Last week, 2 important economic reports were released that provide a retrospective and prospective assessment of the U.S. health economy:

The CBO National Health Expenditure Forecast to 2032:

“Health care spending growth is expected to outpace that of the gross domestic product (GDP) during the coming decade, resulting in a health share of GDP that reaches 19.7% by 2032 (up from 17.3% in 2022). National health expenditures are projected to have grown 7.5% in 2023, when the COVID-19 public health emergency ended. This reflects broad increases in the use of health care, which is associated with an estimated 93.1% of the population being insured that year… During 2027–32, personal health care price inflation and growth in the use of health care services and goods contribute to projected health spending that grows at a faster rate than the rest of the economy.”

The Congressional Budget Office forecast that from 2024 to 2032:

- National Health Expenditures will increase 52.6%: $5.048 trillion (17.6% of GDP) to $7,705 trillion (19.7% of GDP) based on average annual growth of: +5.2% in 2024 increasing to +5.6% in 2032

- NHE/Capita will increase 45.6%: from $15,054 in 2024 to $21,927 in 2032

- Physician services spending will increase 51.2%: from $1006.5 trillion (19.9% of NHE) to $1522.1 trillion (19.7% of total NHE)

- Hospital spending will increase 51.6%: from $1559.6 trillion (30.9% of total NHE) in 2024 to $2366.3 trillion (30.7% of total NHE) in 2032.

- Prescription drug spending will increase 57.1%: from 463.6 billion (9.2% of total NHE) to 728.5 billion (9.4% of total NHE)

- The net cost of insurance will increase 62.9%: from 328.2 billion (6.5% of total NHE) to 534.7 billion (6.9% of total NHE).

- The U.S. Population will increase 4.9%: from 334.9 million in 2024 to 351.4 million in 2032.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Report for May 2024 and Last 12 Months (May 2023-May2024):

“The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) was unchanged in May on a seasonally adjusted basis, after rising 0.3% in April… Over the last 12 months, the all-items index increased 3.3% before seasonal adjustment. More than offsetting a decline in gasoline, the index for shelter rose in May, up 0.4% for the fourth consecutive month. The index for food increased 0.1% in May. … The index for all items less food and energy rose 0.2% in May, after rising 0.3 % the preceding month… The all-items index rose 3.3% for the 12 months ending May, a smaller increase than the 3.4% increase for the 12 months ending April. The all items less food and energy index rose 3.4 % over the last 12 months. The energy index increased 3.7%for the 12 months ending May. The food index increased 2.1%over the last year.

Medical care services, which represents 6.5% of the overall CPI, increased 3.1%–lower than the overall CPI. Key elements included in this category reflect wide variance: hospital and OTC prices exceeded the overall CPI while insurance, prescription drugs and physician services were lower.

- Physicians’ services CPI (1.8% of total impact): LTM: +1.4%

- Hospital services CPI (1.0% of total impact): LTM: +7.3%

- Prescription drugs (.9% of total impact) LTM +2.4%

- Over the Counter Products (.4% of total impact) LTM 5.9%

- Health insurance (.6% of total) LTM -7.7%

Other categories of greater impact on the overall CPI than medical services are Shelter (36.1%), Commodities (18.6%), Food (13.4%), Energy (7.0%) and Transportation (6.5%).

Three key takeaways from these reports:

- The health economy is big and getting bigger. But it’s less obvious to consumers in the prices they experience than to employers, state and federal government who fund the majority of its spending. Notably, OTC products are an exception: they’re a direct OOP expense for most consumers. To consumers, especially renters and young adults hoping to purchase homes, the escalating costs of housing have considerably more impact than health prices today but directly impact on their ability to afford coverage and services. Per Redfin, mortgage rates will hover at 6-7% through next year and rents will increase 10% or more.

- Proportionate to National Health Expenditure growth, spending for hospitals and physician services will remain at current levels while spending for prescription drugs and health insurance will increase. That’s certain to increase attention to price controls and heighten tension between insurers and providers.

- There’s scant evidence the value agenda aka value-based purchases, alternative payment models et al has lowered spending nor considered significant in forecasts.

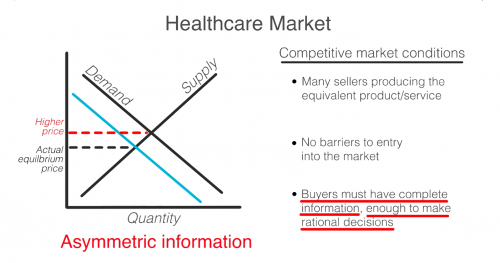

The health economy is expanding above the overall rates of population growth, overall inflation and the U.S. economy. GDP. Its long-term sustainability is in question unless monetary policies enable other industries to grow proportionately and/or taxpayers agree to pay more for its services. These data confirm its unit costs and prices are problematic.

As Campaign 2024 heats up with the economy as its key issue, promises to contain health spending, impose price controls, limit consolidation and increase competition will be prominent.

Public sector actions

will likely feature state initiatives to lower cost and spend taxpayer money more effectively.

Private sector actions

will center on employer and insurer initiatives to increase out of pocket payments for enrollees and reduce their choices of providers.

Thus, these reports paint a cautionary picture for the health economy going forward. Each sector will feel cost-containment pressure and each will claim it is responding appropriately. Some actually will.

PS: The issue of tax exemptions for not-for-profit hospitals reared itself again last week.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget—a conservative leaning think tank—issued a report arguing the exemption needs to be ended or cut. In response,

the American Hospital Association issued a testy reply claiming the report’s math misleading and motivation ill-conceived.

This issue is not going away: it requires objective analysis, fresh thinking and new voices. For a recap, see the Hospital Section below.