https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/07/31/if-us-economy-is-good-shape-why-is-federal-reserve-cutting-interest-rates/?utm_term=.1346fb3da080&wpisrc=nl_most&wpmm=1

Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell speaks during a Senate Banking Committee hearing on July 11.

The Federal Reserve is all but certain Wednesday to do something it hasn’t done in more than a decade: cut interest rates. The question on a lot of people’s minds is why.

Lowering interest rates, the Fed’s main way to boost the economy, is typically used in dire times, which it’s difficult to argue the United States is experiencing right now. Instead, top Fed officials are defending this as an “insurance cut” that’s akin to an immunization shot in the arm. They want to counteract the negative effects of President Trump’s trade war and prevent the United States from catching the same cold that Europe, China and elsewhere seem to have.

The Fed’s big decision comes at 2 p.m. Wednesday and will be followed by a 2:30 p.m. news conference from Fed Chair Jerome H. Powell, a frequent target of Trump’s criticism.

The Fed is widely expected to do a modest cut on Wednesday, probably lowering the benchmark interest rate from about 2.5 percent down to just shy of 2.25 percent. But the Fed seldom does just one cut, which is why Trump, Wall Street and much of the world will be listening closely to Powell for signs of when another cut is likely.

Wall Street is pricing in that the Fed will lower interest rates to about 1.75 by the end of the year, a far more dramatic move. And Trump has been blasting the Fed for months, saying he wants to see a “large” cut.

“The Fed is often wrong,” Trump said this week, reiterating his view that the stock market would be up 10,000 more points if the Fed had not raised interest rates four times last year. “I’m very disappointed in the Fed. I think they acted too quickly, by far. I think I’ve been proven right.”

But there are plenty of economists and prominent investors saying the Fed shouldn’t cut at all because it is not justified and will look as though the Fed is caving in to Trump’s bullying — or Wall Street’s.

“I have to conclude the Fed has lost some independence here,” said Blu Putnam, chief economist at CME Group.

The last time the Fed cut rates was in December 2008, when unemployment was over 7 percent (and rising quickly), the stock market had lost a third of its value, and a major financial institution, Lehman Brothers, had just declared bankruptcy, rocking the financial system.

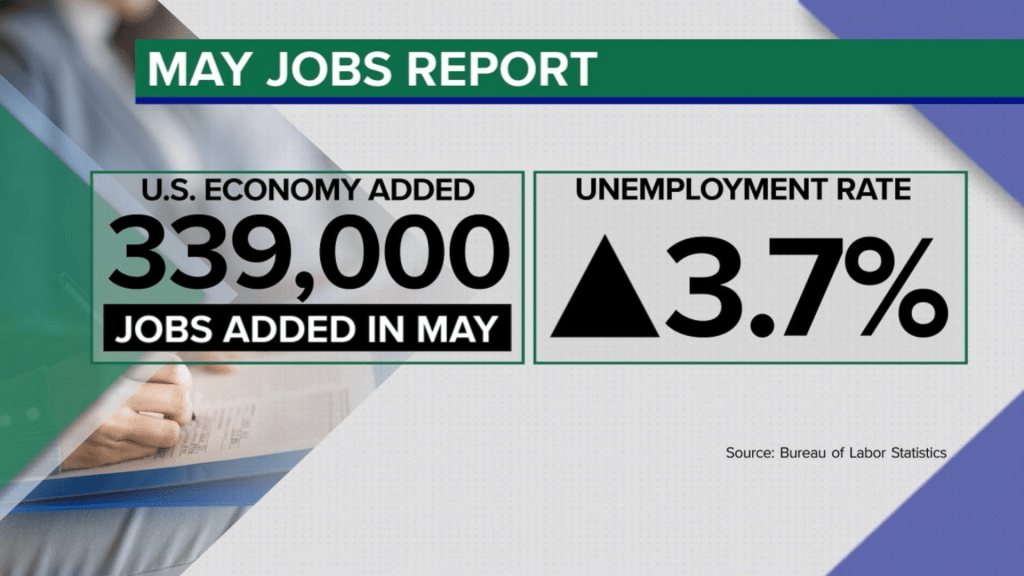

Today unemployment is at a half-century low (3.7 percent), the economy is growing at a healthy pace (over 2 percent) and the stock market is sitting at record highs.

Congress gave the Fed two mandates: to keep unemployment low and prices stable. By about any measure one can look at, the Fed has achieved those goals. The job market is strong, and inflation remains surprisingly low.

The world will be listening closely for Powell’s rationale for lowering rates during fairly good economic times — and for his signal about whether another cut is coming in the fall.

It’s a tricky calculus. The one thing nearly everyone agrees on is this would be the biggest gamble yet for Powell, who took over as the central bank’s chair in early 2018.

The likely cut on Wednesday should make loans a little cheaper for businesses and Americans looking to buy homes and cars or start a company. But realistically, one cut won’t do much. The reason the stock market has rallied sharply in recent weeks is an expectation that this is the first of several cuts.

If the Fed does not do three cuts this year, the market could pull back, making financial conditions “tight” again, even though the Fed is cutting rates to try to loosen conditions.

Top Federal Reserve leaders see three key reasons to cut now.

1. Trump’s trade war. There is concern about the trade war, as well as weakness overseas, dragging down the U.S. economy. A closer look at the U.S. economy reveals there are already a few yellow, if not red, flags. Manufacturing was in a “technical recession” the first half of the year, the housing market remains sluggish, and business investment tanked in the spring as corporate leaders grow more wary of the ongoing trade tensions.

Powell and Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida refer to these as “head winds” and “downside risks” that are picking up, and they prefer to address them before they grow into deeper problems. Clarida often points to 1995, when the Fed did three modest rate cuts (starting in July 1995 and ending in January 1996) that helped keep the economy growing for years to come.

2. The Fed needs to act sooner rater than later. New York Fed President John Williams, among others, has made the case that the Fed has limited medicine in the medicine cabinet to aid the economy and that it’s better to administer the pills at the first signs of trouble rather than waiting for full-blown illness when there might not be enough medicine left to make a difference. “When you only have so much stimulus at your disposal, it pays to act quickly to lower rates at the first sign of economic distress,” Williams said in a speech earlier this month.

Interest rates are very low by historical standards. For example, the benchmark rate was over 5 percent before the Fed started reducing it in 2007. Now the benchmark rate is half that amount, meaning there will be less stimulus this time around from cutting rates.

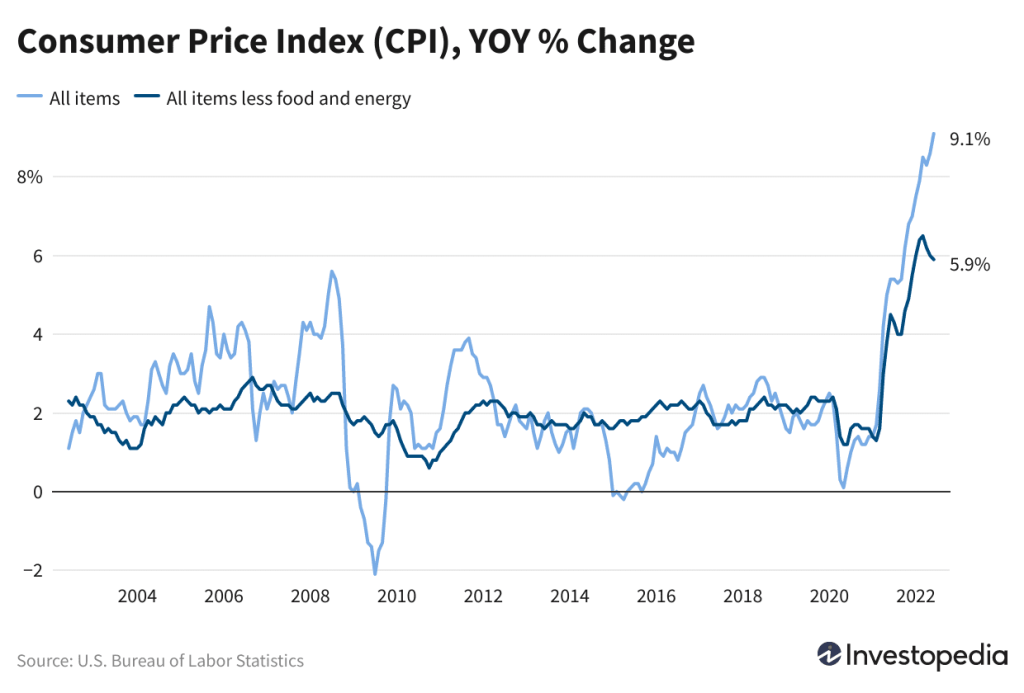

3. Inflation is too low. The Fed wants to see inflation of about 2 percent a year. For the past several years, it’s been running below that threshold and is currently sitting around 1.6 percent. Some Fed leaders, such as St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, say the Fed should cut rates to try to run the economy a bit hotter to boost inflation. They see little risk in doing this since inflation is so low, but they see great risk in not getting inflation back to target because business leaders will stop believing that 2 percent is the true target if it is never achieved.

While there are reasons to cut, some Fed leaders, including Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren and Kansas City Fed President Esther George, have raised doubts about whether it makes sense to cut now, before there are clear signs of trouble in the United States.

Rosengren has warned in recent speeches that insurance cuts do not come without a cost. Keeping rates low tends to spur bubbles that can come back to harm the economy later on. Already there are concerns about too much risky corporate lending, and lower rates are only likely to encourage more of those loans. He and others have also pointed out that using up the medicine now doesn’t leave much left to fight worse problems later on.

There are 10 members on the Fed’s committee that decides interest rate policy, and they do not appear to be in unison on this decision, let alone what to do in the fall, a reminder of just how much debate there is about the right course of action.

The U.S. economy is in the midst of a record-breaking expansion that has been growing for more than a decade, the longest expansion in U.S. history. Powell says keeping it going is his top goal.