S. hospitals already are during a normal, coronavirus-free week handling usual illnesses: patients with cancer and chronic diseases, those walking in with blunt-force trauma, suicide attempts and assaults. It’s easy to see why experts are warning that if the pandemic spreads too widely, clinicians could be forced to ration care and choose which patients to save.

This is where we need to say that no one knows how bad this is going to get. But, as many experts have pointed out, that is part of the problem.

“The problem with forecasting is you have to know where you are before you know where you’re going and because of the problems with testing, we’re only starting to know where we are,” said Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

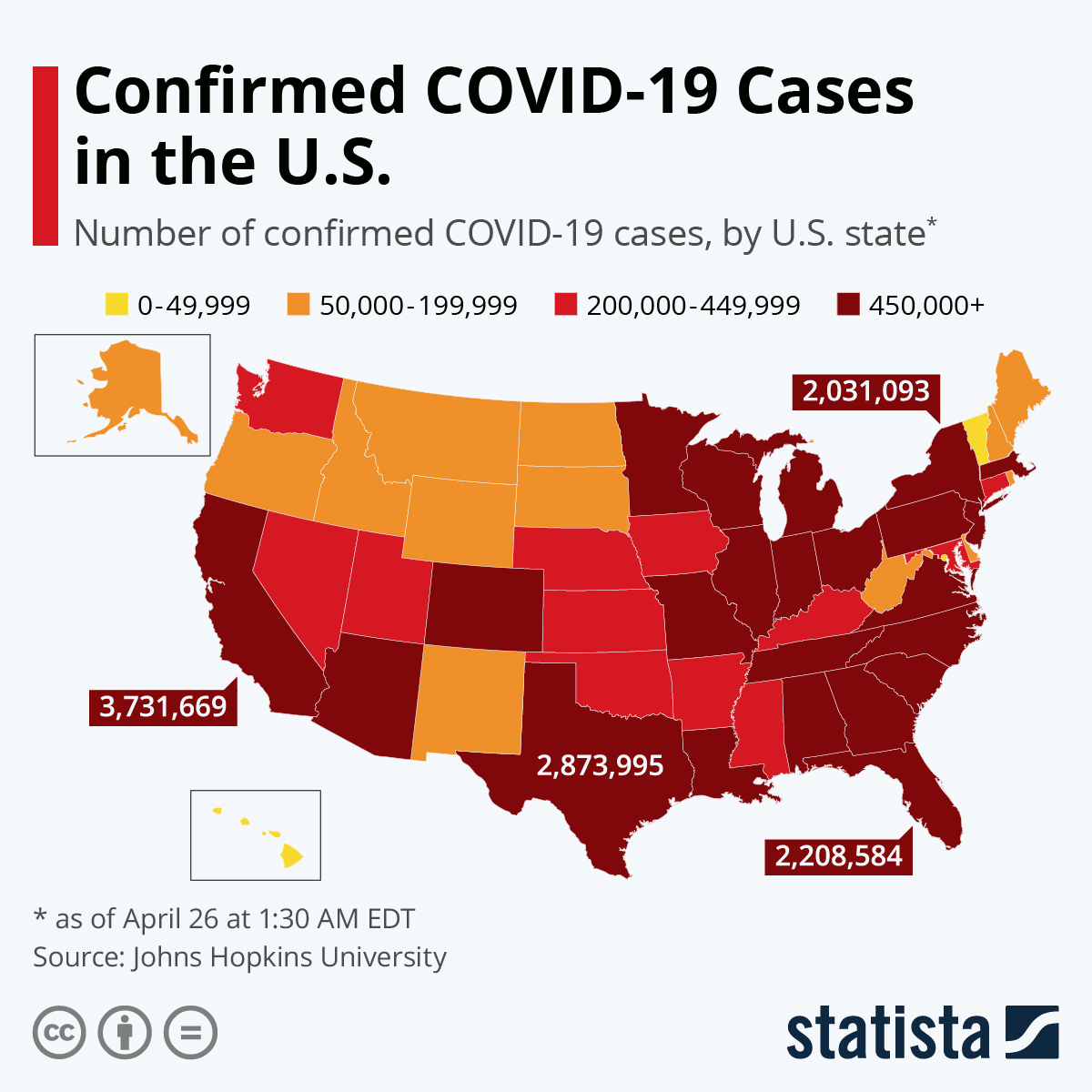

The speed at which the number of U.S. cases is rising hints we are headed in a bad direction.

But because so much is still unknown, exactly how bad could range widely. It will depend largely on two things: The number of Americans who end up getting infected and the virus’s still-unknown lethality (its case-fatality rate).

One forecast, developed by former CDC director Tom Frieden, found that infections and deaths in the United States could range widely. In a worst-case scenario, but one that is not implausible, half the U.S. population would get infected and more than 1 million people would die. But his model’s results varied widely from 327 deaths (best case) to 1,635,000 (worst case) over the next two or three years.

“Slowing it down matters because it prevents the health service becoming overburdened,” said Bill Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “We have a limited number of beds; we have a limited number of ventilators; we have a limited number of all the things that are part of supportive care that the most severely affected people will require.”

The sooner you interrupt the virus’s chain of transmission, experts say, the more you limit its climb toward exponential growth. It’s similar to the compounding interest behind all those mottos about invest when you’re young. Early action can have profound effects.

That math is also why so many health officials, epidemiologists and experts have expressed frustration, anger and alarm over how slowly America as a country has moved and is still moving to prepare for the virus and to blunt its spread.

In less than three months, the novel coronavirus has spread from an unknown pathogen located in a single Chinese city to a global phenomenon that is affecting nearly every part of society.

U.S. stocks closed more than 7% lower on Monday, after a wild day that saw a rare halt in trading, Axios’ Courtenay Brown reports.

Italy’s prime minister announced that the government has extended internal travel restrictions to the entire country until April 3 and that all public gatherings and sporting events would be banned.

Hospitals are reporting that their supplies of critical respirator masks are quickly dwindling, the New York Times reports.

At this writing, the number of COVID-19 cases worldwide has reached 100,000 with 3,500 deaths. These numbers will be higher by tomorrow.

What does this have to do with U.S. healthcare reform? A lot.

Two current background articles drive home the point that a well-functioning public health system is critical for responding to a pandemic like 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), especially in its early phases. And it means that the healthcare system – including a robust public health infrastructure — should be about health, not just about profit and greed.

Let’s Put This in Context: Is COVID-19 “Just Another Flu”?

WHO reports that annual cases of influenza A and B worldwide range from 3 to 5 million, causing 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths. That’s a lot more than COVID-19, at least so far. So what’s the big deal?

The big deal is that, This Is Not a Competition, not an either-or between influenza virus and coronavirus. Otherwise this would be like asking, Would you rather be killed by an airplane crash, by tobacco-related cancer, or by pollution-related pneumonia? The answer is, of course, none of the above.

What these types of deaths and illness have in common is being in part preventable by known public health measures, with different interventions needed for each one. Likewise, influenza A and B deaths are in part preventable. Prevention relies on the elaborate and sophisticated worldwide influenza vaccine program. It includes monitoring influenza strains alternating between Northern and Southern hemispheres, annual adjustment of vaccine components, production, distribution, and public messaging.

But unlike influenza, currently COVID-19 is not preventable, since vaccine development and testing will take a year or more. And WHO is modeling that COVID-19 is at best only partially containable by general non-pharmaceutical measures. For example, one worst-case model of the pandemic estimates that two-thirds of the world’s population could be infected, once it runs its course. This has epidemiologists scrambling to calculate the actual transmissibility and actual mortality rates so as to refine predictions more accurately and to help plans for mitigating its spread.

So, no, COVID-19 is not “just another flu,” as the President implied in a March 4 off-the-cuff interview. COVID-19 is to be sure, a “flu-like illness,” but it has unique (as yet not fully characterized) epidemiologic characteristics, and it requires a completely different public health strategy, at least in the short- and medium-term. The President is reckless to minimize either disease – both diseases are widespread and lethal — especially since proper public messaging is a key to rallying a coherent response by individuals, communities, and nations.

How Bad Could It Be? Comparison to 1918 Spanish Flu

Could the COVID-19 pandemic wreak the same devastation as the 1918 Spanish flu? Spanish flu eventually infected 500 million people worldwide, effectively 25 percent of the total global population. And it killed up to 100 million of them. “It left its mark on world history,” according to University of Melbourne professor James McCaw, a disease expert who mathematically modelled the biology and transmission of the disease, and who was quoted today by the Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC).

What SARS-CoV2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-corona virus strain 2), the agent that causes COVID-19 disease, has in common with the H1N1/Spain agent is novelty, transmissibility, and lethality. Novelty means that it is antigenically new, so that no one in the world is already immune or even partially cross-immune. Transmissibility means it’s easily spread by aerosol (coughing) or surface contact (hand to nose). Lethality means its significant death rate.

On the one hand, Dr. McCaw hopes that public health measures against COVID-19 will be more effective than in 1918. For one, experts and the general public now know about viruses. In 1918, virology was in its infancy.

“We’re not going to see that sort of level of mortality, that mortality was driven by the social context of the outbreak,” predicts Dr. Kirsty Short, a University of Queensland virologist, also quoted by the ABC. “We had a viral outbreak, at the same time as the end of a world war.”

In addition, modern medicine means much better care is available now than it was then. “We’ve already got a lot of scientists working on novel therapies and novel vaccines to try to protect the general population,” Dr Short says.

Professor McCaw points to an apparent initial success in Wuhan Province. “What’s happened in China gives very clear evidence that we can get what’s called the ‘reproduction number’ under one. So at the moment in China, on average, each person infected with coronavirus is passing that infection on to fewer than one other person. If people hadn’t changed their behaviour, we would have expected somewhere around the millions of cases in China by now instead of the comparatively small number of around 100,000.” So, he says, it looks like the transmissibility of coronavirus can be significantly modified through social distancing and good hygiene.

On the other hand, best-case calculations from these Australian epidemiologists appear to discount other factors that could actually worsen the pandemic in 2020 compared with 1918 – rapid international travel and higher concentration of people in urban centers.

Both Dr. Short and Professor McCaw admit that in the early days of a pandemic accurate predictions remain difficult to make.

Nevertheless, they both make clear that in battling the coronavirus, the national and international public health systems – and the public’s trust in them – will be key.

Public Health Approach Is the Key

The importance of public health actions is underscored by a second report today by two experts from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank.

Samuel Brannen and Kathleen Hicks write in Politico.com,

Last October, we convened a group of experts to work through what would happen if a global pandemic suddenly hit the world’s population. The disease at the heart of our scenario was a novel and highly transmissible coronavirus. For our fictional pandemic, we assembled about 20 experts in global health, the biosciences, national security, emergency response and economics at our Washington, D.C., headquarters. The session was designed to stress-test U.S. approaches to global health challenges that could affect national security. As specialists in national security strategic planning, we’ve advised U.S. Cabinet officials, members of Congress, CEOs and other leaders on how to plan for crises before they strike, using realistic but fictional scenarios like this one.

Here are their conclusions:

Healthcare Reform: We’re All in This Together

The impending epidemic of coronavirus in the U.S. also brings up important practical questions in the whole healthcare system, as reported in, for example, the New York Times and Kaiser Family Foundation.

Who will have access to testing? Who will pay? Will copays designed to keep patients with trivial illnesses from overutilizing the health system now backfire by delaying their testing and care? These kinds of questions are not at issue in countries with universal access.

However, even those countries will struggle to cope with the pandemic. For example, the United Kingdom faces a shortage of intensive care unit beds after a decade of downsizing its bed capacity.

This drives home the point that public health infrastructure is necessary but not sufficient for managing a pandemic. Namely, the U.K.’s bed shortage shows that public health is but one component of the broader task of maintaining a nation’s strategic risk preparedness. Calculating the surge capacity of inpatient beds for an unexpected pandemic emergency should not be left just to hospital administrators. This is also why the President should restore both bio-preparedness positions dropped by him in 2018 from the National Security Council and the Homeland Security Department.

Conclusion: Right, Privilege or, Rather, Social Contract?

Is healthcare a right or a privilege? The coronavirus tells us, Neither. Instead, this virus reminds us that healthcare is better framed as part of the social contract, the fundamental duty of governments to their citizens to defend them from clear threats, both currently present and foreseeable, not only military, but also economic, cyber, and in this case biological. Can Americans and their leaders put aside petty polemical bickering over healthcare reform and recognize the healthcare system for what it is, part of the backbone of a healthy, resilient nation?

https://mailchi.mp/9e118141a707/the-weekly-gist-march-6-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

As of Friday, the number of confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus, or COVID-19, has surpassed 100,000 worldwide, with over 3,400 deaths. In the US, there have been 250 confirmed cases and 14 deaths reported so far—although the actual number of cases is certainly many times higher, with testing yet to be widely available and many patients exhibiting only mild to moderate symptoms.

Vice President Mike Pence, who was put in charge of federal response efforts last week, conceded Thursday that the country does not yet have enough coronavirus tests to meet demand, and the administration will not meet its goal of having 1M tests ready by the end of the week; perhaps the $8B emergency funding package approved by Congress will help expedite efforts.

Public worry and concern among officials hit new levels, with the Director-General of the World Health Organization warning that time to contain the virus may be running out, and expressing concern that countries may not be acting fast enough. New levels of containment effort have begun to take shape. Schools shut down in areas of the country most affected by the virus, including Seattle and some New York City suburbs. All told, the New York Times reports that 300M students are out of school around the world. Companies began to cancel conferences and other large gatherings—next week’s Health Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) conference was called off despite a planned appearance by President Trump, given rising cancellations and vendor exits.

Hospitals around the nation have rallied to prepare for a growing wave of patients that has yet to hit. Experts expressed concerns about whether hospitals have enough open capacity, but even more critical will be gaps in the supply of staff and equipment—especially the ICU beds and ventilators necessary for critically ill patients, and the nurses and respiratory therapists needed to care for them.

The vast majority of hospitals report having a coronavirus action plan in place; however, a recent survey of nurses suggests that critical information may not be making its way to frontline clinicians. Only 44 percent of nurses reported that their organization gave them information on how to identify patients with the virus, and just 29 percent said there is a plan in place to isolate potentially infected patients.

Worries about patient financial exposure to the costs of diagnosis and treatment intensified, with fears that individuals could be held accountable for the cost of government-mandated isolation. Most patients with high-deductible plans saw their deductibles “reset” at the beginning of the year, raising concerns that individuals might refrain from seeking treatment.

The heightened worry is palpable as we connect with hospital and physician leaders around the country, and we are deeply grateful for their around-the-clock efforts, and the willingness of doctors, nurses and other caregivers to put their own safety at risk to provide the best possible care to patients under increasingly difficult circumstances.

Congress is expected to pass a major $8.3 billion spending package to help providers and local governments handle the spread of the coronavirus and to boost the development of vaccines and tests of the virus.

Here are key parts of the spending package released Wednesday:

The package sailed through the House on Wednesday and could be taken up quickly by the Senate.

Provider groups bracing for a coronavirus outbreak praised the spending package.

“This bill will provide essential assistance to caregivers and communities on the front lines of this battle,” said Chip Kahn, president and CEO of the Federation of American Hospitals, in a statement.